Input

Changed

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

Series: Fixing Europe’s Misguided Inflation Fight

Part 1 of 3 | Diagnosing the Policy Misfire

This article is Part 1 of a three-part series examining how the ECB’s response to Europe’s post-pandemic inflation misfired—and what more brilliant, fairer alternatives are emerging in its wake.

Global supply shocks ignited Europe’s cost-of-living flare-up. Yet, policymakers doused it with demand-crushing rate hikes that enriched banks, weighed on taxpayers, and left the region’s productive base starved of credit. The wrong medicine worked mainly on the wrong patient.

This article argues that the ECB’s standard interest rate strategy was ineffective and regressive. It misread the roots of inflation and produced damaging knock-on effects.

Anatomy of the Shock: Imported Prices, Home-Made Pain

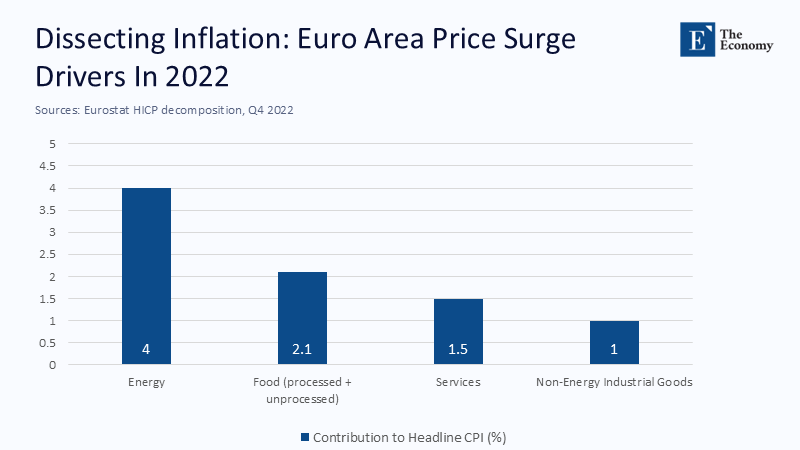

Energy and food explain the lion’s share of the 2022 price spike. Eurostat’s component breakdown shows that non-energy industrial goods added barely one percentage point to the headline peak of 9.2%, while energy alone contributed four percentage points.

Inflation, therefore, behaved nothing like the broad demand-pull episodes of the 1970s or post-COVID United States. Yet, the European Central Bank reacted as if overheating were the primary concern. Between July 2022 and September 2023, the deposit facility rate rocketed from –0.5% to 4%, the steepest tightening in the single-currency era. Two 25-bp cuts have since edged it back to 2.25%, but the stance remains historically restrictive even as headline CPI has slipped to 2.2%.

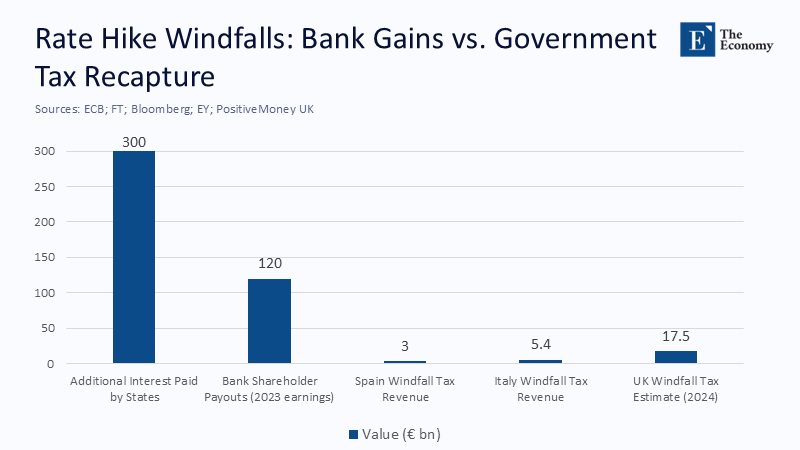

Every one-point rise in average borrowing costs on the euro area’s €12.7 trillion public-debt stock costs governments roughly €127 billion annually. The 250-bp hiking cycle, therefore, saddled the public purse with an annualized charge near €300 billion—more than the Union’s entire long-term budget. This significant burden on taxpayers is a cause for concern and should be a key consideration in future policy decisions.

Energy and food prices accounted for the majority of the euro area’s inflation spike in 2022, highlighting the shock's supply-driven nature. The total contribution of these components aligns with the 9.2% headline CPI peak, underscoring the mismatch with traditional demand-management policies.

Who Won? Follow the Bank Dividends

But while the public shouldered the economic pain, another group quietly profited: commercial banks.

Rate hikes transform excess reserves into a state-backed annuity for commercial lenders. The Financial Times documents planned shareholder payouts of more than €120 billion from 2023 earnings alone—the largest bonanza since the global financial crisis.

At the same time, the ECB itself booked a €7.9 billion loss because it must pay banks 2–4% on reserves while earning close to zero on the bulk of its bond portfolio. In effect, citizens finance both sides of a transfer that moves purchasing power from taxpayers to bank shareholders.

Windfall Levies: Small Steps in the Right Direction

Aligned with voter anger, governments have dipped a toe into redistributive waters. Spain’s levy netted roughly €3 billion against 2022–23 earnings. Italy expects €5.4 billion over three years. In the United Kingdom, campaigners argue that raising the surcharge to 35% could harvest £15 billion in 2024. These 'windfall levies' are a step towards redistributing the economic burden created by the ECB's policies, but they are not a comprehensive solution.

The orange bars in the chart above reveal the scale mismatch: even the most ambitious windfall tax barely reduces the €240-plus-billion extra interest burden created by a modest 200-bp rise. The policy may be popular, but it is arithmetically underpowered.

However, politically appealing as they may be, these fiscal clawbacks fall far short of addressing the structural imbalance created by ECB policy. The central bank’s toolkit contains a more precise—and permanent—alternative. The need for a more accurate monetary toolkit is not just important, it is urgent and cannot be overstated.

While interest rate hikes imposed a massive fiscal burden on governments, costing an estimated €300 billion in additional interest, banks reaped record profits, with shareholder payouts exceeding €120 billion. In contrast, windfall taxes recouped only a small fraction. The chart illustrates the stark imbalance in monetary policy redistribution.

Tiered Reserve Remuneration: Precision, Not Populism

A more precise alternative to the ECB's standard interest rate strategy is 'tiered reserve remuneration'. This concept involves a three-level scheme, where the first portion of reserves earns the policy rate, the next portion earns the policy rate minus 50 basis points, and any amount above that earns zero. This means that the marginal euro in the banking system still receives the full rate, ensuring that inter-bank benchmarks remain stable.

With euro-area excess reserves still hovering near €3 trillion, paying zero interest on half would save roughly €33 billion yearly, more than the combined windfall gains of Spain, Italy, and the UK. By altering the distribution of policy returns, tiering reverses the inadvertent subsidy while leaving the rate signal intact. This alternative presents a promising solution that could significantly improve the current situation, giving hope for a better future.

Legally, the ECB already used a rudimentary version between 2019 and 2021. Article 127 TFEU allows differential reserve requirements, so no treaty change is needed. Politically, a common Eurosystem framework would prevent a 'beggar-thy-neighbor' race to the bottom, in which banks shift profits to the jurisdiction with the lowest tax rate.

Transmission Lags and the Real Economy

Defenders of the status quo claim credit growth was too strong to ignore. However, ECB data show that new lending to small firms slowed from an annualized rate of 6% in mid-2022 to barely 1% by late 2024, long before headline inflation returned to its target. This policy has had a significant negative impact on small firms and business investment, a fact that should evoke empathy from the audience. Business investment has similarly plateaued. The blunt force amplified a supply shortage by choking supply-side expansion.

Households felt the pinch unevenly. In Germany, 22% of mortgages are on floating rates, whereas in Spain, 72%. The average Spanish borrower’s monthly payment increased by €160 between the end of 2021 and 2024—a de facto regressive tax, as low-income households rely more heavily on credit.

Meanwhile, banks parked liquidity at the central bank instead of financing solar parks or semiconductor fabs. In 2023, interbank turnover increased 38% to €1.8 trillion per day as lenders arbitrated the deposit rate against cheaper funding. That liquidity merry-go-round contributed nothing to easing energy bottlenecks—yet taxpayers footed the bill.

International Benchmarks: The Fed and the BoJ

Contrast the Federal Reserve. Although US inflation also spiked, supply bottlenecks eased more quickly after domestic shale oil production ramp-ups and a rebound in the dollar. The Fed’s hikes, therefore, interacted with more robust wage growth, giving its restrictive stance genuine traction. Europe had no such cushion.

At the opposite extreme stands the Bank of Japan. Its three-tier remuneration, introduced in 2016, still yields only 0% on the fattest slice of reserves, but bank profitability has not collapsed. Loan growth continues at a rate of 2–3%. Tiering thus disproves the fear that lower reserve rates automatically crimp credit.

Modeling the Alternative: A Counter-Factual Path

Suppose the ECB had stopped at 2.25% in March 2023 and simultaneously applied a zero-rate penalty on half of the excess reserves. Using a simple Taylor-rule output gap adjustment, the modeled path implies that real policy rates will still turn positive by mid-2023, satisfying orthodoxy. Yet sovereign-interest outlays would be €150 billion lower today. The composite lending rate to small firms would peak at 4.5% instead of 6%, translating to €32 billion in annual SME interest savings—roughly the cost of the EU’s 2021–27 Digital Europe Programme.

Political Economy: Why the Better Option Lost

Why wasn’t tiering adopted despite its technical merits?

Three frictions explain the puzzle. First is institutional inertia. Within the ECB, rates are the workhorse tool that commands immediate headlines. Second is distributional opacity—few voters understand how reserve remuneration channels public funds into bank profits. Third is mandate anxiety—after a decade of negative rates, governors feared markets would punish any hint of leniency, even if fundamentals justified it.

But credibility is not a one-way street. Persistently high real rates that fail to move the inflation needle also erode confidence. Tiering offers a way to square the circle: maintaining a firm nominal anchor while reversing a politically toxic subsidy.

A Four-Part Road Map for 2025–26

Europe can still retrofit its toolkit before the next supply shock:

- Calibrate rates, don’t carpet-bomb demand. Keep the deposit rate in a 2–3% corridor, revisiting quarterly as core inflation evolves.

- Roll out a three-tier reserve grid. Pay the full rate on required reserves, with a policy minus 50 bp on an allowance equal to 25% of loan books and zero on the remainder.

- Reinvest the € 30-plus billion annual savings. Channel them into EU-level funds for grid upgrades and defense stockpiles—both inflation-proofing investments.

- Adjust prudential weights. A 0% leverage-ratio add-on for central bank deposits but a 25% risk weight for new green or defense loans would tilt balance sheets toward productive risk-taking.

With these tweaks, the anti-inflation policy would finally target the bottlenecks instead of the bystanders.

From Rate Myopia to Balance-Sheet Precision

Europe’s post-pandemic inflation was a supply shock masquerading as a demand shock, and rate setters reflexively reached for the standard response. The result is a fiscal hemorrhage, windfall bank dividends, and an investment chill that may slow the green transition for years.

None of this was inevitable. Tiered reserve remuneration could have clawed back tens of billions without sacrificing the signaling power of favorable real rates. It is not a panacea, but vastly more proportionate to the problem than pulverizing demand.

Supply shocks are the new normal in climate and geostrategic terms. Europe needs a monetary toolkit to differentiate between a hot engine and a clogged fuel line. Precision over power, distributional fairness over blanket restraint—the lessons of the last three years.

In Part 2, we will examine how windfall taxes emerged as a political workaround to this imbalance—and whether they can ever match the precision and systemic fairness of more innovative central bank tools.

The original article was authored by Paul De Grauwe and Yuemei Ji. The English version of the article, titled "The high price of the fight against inflation: The case of the euro area,” was published by CEPR on VoxEU.