Input

Changed

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

The policy levers that central banks and treasuries use are blunt because we continue to assume that every firm is the same size. Once you measure shocks through the lens of corporate scale, the macro story becomes a razor-sharp focus: large enterprises transmit and amplify disturbances, while small businesses mostly echo them.

A macro puzzle resolved by scale

For decades, standard models treated business heterogeneity as background noise. However, over the last two years, three independent datasets—European matched employer-employee records, customs files on exporters, and real-time energy-invoice panels—have all arrived at the same conclusion: the top tier of firms reacts more, earlier, and in distinct ways to every common shock that matters. This revelation significantly reshapes our understanding of macroeconomics and the role of firm size in it.

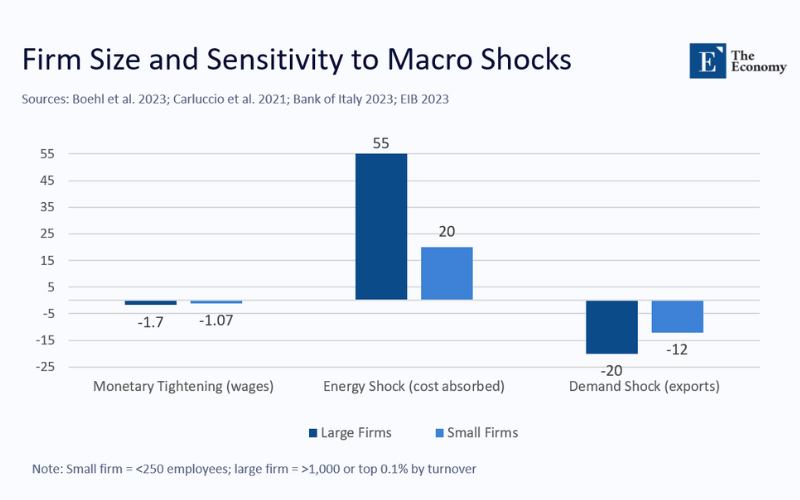

The implications of this study, released in March 2025 by ECB economists, are profound. It shows that after a routine 25-basis-point rate hike, wages at German companies with more than 5,000 employees fall about 1.7 percent within six quarters, compared with just over 1 percent at firms with fewer than 250 staff. This wage income from large employers represents roughly 40 percent of aggregate household purchasing power in the euro area. A policy shock that hits that slice harder reverberates through consumption, tax receipts, and GDP, underscoring the far-reaching impact of firm size on macroeconomic stability.

Large firms consistently show stronger or more buffered responses to major macroeconomic shocks. Whether the margin is wages, prices, or exports, firm size predicts not just the speed but the scale of adjustment.

The chart above visualizes how the pattern repeats under energy and demand shocks: in each case, the bar for large firms—dark blue in the figure—shows a steeper or flatter response than the bar for small firms, depending on the margin of adjustment. The direction changes, but the dominance does not.

From Covid demand collapse to export granularity

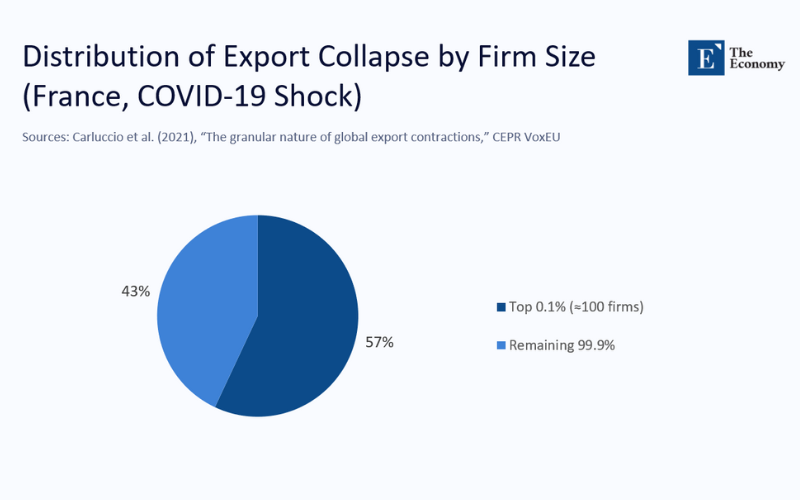

When COVID-19 froze world trade in the second quarter of 2020, French customs data tracked by Carluccio and co-authors reveal that the hundred largest exporters—barely a tenth of one percent of all exporters—were responsible for more than half of the nation’s 25 percent decline in overseas sales. A similar dominance had emerged during the 2008–09 financial crisis. Because these “granular” firms are embedded in global value chains, a modest shock in global demand becomes a wholesale contraction once mirrored across their worldwide subsidiaries. Their size, not their sector, turns a bump into a crater in the national accounts.

The mechanics matter. Giant exporters can pull three levers smaller rivals lack: they cancel just-in-time orders, reroute sales across regions, and delay capital expenditure—all within the same quarter. Each lever propagates the shock downstream: suppliers face inventory spikes, logistics providers lose volume, and local labor markets feel the chill. Macro volatility, in short, is no longer a mass phenomenon; it is a few heavy hitters moving first and fast.

The unequal burden of the energy crunch

Skip to the European energy crisis of 2021-22, and the same hierarchy emerges. Bank of Italy researchers exploited staggered expiry dates on fixed-price electricity contracts to show that small manufacturers passed roughly four-fifths of the extra cost straight to customers when wholesale prices trebled. In contrast, large corporations swallowed over half through cash buffers, financial hedges, or portfolio shifts to less-energy-intensive European Central Bank products. Survey data from the European Investment Bank put numbers on the stress: by late 2022, 87 percent of firms cited energy as a barrier to investment, up from 69 percent a year earlier, with the most significant burden falling on micro-enterprises in retail and hospitality.

Paradoxically, the giants’ capacity to absorb costs stabilized the consumer price index but squeezed their profit margins, triggering executive-level wage freezes that again hit mid-career professionals the most. Meanwhile, energy-exposed cafés and workshops had no choice but to raise final prices or close doors altogether. Scale dictates whether a shock is re-priced into inflation or channeled into labor income.

Monetary policy’s hidden distributional dial.

The European results mirror evidence from Japan. In December 2024, a Reuters investigation highlighted that small companies already spend nearly 70 percent of their profits on wages, versus about 40 percent for listed conglomerates, leaving little room for any booster shot to pay packets. When the Bank of Japan contemplates rate rises, it faces a trade-off: press too hard, and it will decelerate small-firm hiring before the aggregate wage gains needed to sustain inflation have time to materialize.

Across jurisdictions, the lesson repeats: interest-rate changes redistribute risk along the firm-size dimension before the first GDP release is printed. Ignoring that redistribution can make a central bank’s Phillips-curve estimates look wrong when, in fact, the curve is moving underneath a weighted average.

Why size drives sensitivity

Four structural forces give big companies their distinctive macro role.

First, they enjoy cheaper and more diversified funding, which lets them pivot across bond markets, bank credit, and internal cash when monetary or financial conditions tighten. Recent CEPR work shows that firms with heavy near-term debt rollover must react sharply to higher rates, even if they look solvent on book-value metrics. Those firms are disproportionately large.

Second, they operate with layered wage contracts—baseline pay, bonuses, equity grants—so management can cut variable elements without triggering the legal and reputational costs of layoffs. As the ECB study illustrates, that flexibility turns wages into the preferred adjustment margin under monetary shocks.

Third, global supply agreements provide multiple geographic escape hatches. If North American demand fades, an apparel behemoth can reroute output to Asia within weeks, while a small factory with a single customer set cannot.

Fourth, big companies live under a permanent spotlight from analysts and regulators. News about a policy change is immediately integrated into their decision frameworks, accelerating the first-mover effect documented in high-frequency financial conditions indices.

Inequality, volatility, and the two-track labor market

These structural channels create not just macro volatility but distributional churn. In a typical rate-hike cycle, white-collar staff at large companies accept bonus freezes, equity-option repricing, or capped overtime. Lower-income workers at smaller firms face shorter hours or dismissal. Both groups lose income, but through different mechanisms and on different timetables. Aggregated household surveys blur the contrast, masking deeper scarring in communities dominated by micro-enterprises. Therefore, policy debates on inequality that focus purely on education or the sector miss a crucial axis of divergence: employer scale.

The UK’s forthcoming employer national insurance contribution increase provides a live case. Think-tank analysis finds that many mid-sized retailers are cutting high-earner pay bands to offset the extra levy, while smaller hospitality venues speak openly of closing days or seasons to stay afloat. The same tax shock, two opposite responses, both tied to the size of the balance sheet.

Re-tooling stabilization policy for a granular economy

These findings force a rethink across the policy spectrum.

The monetary strategy needs to incorporate size-weighted Phillips curves. If large-firm wages are the shock-absorber, central banks cooling inflation risk overshooting on consumption because headline earnings appear resilient while household liquidity is silently deteriorating among professional cohorts.

Fiscal backstops should pivot from blanket employment subsidies to liquidity insurance lines that scale with turnover volatility. Instead of subsidizing every small-business wage, governments can guarantee working capital loans tied to local demand indices, letting viable firms bridge short but brutal revenue gaps.

Energy and climate instruments must avoid entrenching incumbent advantages. Auction-based efficiency grants, where award size reflects expected emissions cuts rather than historical energy bills, level the playing field without muting the carbon price.

Industrial diversification deserves equal billing. Export concentration multiplies global shocks. Tax credits for mid-tier exporters establishing first-time foreign affiliates, plus risk-sharing export-credit guarantees, can smooth the aggregate trade series by widening the set of shock carriers.

A new modeling frontier

The intellectual implications extend further. Dynamic stochastic models that still rely on representative producers systematically under-predict volatility and misallocate gains from stabilization. The remedy is straightforward: embed firm-size granularity into baseline frameworks. That means calibrating not just by sector but by the full distribution of sales, employment, and debt. Statistical agencies can accelerate progress by publishing national accounts split by a firm-size bracket on a quarterly, not annual, cadence.

Equally, stress-testing regimes pioneered for banks should be extended to the corporate sector. Suppose a handful of energy-intensive multinationals control a quarter of a country’s industrial output. In that case, regulators must know how a carbon price shock or swap rate spike affects their cash-flow projections. Capital-market disclosure rules already collect much of the data; the gap is in aggregating and publishing the results so that fiscal or monetary authorities can act preemptively.

The next shock will not be egalitarian

COVID-19, commodity spikes, and aggressive tightening cycles have destroyed any lingering case for the representative firm. When the next global disturbance erupts—geopolitical, epidemiological, or financial—it will again be channeled through companies' balance sheets big enough to move the needle. Policymakers who treat those firms as larger versions of the median enterprise will find their tools miscalibrated and their forecasts off by orders of magnitude.

A granular understanding of corporate scale transforms both diagnosis and cure. It reveals that macroeconomic management is no longer about shifting an amorphous supply or demand curve; it is about steering the behavior of a relatively small cohort of giants whose decisions ripple through thousands of suppliers and millions of paychecks. Therefore, stabilization in the twenty-first century is granular stabilization—targeted, size-sensitive, and data-rich. Anything less is a macro policy with the lights off.

The original article was authored by Alina Bobasu and Amalia Repele. The English version of the article, titled "Effects of monetary policy on labour income: The role of the employer,” was published by CEPR on VoxEU.