Input

Changed

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

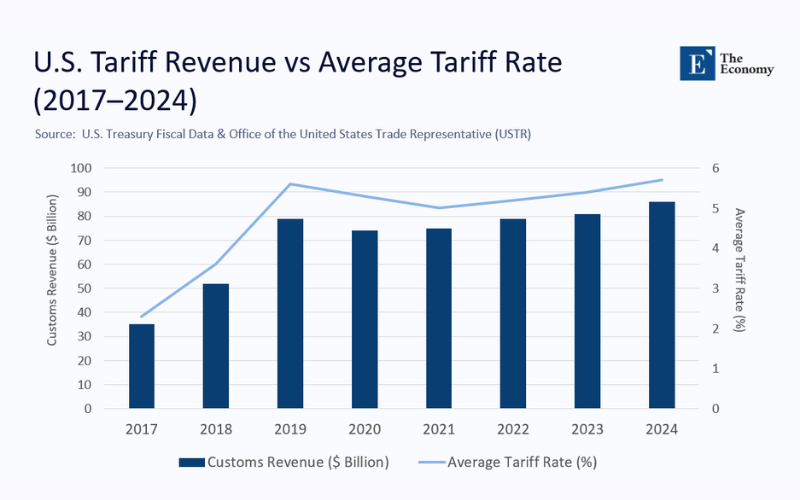

Every percentage point added to a tariff simultaneously raises the posted rate and erodes the base on which that rate is applied. The higher the levy rises, the faster the base erodes. During the most recent escalation cycle, the United States nearly quadrupled its average tariff in the space of five years, yet it collected scarcely more than it had before the first salvo was fired. That empirical contradiction is the starting point for this analysis. New evidence—from granular customs data to multi‑region computable‑general‑equilibrium simulations—confirms that tariffs are self‑throttling after surprisingly low thresholds. Any fiscal strategy that ignores this dynamic is courting arithmetic failure.

Re‑centering the Laffer Intuition on the Border

Arthur Laffer’s famous cocktail‑napkin curve was sketched initially to explain why income‑tax revenue peaks at some finite rate: push the marginal burden high enough, and the activity to be taxed begins to evaporate. Tariff Laffer curves extend the same logic to imports. The analogy, however, understates the speed of the modern adjustment process. Whereas household labor supply can take years to rearrange, software re-plots global supply chains in a matter of weeks. When tariffs jumped on Chinese consumer electronics in 2018, assembly shifted to factories in Penang and Guadalajara almost before the ink on the Federal Register filing was dry. In economists’ shorthand, U.S. import demand is elastic for most consumer goods and nearly all capital‑equipment inputs. Whenever the absolute value of that elasticity exceeds one, the revenue curve’s crest appears early—frequently before policymakers even notice that it has been passed.

Fresh Evidence and Its Implications

Recent quantitative work supplies the most precise map of that crest to date. A 2025 CEPR study by Simon Evenett and Marc-Andreas Muendler embeds the world economy in a rich general-equilibrium model and finds that tariff revenue maximizes at a uniform rate of nearly 15 percent. Above that line, production reshuffles so completely that additional rate hikes raise less cash, not more. A separate Asia Times policy note, published the same month, reaches a similar conclusion from a different starting point: empirical pass-through rates, profit-margin buffers, and currency movements restrict the realistic revenue sweet spot to the 10- to 15 percent band. And when the Tax Foundation feeds current trade elasticities into its dynamic scoring engine for Congress, the model predicts that a universal 20% tariff would generate less revenue over a ten-year horizon than a mid-teens levy once lost GDP and retaliation are taken into account. Three methodologies, three research teams, and one verdict: the United States hits diminishing returns almost as soon as tariffs leave the realm of single digits.

Elasticity in Practice Rather Than in Greek Letters

Elasticity, a concept often associated with complex mathematical symbols, is simply a measure of how easily behavior changes. Consider a popular consumer brand. When running shoes arriving from Vietnam face a twenty‑five‑percent duty, retailers do not pass the full surcharge to shoppers; instead, they source the same model from Indonesia, where no penalty applies under the current code. If that workaround proves insufficient, they discount a different brand, compressing their margins rather than losing volume altogether. Manufacturers also re-engineer products to jump tariff lines, perhaps finishing the last 5% of value in Tennessee, so that only gearboxes cross the border. Finally, exchange‑rate shifts cushion smaller duties but magnify the tariff’s impact once the buffer is spent. Each of these adjustments represents a concrete manifestation of elasticity. They explain why revenue cannot climb relentlessly with statutorily higher rates.

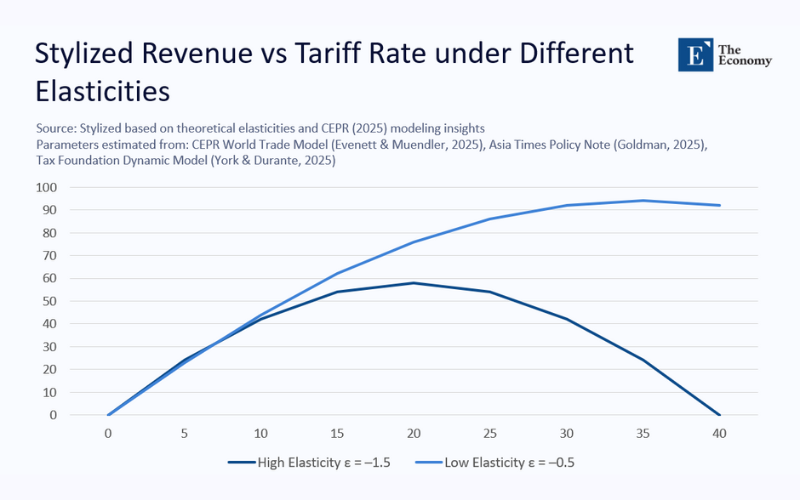

A Stylised Picture of the Curve

The accompanying chart visually summarises the mechanism. Two import‑demand schedules are plotted. The first depicts a low-elasticity world in which consumers and firms have few substitutes; revenue rises almost steadily toward a 40% tariff. The second represents the high‑elasticity reality that prevails for U.S. consumer goods; revenue peaks at roughly seventeen percent and then collapses. The post‑2018 customs data track the second trajectory with uncanny precision.

History’s Quiet Repetition

Episodes from the past century reinforce the message. The Smoot–Hawley Act of 1930, a protectionist measure that raised U.S. tariffs on over 20,000 imported goods to record levels, lifted average duties above 20 percent; yet, customs receipts plummeted as imports collapsed by 40 percent in a year. In 1981, voluntary export restraints on Japanese automobiles yielded a modest $670 million in additional collections, forcing U.S. consumers to pay $23 billion more for cars over four years. The steel and aluminum levies of 2018 recently generated a short-lived $4.6 billion gain before volumes found alternative routes and receipts stagnated. In every instance, a brief surge in revenue was followed by a plateau or outright decline—a narrative entirely consistent with the curved relationship first sketched on that napkin nearly half a century ago.

Fiscal Daydreams Meet Trade Reality

Proposals to finance vast spending programs with tariffs collapse when confronted by the Treasury’s cash ledgers. The administration’s latest claim that a universal twenty‑percent duty could bring in six hundred billion dollars annually conflicts sharply with the eighty‑six‑billion figure collected in 2024.

A mistake of an order of magnitude is evident before any behavioral response is incorporated. Moreover, tariff collections do not arrive gratis. Every extra dollar extracted at the dock crowds out sales tax, income tax, and corporate tax receipts elsewhere in the economy because higher import prices squeeze household purchasing power and business margins. Dynamic models suggest that nearly a quarter of the apparent tariff gains are offset by these secondary effects before the funds reach the Treasury vault.

The Self‑Defeating Nature of the Revenue Quest

Advocates sometimes pivot, arguing that the fundamental objective is not cash but reshoring. Reshoring refers to the process of relocating manufacturing and production jobs back to the country. Yet even if high tariffs achieve their industrial aim, they do so by erasing the import base and thus the tariff revenue itself. When a foreign automaker decides to build its next assembly plant in Alabama to dodge a border tax, the Treasury loses the duties it once levied on finished vehicles. The instrument succeeds on one axis but fails on the other.

Policy Design for a World of Elastic Imports

Pragmatism calls for a different approach. Tariffs set below fifteen percent can still provide bargaining leverage without triggering a mass flight of supply chains, particularly if the measure is temporary and escalates only when concrete, measurable trade distortions persist. For sectors of undeniable strategic importance—rare‑earth magnets or advanced lithography tools—the evidence points toward mixing modest border measures with investment subsidies rather than betting on blunt ad‑valorem walls. Any new duty should sunset after four years unless reauthorized, forcing legislators to confront real‑time data rather than operate on slogans from a bygone era. This engagement with real-time data is crucial for effective policy design in a world of elastic imports and supply chains.

The Arithmetic Sets the Boundary

The idea that tariffs might bankroll large slices of the federal budget has an intuitive surface appeal. It promises painless extraction from foreign pockets rather than domestic taxpayers. Yet elasticity flips that intuition on its head. Because the base is nimble while rates are stationary, revenue crests far below the levels imagined in stump speeches. Push the duty higher, and the base escapes faster than the tax point rises. Empirical evidence from modern customs data, historical experience dating back to the Smoot–Hawley era, and three distinct modeling traditions converge on the same practical limit: the middle teens. Beyond that, policymakers are chasing a receding horizon. They may achieve geopolitical leverage or industrial localization, but they will not harvest the funds that headline writers—and some officials—continue to promise. The uncomfortable arithmetic remains: taxation that suffocates its base cannot carry the fiscal freight, no matter how forcefully it is marketed.

The original article was authored by Simon Evenett, a Professor of Geopolitics and Strategy at IMD Business School, and Marc-Andreas Muendler, a Professor of Economics at the University of California. The English version of the article, titled "Tariffs cannot fund the government: Evidence from tariff Laffer curves,” was published by CEPR on VoxEU.