Input

Changed

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

Part 2 of 3 | Searching for Better Tools

This article is Part 2 of a three-part series analyzing the ECB’s flawed response to post-pandemic inflation. In Part 1, we explored how aggressive rate hikes misfired against a supply-driven shock, enriching banks and burdening public budgets. Here, we examine two policy reactions to this imbalance—windfall taxes and tiered reserve remuneration—and argue that only the latter offers a systemic, scalable solution.

The Costly Aftermath of a Misread Shock

Part 1 showed how the ECB treated a supply-driven surge in energy and food prices as if it were classic demand overheating, lifting the deposit facility rate from –0.5 % to 4 % between July 2022 and September 2023. Because banks still hold roughly €2.8 trillion in excess reserves, every percentage-point increase in the policy rate now diverts about €28 billion a year from taxpayers to bank treasuries. Over 2022-24, the cumulative transfer reached an estimated €270 billion—more than triple the EU’s entire Horizon Europe research program.

Commercial lenders did not sit idly on the windfall. According to analysts cited by Reuters, they plan to return a record €120 billion to shareholders from their 2023 profits—the richest distribution since the global financial crisis. At the same time, the ECB itself incurred a €7.9 billion loss because it must pay 2–4% on its reserves, while earning close to zero on its bond portfolio, and suspended the dividends typically paid to national treasuries. The fiscal asymmetry is stark: citizens finance higher sovereign-interest costs and a deluge of banking dividends.

Windfall Taxes: Small Revenue, Big Illusion

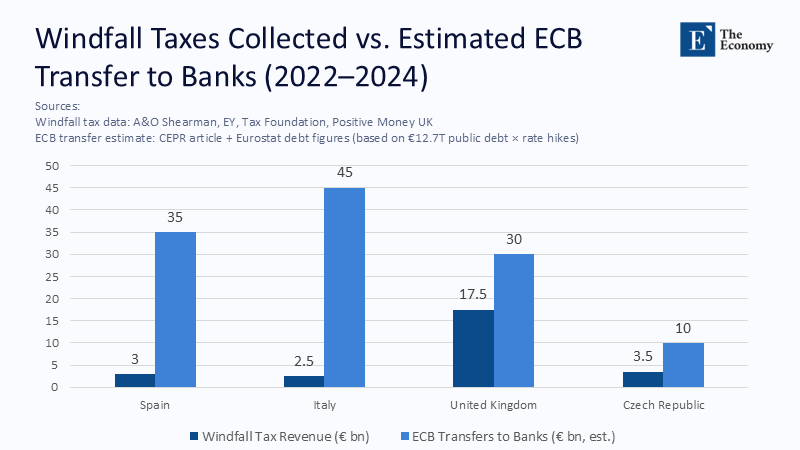

Enter politics. Spain slapped a 4.8 % net interest and fee income levy, raising about €3 billion against 2022-23 earnings. Italy announced a 40 % charge on the net-interest income gap between 2021 and 2023, only to neuter it after market turmoil; the revised cap has yielded effectively zero. In the United Kingdom, campaigners argue that reviving the bank surcharge at 35 % could fetch £15 billion (€17.5 billion) in 2024—roughly six percent of the euro-area transfer.

A&O Shearman’s survey of European measures finds similar efforts in the Czech Republic, Hungary, and Lithuania but warns that narrow tax bases, complex exemptions, and constitutional challenges will keep yields modest. Even if every euro-zone government cloned Spain’s design, gross revenue would struggle to exceed €40 billion, scarcely one-eighth of the rate-hike subsidy.

Numbers aside, windfall taxes share three structural flaws. First, they are reactive: policy-created profits materialize before the tax is due, so the state must chase revenue rather than prevent leakage. Second, the “excess” profit base is fiendishly hard to pin down once margins and balance-sheet mix evolve. Third, profits (and tax receipts) fall when credit slows, precisely when public finances need support.

A Leaky Framework: How Banks Evade Windfall Taxes

Design headaches multiply in a single-market currency union. Large banks can transfer treasury operations from a high-tax jurisdiction to a low-tax one with little more than an intra-group booking adjustment. Italy’s experience is instructive: within a week of the August 2023 decree, analysts tallied more than €10 billion in lost market capitalization as investors factored in relocation risks. The government quickly revised the law, capping liability at 0.1% of assets and allowing a capital-buffer option instead of a cash payment. Revenue estimates collapsed from €4.9 billion to about €2.5 billion.

Corporate tax specialists predict a similar dynamic if windfall levies become permanent. Banks can slide liquidity books into subsidiaries outside the levy’s perimeter or funnel profits through higher-fee intragroup trades. Each complexity tier widens the gap between headline rates and cash collected while lawyers and accountants thrive.

Tiering: Plugging the Leak Before It Starts

A tiered reserve-remuneration grid is a system in which banks are paid different rates on their reserves based on the amount they hold. This system reverses the logic of windfall taxes. Instead of taxing windfalls after they appear, the Eurosystem would pay a lower rate on excess reserves that exceed a generous allowance. The Bank of Japan has employed a three-tier scheme since 2016: required reserves earn 0.1%, a buffer slice earns zero, and any balance above is charged– 0.1%. This system ensures that banks are not penalized for holding excess reserves, and it has been successful in Japan, where loan growth remains at 2–3%. Bank return-on-equity has risen, evidence that reserve pricing need not cripple credit.

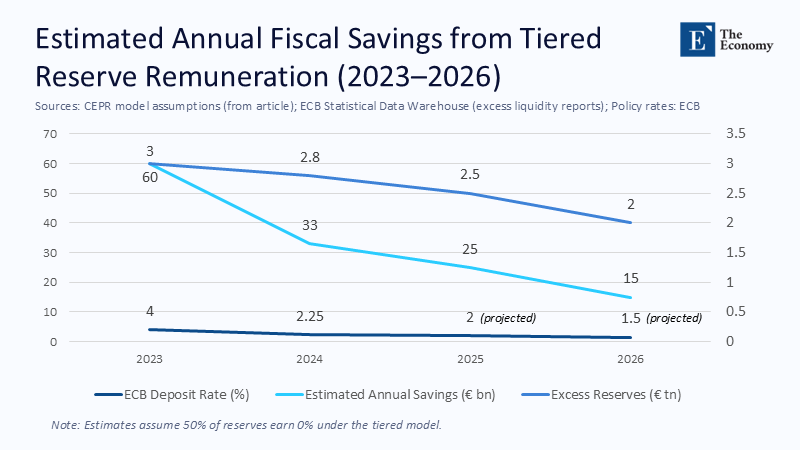

Applied to the euro area, the math is compelling. With today’s €2.8 trillion excess-liquidity stock, paying zero on half would save €33 billion annually at the current 2.25 % deposit rate. Had the grid been in place during the 2023 peak, annual savings would have topped €60 billion—more than every announced national windfall tax combined.

Critically, the legal framework already exists. From 2019 to 2021, the ECB exempted reserves six times the required amount from negative interest rates. Article 127 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the EU empowers the Eurosystem to set differential reserve requirements, so no treaty change is needed—merely a Governing Council vote.

Stress-Testing the Grid

Applying a zero rate to the top reserve slice trims the aggregate net interest margin of the euro area’s 30 largest banks by roughly six basis points—small next to the 140-bp windfall they booked between 2021 and 2024. Despite tiering, analysts project return-on-equity comfortably above the pre-pandemic norm of 7–8 %. A stylized balance-sheet model shows that if the deposit rate fell to 1.5 % in 2026, tiering would still yield €15 billion a year—permanent fiscal room to fund, for example, half the EU’s annual defense investment shortfall.

Because reserve balances are concentrated in France, Germany, and the Netherlands, tiered pricing would help temper intra-euro zone imbalances. Banks in surplus countries would relinquish the bulk of today’s subsidy. At the same time, lenders in capital-scarce periphery states—where reserves are thin—would lose little income but gain a level of competitiveness.

Redirecting Savings to Real Economy Investments

Redirecting even half of the recurring €33 billion saving could finance a European Energy Infrastructure Fund capable of doubling annual investment in cross-border grid connections. According to Commission modeling, that alone would shave an estimated 0.4 percentage points off wholesale power-price volatility—an inflation dampener far more potent than another rate rise. Alternatively, a Defence Procurement Facility of the same size could plug the ammunition gap revealed by the war in Ukraine within three years. Either route reinforces supply capacity, addressing the bottlenecks that sparked the 2022 price shock.

Credibility, Fairness, and the Politics of Reform

Sceptics worry that tweaking reserve pay-outs signals a softer stance. Yet credibility is not a one-way street. Enduringly high real rates that do not reduce supply-side inflation while directing public funds to bankers erode trust just as certainly as premature loosening. Tiering maintains the headline rate—markets’ primary signal—while neutralizing an inequitable side effect. Surveys for the European Parliament show that 71 % of voters support “fair share” contributions from banks; a rules-based grid achieves that with less legal fragility than ad-hoc taxes.

The alternative—rolling annual profit levies—locks policymakers into a permanent state of trench warfare with well-funded lobbyists. Each budget cycle re-litigates last year’s rate choices, distracting from a forward-looking monetary strategy. Embedding tiering in the operational framework quarantines the distributional issue, freeing the Governing Council to focus on its price-stability mandate.

A Twelve-Month Implementation Roadmap

April 2025: The ECB announces that starting with the September reserve-maintenance period, required reserves plus an allowance equal to 25 % of each bank’s loan book will earn the policy rate; the next 25 % band earns policy minus 50 bp; balances above that earn zero.

June–August 2025: The Single Supervisory Mechanism amends the leverage-ratio add-on, reducing the weight on central bank deposits to zero so that funding incentives remain neutral. National treasuries prepare to phase out existing windfall-profit taxes.

September 2025: The grid goes live. Six weeks later, money-market benchmarks show a negligible change in EONIA/€STR spreads, confirming intact pass-through. Fiscal agency projections record a net interest saving of €2.8 billion for the fourth quarter alone.

January 2026: Eurogroup finance ministers formally redirect half of the prior-year savings into the Energy Infrastructure Fund and the other half into a standard Defence Procurement window, converting monetary policy housekeeping into visible public goods.

Build the Valve, Not the Bucket

Windfall taxes are politically cathartic but fiscally anemic. They chase profits after the horse has bolted, encourage arbitrage, and must be rewritten yearly. Tiered reserve remuneration shuts the stable door first. It preserves the ECB’s rate signal, restores distributional neutrality, and recycles tens of billions into Europe’s strategic priorities without raising headline tax rates or public debt stocks.

As supply shocks linked to climate, geopolitics, and demographics become the economic norm, Europe needs monetary plumbing to distinguish between an engine running hot and a clogged fuel line. Precision beats power; structure outperforms spectacle. Having misdiagnosed the 2022 inflation surge, policymakers now have an opportunity to update their toolkit before the next shock occurs. They should seize it—because the cheapest windfall is the one that never leaves the public purse.

The original article was authored by Paul De Grauwe and Yuemei Ji. The English version of the article, titled "The high price of the fight against inflation: The case of the euro area,” was published by CEPR on VoxEU.