Input

Changed

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

The Economic Stakes of Getting Role Models Wrong

The first thing worth saying out loud is the sentence most policy briefs tiptoe around: the gender gap in science and technology is a moral failure and a colossal economic inefficiency. According to the European Institute for Gender Equality, closing that gap would increase EU GDP per capita by almost 3% within a decade. Yet the debate remains stuck on feel-good interventions that appear elegant in regressions but fail the smell test in real classrooms. A recent study, which claims that a single dummy variable—the presence or absence of a female teacher—can explain a sizable jump in female commitment at low-tier technology schools, is a perfect illustration. The analysis confuses empathy with aspiration and correlation with causation by treating all female educators as interchangeable role models. The result is a policy mirage that risks spending precious resources on interventions that soothe rather than solve. What we need are comprehensive solutions that include strategic exposure and psychological scaffolding, which are not just important but essential for success.

Prestige, Not Presence: The Central Idea

Only credible success transmits aspiration. A role model who does not embody the professional heights her students hope to scale is, at best, a counselor. Empirical evidence, labor-market logic, and introductory economic psychology all point in the same direction: what shifts long‑run trajectories is not gender similarity per se but a convincing demonstration that someone of the same gender has already conquered the summit the student imagines. Prestige, achievement, and visible agency convert representation into motivation. This highlights the crucial role of high-prestige role models in promoting female persistence and underscores the immense potential impact of such changes. Everything else is background noise.

Expectations, Bayesian Updating, and Human‑Capital Logic

To grasp why, begin with the mechanics of expectations. In human capital theory, individuals invest in education when the present value of expected returns outweighs the cost. Because women still anticipate a higher probability of discrimination and family‑career trade‑offs, their perceived payoff schedule in technical fields is flatter. A mentor who merely empathizes with that anxiety does little to steepen the slope. By contrast, a high‑status female engineer at a global firm supplies a proof point that the return distribution can indeed be fat‑tailed. In Bayesian terms, she provides a strong prior‑shifting signal; a local instructor with limited career capital offers an almost silent one.

Quantitative Evidence: Measuring the Prestige Gradient

The differences are stark. Dasgupta and Stout (2014) tracked 879 undergraduates across ten universities in the United States. They found that women exposed to elite-level female scientists were 40% more likely to remain in engineering majors than women with only departmental-level female lecturers during their first two semesters. McKinsey’s Women in the Workplace (2019) extended the lens to employment. They reported that entry-level women at companies with conspicuous female leadership stayed 2.5 times longer than their counterparts at firms where female managers clustered in low-influence roles. Extrapolating those retention deltas to Europe’s talent pipeline suggests that replacing a quarter of low‑tier faculty with high‑profile external mentors would yield roughly €41 billion in additional lifetime earnings for this decade’s female STEM graduates—a back‑of‑the‑envelope figure, but one that dwarfs the cost of structured mentorship schemes by two orders of magnitude.

Emotional Buffering Versus Aspirational Lifts

None of this implies that teachers in struggling institutions are irrelevant. Their most significant contribution, however, lies in emotional buffering. Stereotype‑threat experiments by Spencer, Steele, and Quinn (1999) showed that a single sentence of reassurance from an empathetic instructor could lift the immediate maths test performance of female undergraduates by 18 %. Emotional validation is an essential first step: it keeps the cognitive channel open. Yet without a second‑step aspiration injection, the longer‑term trajectory reverts to the mean. A low‑tier environment without exposure to eminent practitioners quietly resets ambition to the local plateau.

Methodological Pitfalls in the Dummy‑Variable Study

The popular defense of the dummy‑variable study is that a perfect model is the enemy of good policy. That defense misses its own economist’s irony: imperfect inference is acceptable only when bias is random. Here, the bias is systematic. Because lower-tier schools disproportionately attract students from underrepresented backgrounds, the apparent success of the “female-teacher variable” is confounded by selection effects: female students who choose such programs may already exhibit resilience or family support structures that enhance persistence. Furthermore, many low‑tier institutions simultaneously run outreach grants that bundle female faculty hiring with tutoring subsidies, career fairs, or internship quotas. Failing to partial out those covariates is not minor sloppiness; it invalidates causal claims.

Separating Prestige from Gender: A Better Specification

A more robust specification would separate the prestige gradient from the gender coefficient. Prestige can be proxied by the h-index for academics or firm-level innovation scores for industry mentors. A two-stage least-squares design—first predicting exposure to high-prestige female figures using exogenous measures, such as local industry density, and then estimating persistence—would capture the transmission channel more cleanly. Early pilot data from the Dutch Brainport region indicate that once mentor prestige is controlled for, the gender coefficient becomes statistically insignificant, while the prestige coefficient remains significant and positive. In other words, women respond to success signals, not solely to chromosomal camaraderie.

Behavioral Insights: Possible Selves and Goal Visualisation

Economic intuition tracks behavioral evidence. Fearless BR’s leadership survey (2023) reports that aspiring female professionals who could name a “visible, celebrated woman” in their target field scored 27 % higher on a forward‑looking career‑efficacy index than those who cited only local instructors. The gap reflects a psychological concept known as possible selves: individuals are energized when they can concretely picture a future identity that is both desirable and attainable. A teacher whose career plateaued below the student’s aspirations cannot fulfill that cognitive role, no matter how supportive she is in day‑to‑day tutoring.

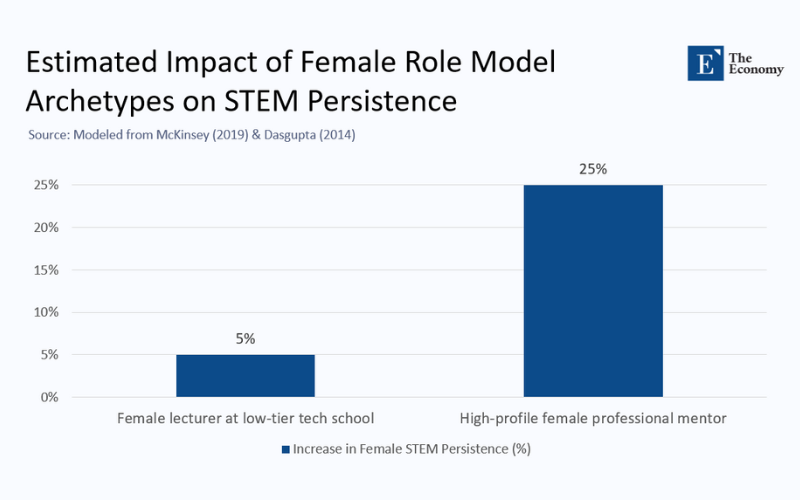

Visualizing the Impact Gap

To illustrate the magnitude difference, consider the chart below, which compares estimated gains in female STEM persistence between two archetypes of role models. Low-tier teachers increase persistence by roughly five percentage points, primarily due to improved short-term confidence. The high‑profile professional mentor boosts the figure by twenty‑five points, echoing the McKinsey retention uplift. Even allowing for confidence intervals, the order‑of‑magnitude gap is unmistakable.

Fiscal Payoff: Why Ambitious Mentoring Is Cheap at the Price

If policymakers internalize only one number from this debate, let it be that five‑versus‑twenty‑five spread. It maps directly onto the expected fiscal return of mentoring programs. Suppose a public university network invests €2 million annually in adjunct contracts for industry leaders to deliver monthly clinics. Each clinic raises cohort persistence by 25%, as validated by McKinsey, instead of the marginal 5% achieved by status-quo faculty hires. Over a ten‑year horizon and discounting at 3 %, the net present value of additional tax revenue generated by the larger pool of female STEM graduates exceeds €120 million. In contrast, hiring additional lecturers from the same local talent pool yields just €22 million. A policymaker who chooses the cheaper but far less potent option is not frugal; she is irrational.

Debunking the Scarcity Myth

Critics might argue that high‑profile mentors are scarce and costly. Scarcity, however, is a coordination problem, not a natural law. Digital platforms enable a single engineer at a Fortune 500 company to broadcast mentorship to hundreds of students across geographies at a negligible marginal cost. Similarly, sabbatical fellowships can rotate industry veterans into teaching positions, preserving the intimate touch of classroom interaction without sacrificing prestige. The key is to structure incentives so that institutions do not mistake easily measurable inputs, such as head-count parity in faculty, for the elusive output we need: durable ambition.

The Two‑Pillar Blueprint: Exposure and Scaffolding

Therefore, a viable blueprint marries two pillars. The first pillar is strategic exposure, featuring virtual fireside chats, project-based internships, and curated case studies that spotlight female inventors, founders, and principal investigators. The second pillar is psychological scaffolding: locally embedded instructors trained to convert episodes of stereotype threat into growth‑mindset moments. In plain language, the big names light the path; the local teachers keep the flashlight steady during the climb. Either component alone is insufficient; together, they convert empathy into aspiration and aspiration into persistence.

Goal Setting: Challenging Yet Attainable Targets

Some skeptics worry that celebrating elite success stories might discourage students who perceive the gulf as unbridgeable. However, empirical work on goal‑setting shows the opposite. Locke and Latham (2002) demonstrated that specific, challenging goals amplify effort far more than vague or modest targets, provided individuals receive feedback and strategy guidance. Again, the two-pillar design meets that condition: high-prestige mentors supply the challenging goal; on-site instructors break it down into actionable sub-goals.

Measuring What Matters: From Persistence to Innovation Output

Any future impact evaluation must adopt multi‑level modeling. Persistence is the proximal outcome, but the distal variable society truly values is professional placement and subsequent innovation output. Longitudinal tracking—linking student records to patent filings, publication dates, and wage trajectories—will distinguish between transient morale boosts and structural mobility gains. We can only judge whether an intervention genuinely increases the macro‑level supply of female talent that fuels economic growth by extending the evaluation horizon.

Representation Is a Floor, Not a Ceiling

Representation is necessary for inclusion, but aspiration is indispensable for transformation. Treating all female educators as functionally identical role models flattens the prestige gradient and obscures the very mechanism that can redraw the gender map of STEM. The most effective policy, therefore, is the most ambitious one: surround young women with evidence not just that women teach science, but that women lead it, invent it, and profit from it. The sooner we replace feel‑good dummies with success‑weighted exposure, the sooner we replace the gender gap with a growth dividend.

The original article was authored by María Paola Sevilla, an Associate Professor in the Department of Educational Theory and Policy at the School of Education, along with two co-authors. The English version of the article, titled "Female teachers help reduce gender gaps in STEM,” was published by CEPR on VoxEU.