Input

Changed

This article was independently developed by The Economy editorial team and draws on original analysis published by East Asia Forum. The content has been substantially rewritten, expanded, and reframed for broader context and relevance. All views expressed are solely those of the author and do not represent the official position of East Asia Forum or its contributors.

“Great powers are remembered less for the wars they win than the futures they finance.” That maxim captures the magnitude of the strategic misstep now unfolding in Washington. In just three months, President Donald Trump’s administration has proposed slashing the international-programs budget by 47 %, including an 83 % reduction in USAID’s global workforce and shrinking new foreign-affairs budget authority to a mere US$ $9.6 billion—an 84 % decline from 2025 levels. This is not mere fiscal restraint but a deliberate abandonment of the single most potent instrument through which the United States converts its values into durable influence. By engineering an aid shock unmatched since USAID’s creation amid the geopolitical urgencies of the late 1940s, Washington signals that it will cede the development arena just as global competition reaches its apex.

Miserliness as grand strategy: lessons from the Middle Kingdom

Scholars at East Asia Forum draw a compelling parallel between Trump’s austerity-driven approach and the “miserly convergence” long associated with China’s imperial and modern statecraft. Over centuries, successive Beijing regimes sustained a tributary order on the cheap, disbursing token gifts insufficient to forge genuine loyalty while relying instead on coercion or commercial leverage. In the twenty-first century, China’s “aid” spends little on grants or capacity-building; it favors policy-bank loans and infrastructure contracts that serve Chinese state-owned enterprises. That pattern reflects a core tenet: power derives from controlling strategic knots rather than underwriting public goods. By emulating that logic, the United States risks forfeiting its most significant competitive advantage—its reputation for open-handed support of health, education, and democratic governance, just as Beijing’s model proves transactional and narrow.

Quantifying the retreat: the data speak for themselves.

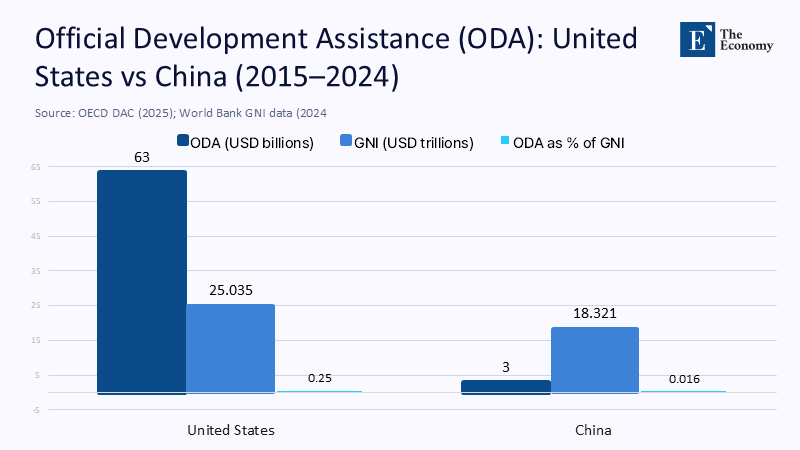

The scale of this reversal crystallizes when plotted against the last decade’s trends. Even amid the global aid contraction prompted by COVID-19, the United States led all DAC members in 2024 with US$ $63.3 billion in official development assistance (ODA), accounting for nearly one-third of the collective total. By contrast, China’s comparable outlays peaked near US$ $7 billion between 2015 and 2018, then plunged to US$ $2.85 billion by 2024, according to Brookings’ analysis of MOFCOM and CIDCA budgets. Under the administration’s proposal, America’s ODA would slip below levels China maintained through its austerity, effectively erasing the gap illustrated in Figure 1.

Yet absolute spending tells only part of the story. As Figure 2 demonstrates, America’s generosity translates into a far higher sacrifice of national income: US ODA equaled 0.25 % of Gross National Income in 2024, compared with China’s meager 0.016%. That tenfold multiple underscores that US aid is not merely larger in the aggregate but reflects a domestic willingness to budget real sacrifices for global public goods. Trump’s cuts would collapse that ratio toward Chinese levels, signaling a retreat in both leadership and commitment.

Hidden costs: security externalities and geopolitical gaps

Foreign aid is political technology, not philanthropy. USAID’s network of approximately 10,000 experts has served as the nerve center, enabling US embassies to translate humanitarian objectives into strategic alliances, market access, and intelligence partnerships. In the Pacific, where Australia’s Lowy Institute warns of a “soft power surrender,” countries from Vanuatu to Samoa now eye Beijing’s overtures with fewer viable alternatives. As US assistance retreats, allied nations must redirect precious defence and diplomatic budgets toward humanitarian gaps, undermining collective security frameworks. The opportunity cost thus compounds: initial savings on aid budgets sow strategic indebtedness in regions critical to Indo-Pacific balance.

In sub-Saharan Africa, the same calculus holds. US-funded HIV programs under PEPFAR have driven infection rates down by 60 % in high-burden countries since 2004. A sudden contraction of even a third could reverse decades of progress, worsen public health, and reignite governance fragility. Simultaneously, China’s tied loans for roads and ports—often opaque and laden with debt clauses—gain traction as Washington’s developmental presence thins. Governments confronting the choice between near-term infrastructure and long-term capacity-building are likelier to embrace the former when the latter vanishes.

Why Beijing wins even without spending more

Paradoxically, China does not need to increase its ODA to profit from America’s retrenchment. Beijing’s fiscal constraints—economic rebalancing, demographic headwinds, rising social spending—make a dramatic aid surge improbable. Yet influence is a relative metric. If Washington withdraws, static Chinese flows fill the void and gain outsized returns. Furthermore, Chinese concessional loans often secure physical collateral—mineral rights, port leases, telecom spectrum—ensuring direct returns to Beijing. In such a landscape, Chinese soft power leverages state-led commercial instruments as an indirect yet effective force multiplier. Without USAID’s governance-focused grants to counterbalance, recipient nations face diminished negotiating leverage, drifting deeper into Chinese orbit.

The UK’s Foreign Secretary, David Lammy, recently warned that merging aid and diplomacy at home—his reference to the UK’s DFID-FCO merger—has diminished British soft power and could foreshadow America’s fate. Even if China’s aid budget remains static, it reaps the benefits of a vacated stage, reinforcing its portrait as a reliable partner, even if that reliability comes with strings.

Toward a reimagined aid architecture

A slash-and-burn is not fiscal prudence but strategic self-harm. Genuine efficiencies do not require abandonment but redesign. First, the United States should pivot USAID’s portfolio toward catalytic finance: blending federal grants with multilateral guarantees and local-currency facilities that draw in private capital. Historical evaluations indicate that each US$ $1 billion in guarantees can mobilize up to US$ $10 billion in private-sector investment, preserving developmental impact even amid constrained budgets. Second, aid flows must be embedded in a wedge-strategy that rewards governance reforms: linking disbursements to transparent benchmarks in rule-of-law, civil society freedoms, and environmental stewardship. By consolidating at least 0.35 % of GNI for ODA—a compromise between current US targets and the UN’s 0.7 % aspirational goal—Washington can reaffirm its moral differentiation without igniting domestic political backlash. A G7 “Generosity Compact,” coupled with co-financing statutes, would amplify allied coherence, ensuring that no single administration can single-handedly hollow out the architecture.

An educational imperative for future policymakers

For an online education journal, this episode is a premier case study in the political economy of international relations. It illustrates how domestic budget debates ripple through global governance structures; how historical analogies—imperial China’s thrift—illuminate modern grand strategy; and why quantitative literacy (graphing aid flows, discounting concessional loans, modeling health and credit impacts) is indispensable for sound policy analysis. Students might engage in scenario modeling: projecting how a 30 % cut to PEPFAR funding affects HIV incidence curves, or simulating sovereign-bond yield movements under alternative Chinese debt-for-equity risks. These exercises, grounded in empirical metrics, train analysts to marry data with geopolitics, preparing the next generation for stewardship of soft power.

Generosity as geopolitical grammar

Power is “the art of securing tomorrow’s obedience with today’s gifts,” as historian John Strayer observed. The United States once mastered that art, underwriting post-war institutions and alliances that transcended political cycles. Trump’s proposed USAID cuts invert that logic, substituting calculated scarcity for confident largesse. History’s verdict on China’s frugality is clear: tribute was accepted, but rarely forged genuine integration under the imperial order. By chasing that same miserly posture, Washington risks learning the hard lesson from the wrong side of history. In the grammar of geopolitics, generosity is not charity; it is syntax. Remove it, and the sentence conveying American leadership no longer parses.

The original article was authored by Shahar Hameiri and Lee Jones. The English version, titled "Trump’s USAID cuts only accelerate the West’s miserly convergence with China," was published by East Asia Forum.