Input

Changed

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

Part 3 of 3 | Designing an Inflation Firewall

This article is Part 3 of a three-part series examining Europe’s flawed monetary response to supply shocks. Part 1 diagnosed the ECB’s interest-rate misfire and its regressive fiscal fallout. Part 2 contrasted reactive windfall taxes with proactive tiered reserve remuneration. In this final installment, we explore how to embed those insights into a structural, forward-looking facility that restores fiscal resilience and supports strategic investment across the euro area.

The Loop Europe Can’t Afford to Repeat

Europe has now endured three iterations of the same policy loop, each time facing a global shock that pushes prices higher. The European Central Bank, faithful to a demand‑management tradition forged in a different era, responds with brisk rate increases. This pattern, if left unchecked, could lead to a significant loss of fiscal space just as governments are asked to shield households and firms from the shock. In the following scramble, finance ministries reach for temporary taxes or subsidies that satisfy voters in the short run while barely denting the underlying imbalance. Parts 1 and 2 of this series dissected that cycle in detail. The first essay demonstrated how the ECB’s 2022–23 hiking campaign, aimed at a supply‑side surge in energy and food prices, transferred roughly €270 billion from taxpayers to bank treasuries and still left core inflation stubbornly above target. The second essay compared two answers to that distributional mistake—windfall levies and tiered reserve remuneration—and showed why only the latter offers a scalable, durable antidote to future miscalibration.

Beyond the Fix: Addressing Structural Gaps

Yet even a perfected tiered grid remains a partial remedy. It stops the subsidy to banks and recoups tens of billions for treasuries, but it does not, on its own, convert a blunt‑force monetary system into a forward‑looking shield against supply shocks. Nor does it tackle the deeper incentive problem that drives liquidity toward safe central bank deposits instead of the risky, productive investment Europe needs to decarbonize its grids, restore critical industry, and rebuild defense capacity. That is the gap this final article addresses. If Parts 1 and 2 diagnose the ailment and isolate a promising medicine, Part 3 asks how to embed that medicine in the patient’s daily diet so the disease never gains a foothold again.

The Arithmetic of the Next Shock

The macro arithmetic underlying the challenge is straightforward and sobering. ECB simulations suggest that another energy squeeze on the scale of 2022—an International Energy Agency scenario in which oil tops 135 dollars a barrel by 2027 and gas supply from Russia flat‑lines—would push headline HICP back above six percent for at least half a year. Replaying the 450‑basis‑point tightening of the last cycle under such conditions would add around €180 billion a year to sovereign interest bills while shaving barely four‑tenths of a percentage point from core prices after twelve months. On present debt stocks, every percentage‑point rise in the deposit rate shifts about €28 billion from public budgets to commercial banks. As the 2023 dividend season reminded everyone, those banks funnel the windfall to shareholders. Windfall taxes, however aggressive, recoup at best one euro in eight and often far less because the narrow tax bases that can survive constitutional scrutiny are easily arbitraged in a borderless banking market.

The Proposal: An Inflation Firewall Facility

If repeating that loop is intolerable, the natural conclusion is that the euro area must install a standing mechanism able to drain surplus liquidity without bleeding the fiscal accounts and reroute the savings into investments that blunt future supply shocks. It must work automatically, free of annual trench warfare in Ecofin councils or Governing‑Council press conferences, yet remain entirely consistent with the ECB’s mandate and the treaties. Call the solution an Inflation Firewall Facility. The label is less important than its architecture, which rests on three mutually reinforcing planks.

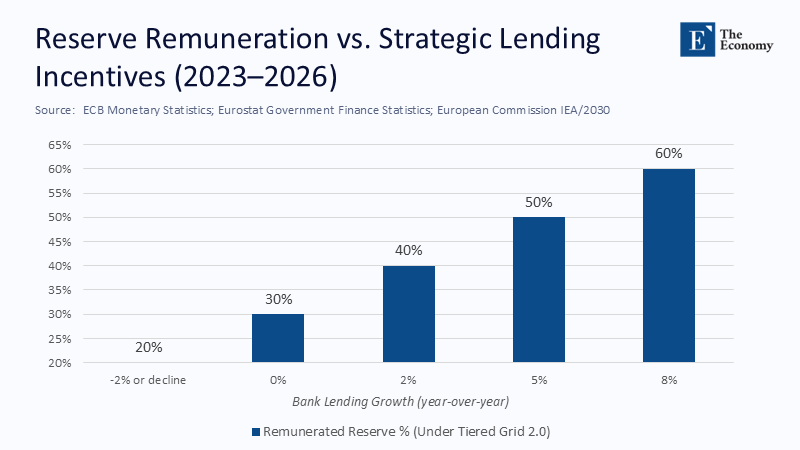

Tiered Grid 2.0: Linking Incentives to Lending

First comes a Tiered Reserve Grid 2.0. The grid examined in Part 2 would pay zero on about half the €2.8 trillion stock of excess reserves, saving thirty‑plus billion euros a year at current rates. The upgraded version would make a bank’s zero‑rate allowance conditional on how it expands targeted credit—for example, loans to small firms, renewable‑energy infrastructure, or dual‑use defense suppliers. A lender that grows such assets by five percent annually would keep the full allowance. One that lets its loan book stagnate would forfeit a larger share to the zero‑rate tier. The beauty of that rule is its symmetry: it does not punish liquidity but ends the practice of rewarding inactivity with a public annuity.

Recycling Reserves into Real Investment

The second plank is an ECB‑EIB swap line. Instead of allowing the fiscal savings to vanish inside national budgets, the ECB would reinvest them in five‑year floating‑rate notes issued by the European Investment Bank. The EIB would deploy the funds exclusively on cross‑border electricity interconnectors, green‑hydrogen corridors, or joint procurement of critical defense components—projects whose inflation‑mitigation value is direct and measurable. The ECB's balance-sheet risk is unchanged because the swap trades one high‑quality euro‑denominated asset (bank reserves) for another (EIB floaters). The EIB already carries a triple‑A rating; several core sovereigns do not.

Automatic Response to External Price Surges

A third plank provides an automatic counter‑shock buffer. Suppose imported energy prices rise more than thirty percent year‑on‑year in euro terms. In that case, the zero‑rate band will widen from fifty to seventy percent of excess reserves for twelve months, swallowing the extra bank margin before it can morph into dividend announcements. When energy prices normalize, the band shrinks, removing stimulus just as quickly. In other words, the system breathes with the shock, absorbing fiscal strain in real-time rather than forcing governments to legislate after the damage is done.

Fiscal and Growth Impact Over Time

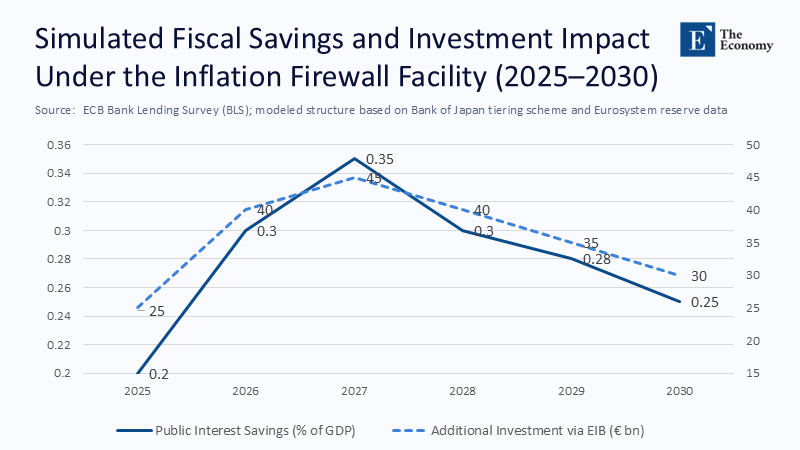

Quantitatively, this trinity is powerful. Even at the present 2.25 percent deposit rate, it would sterilize about €1.4 trillion of liquidity, trim aggregate bank net‑interest margins by eight basis points—still leaving them far above pre‑pandemic levels—and redirect roughly a quarter‑per‑cent of euro‑area GDP each year into infrastructure that lowers future price volatility. Over a five‑year horizon, the public interest savings exceed €150 billion, while the cumulative additional investment is approaching €180 billion. The Commission’s macro model indicates that such a profile raises potential output by over half a percentage point by 2030, enough to offset two‑thirds of the negative supply impact from the IEA’s high‑oil scenario. This potential for significant positive effects should inspire confidence in the proposed solution.

No Treaty Change Required

None of this requires a treaty change. Article 127(2) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the EU already authorizes the Eurosystem to conduct credit operations with credit institutions. The ECB’s 2011 Securities Markets Programme set an institutional precedent for swapping reserves for supranational assets, and from 2019 to 2021, the Bank used a rudimentary two‑tier system to cushion negative‑rate side effects. Linking the size of a remunerated allowance to credit‑growth metrics does not violate the equal‑treatment clause because the criteria are transparent, rule‑based, and identical for all. Operationally, the ECB and national supervisors already collect granular data on SME and green‑loan flows to administer TLTRO discounts; extending the feed to reserve remuneration is an IT project, not a legal revolution.

Anticipating and Addressing the Objections

Predictable objections will surface, yet none will withstand scrutiny. Some will claim the arrangement blurs monetary and fiscal spheres. It delineates them more cleanly: the central bank alters a parameter inside its toolbox, while elected finance ministers, acting through the EIB, decide how to deploy the savings in line with EU‑level mandates. Others will worry that markets will fear ECB balance‑sheet risk. However, reserves are not default‑free; they are simply ECB liabilities. Swapping one liability for a matched, high‑grade asset improves, not weakens, balance‑sheet robustness. A third concern is competitive neutrality. Tying remuneration to productive credit does tilt the playing field—but in the direction European industrial policy now demands—banks that expand real‑economy lending benefit; those that live off risk‑free carry trades do not.

Fast but Sustainable Rollout

Implementation could proceed quickly. A memorandum of understanding between the ECB and the EIB by late 2024, a one‑month consultation on the technical framework, grid activation in July 2025, and the first swap tranche before year‑end. Money-market spreads should confirm that the core policy signal remains intact six weeks after launch. By the first quarter of 2026, fiscal agencies would already record multi‑billion‑euro interest savings, while the EIB’s project pipeline would show concrete transmission to energy and defense investment. Success would not be measured in headlines but in what fails to happen: no emergency Ecofin meetings, no populist clamor for bank‑profit raids, and no widening of sovereign‑bond spreads as fiscal space erodes.

From Plumbing to Purpose

The broader macro‑political dividend is credibility. When a central bank demonstrates it can maintain a positive real policy rate without imposing a regressive tax on the public purse, skepticism about its independence fades, not grows. When voters see excess‑reserve cash re‑directed to tangible public goods—grid connectors that lower their electricity bills or an ammunition plant that shores up European security—they are less likely to dismiss price stability as an elitist abstraction.

Europe cannot rely on luck to avoid the next supply shock, nor can it afford another cycle of blunt hikes and patchwork fixes. Having miscalibrated its response once and debated fiscal claw‑backs to little effect, the euro area can now transform monetary plumbing from a liability into a strategic asset. A tiered grid cleans the pipes; an Inflation Firewall Facility installs the valve that channels flow where it strengthens resilience. Build the valve before the next flood, and the continent may finally escape the loop that has hobbled its policy every time the global tide turns.

The original article was authored by Maximilian Konradt and Giacomo Mangiante. The English version of the article, titled "The unequal costs of carbon pricing in European regions,” was published by CEPR on VoxEU.