Input

Changed

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

Europe’s Hydro-Climate Paradox

Television still cuts from Alpine towns submerged in chocolate-brown torrents to Andalusian groves cracked like old porcelain, as though the two calamities belonged to separate planets. They are, in fact, manifestations of a single malfunction. The European Environment Agency calculates that weather- and climate-related extremes stripped €162 billion from the European Union in the three short years between 2021 and 2023—more than one-fifth of all such losses recorded since 1980—and it notes that each of those three years now ranks among the five costliest in the historical record. The geography is perverse: while Central Europe scrambles to open sluice gates, the Mediterranean resorts to water-tanker convoys. The pattern shows that Europe does not suffer too much or too little water on average; it suffers from water appearing in the wrong places at the wrong time. That mistiming, not meteorology, is the actual macroeconomic risk.

A Ledger Drenched in Red Ink

Greece illustrates the continental flaw in stark account-book terms. In Argolida, antiquated mains and illegal taps waste more than forty percent of drinking water, almost twice the EU average, while only eight percent of residents in the coastal town of Ermioni enjoy a secure year-round supply. Those same pipes are periodically wrecked by flash floods that now hit with such ferocity that national repair bills exceeded a billion euros in 2023 alone. Northern Europe’s disasters are grander still. When the Rhine-Meuse catchment burst its banks in July 2021, the insured and uninsured bills reached €44 billion, a single event that erased half a decade of infrastructure spending in the region and became a textbook example of how climate physics can disrupt public investment cycles overnight. Each episode shares an accounting trait: preventive hydraulics initially appear politically expensive, but hindsight reveals them to be bargains.

Irrigation, Humanity’s Oldest Growth Strategy

Two millennia ago, Qin engineers diverted Sichuan’s Min River through a split-channel system that drained lethal spring torrents and stored water for dry-season rice. The Dujiangyan weir still performs that dual function today. The ancient lesson could not be clearer: re-routing surplus water from wet periods into storage for dry months converts disaster avoidance into surplus creation. With its satellites, lidar surveys, and balance-sheet strength, Europe has no justification for persisting with a hydraulic regime that would have struck Han dynasty bureaucrats as primitive. The continent’s problem is not technical feasibility but institutional imagination.

The New Economics of Adaptation

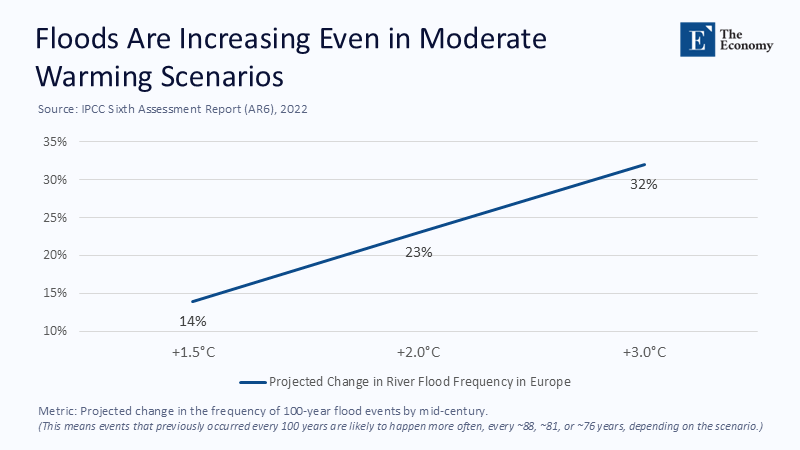

Modern econometrics now puts numbers on the intuition. A sectoral dynamic-stochastic model for England, published this year by CEPR economists, estimates that a one-percentage-point rise in annual adaptation outlays—expressed as a share of GDP—reduces the expected frequency of floods by approximately 76% after a two-year lag. At the same time, the same investment in the physical stock of pumps, levees, and diversion channels resulted in approximately thirty-three fewer flood incidents within the first year. The authors find that earlier cross-country regressions were overlooked: adaptation capital dampens core-service inflation, shields real wages, and provides monetary policy with breathing room. In other words, yearly budgets behave like insurance premiums—applicable but slow—whereas concrete, steel, and telemetry sensors operate like a supply-side stimulus with a growth multiple. That insight flips the usual austerity discourse on its head. Cutting adaptation capital expenditure is not fiscal prudence; it is a deferred sovereign liability.

The Missing Euros

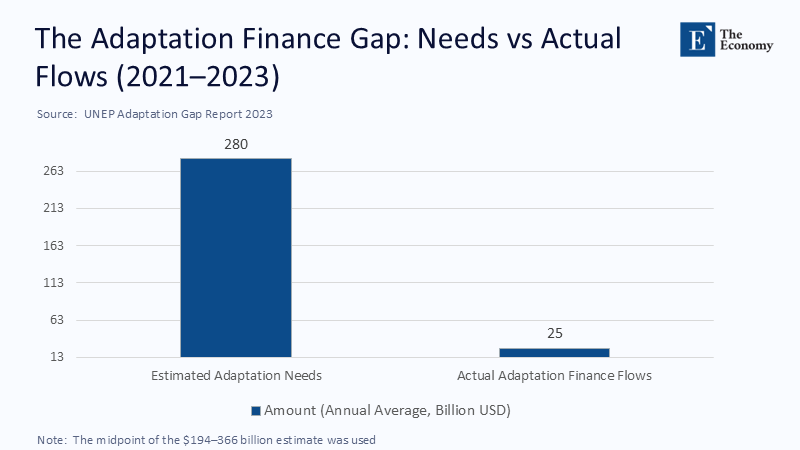

If the return on prevention is demonstrably high, why is the investment so low? The United Nations Environment Programme answers that question in its 2023 Adaptation Gap Report, which estimates annual worldwide adaptation needs at $194 billion to $366 billion, but records actual public and private flows of only $25 billion during 2017-2021. Europe’s line items track the global failure. Most member-states allocate less than 0.05% of GDP to flood defense—one-tenth of what fundamental cost-benefit analysis would prescribe once indirect supply-chain losses are included. Meanwhile, the private insurance market is retreating from catastrophe coverage; the European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority recently warned that only a quarter of hydrological losses are insured, thereby increasing the likelihood that budget-stretched governments will act as reinsurers of last resort. Fiscal orthodoxy thus produces the opposite of discipline: it socializes future disaster costs while underfunding the cheap technology that would avert those costs in the first place.

Engineering the Hydro-Backbone

The deficit is institutional, not technological. Spain already transfers 400 hm³ of water annually across the Castilian divide through the Tagus–Segura aqueduct. With its Room for the River program, the Netherlands has proved that nature-based diversions coexist with dense settlements in a delta. Norway’s hydropower tunnels join whole catchments beneath kilometre-thick granite. Europe lacks a network logic that stitches those local marvels into a continental system—a Hydro-Backbone able to bank surplus winter runoff from the north and release it during Mediterranean summers. Modeling by the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam suggests that redirecting a modest 9% of northern winter discharge southward would offset half of Iberia’s projected summer deficit by mid-century, providing a structural hedge against the precipitation gradient that climate models mark as unavoidable. The engineering portfolio would combine smart canals with low-friction pipelines and variable-level reservoirs, all rigged to provide dispatchable hydropower as a secondary benefit.

Governance Without Empires

Hydraulic states have historically degenerated into hydraulic empires, hoarding water behind upriver choke points. Today’s digital transparency allows Europe to dodge that fate. A European Water Solidarity Fund, capitalized with €50 billion of jointly issued green bonds exempt from Stability and Growth Pact ceilings, could finance backbone assets while rewarding avoided losses. Disbursements would be tied to independently audited metrics, such as the number of flood incidents that did not occur and the amount of cubic meters that reached drought zones. Repayments would fluctuate in response to differential GDP performance compared to a counterfactual damage curve. Because adaptation capital typically yields internal rates of return in the mid-teens, the Fund would improve debt sustainability rather than weaken it. Satellite-verified runoff feeds could trigger algorithmic releases and cross-border compensation payments, stripping daily politics from operational hydrology. Such automation would make Brussels an umpire, not a water-lord.

Updating the Cost–Benefit Lens

Budget manuals still assume that a flood wall serves a single purpose: to hold back water. Under United Kingdom Treasury rules, that wall must show a five-to-one benefit ratio to obtain funding. The calculus changes once hydraulic assets are recognized as multi-use infrastructure. A diversion canal that traps winter surpluses recharges a coastal aquifer, depresses agriculture-price volatility, and raises reservoir head height for peak-hour hydropower suddenly earns benefits on four ledgers at once. Discounted at the sovereign rate, these hybrid projects repay their capital comfortably within a parliamentary term of five to seven years. They also generate revenue streams that can be securitized, opening the door to pension-fund participation in climate resilience rather than mere divestment rhetoric.

Choosing Hydro-Sovereignty

Europe is prosperous in sensors, civil engineers, and capital markets, but poor only in hydraulic imagination. Telemetry enables machine-learning flood nowcasts that add up to seventy-two hours of evacuation breathing space. Open-source evapotranspiration maps would allow farmers to reduce irrigation water usage by one-fifth without compromising yields. Progressive block tariffs can finance pipe replacements while reducing bills for households with the lowest water usage. This represents a crucial equity gain, as the poorest quintile already spends up to four percent of its disposable income on utility charges. All the building blocks are in place, yet public debate continues how best to distribute sandbags after the waters rise.

Two thousand years ago, China's rulers solidified their legitimacy by harnessing floods and droughts with a unified hydraulic vision. Twenty-first-century Europe faces the same civilizational test, but with far more powerful tools at its disposal. The choice is not between action and inaction; it is between engineered sovereignty and permanent vulnerability. If Europe seizes the moment to treat water as a shared, investible asset, it will no longer be trapped in cycles of televised catastrophe and reactive bailouts. Instead, it will transform climate risk into a continental dividend. When that future arrives, the headline after the next atmospheric river will not mourn record damages. It will announce record diversions — and with them, a Europe that chose ambition over drift.

The original article was authored by Matteo Ficarra and Rebecca Mari. The English version of the article, titled "Weathering the storm: The role of adaptation in mitigating the economic impact of floods,” was published by CEPR on VoxEU.