Input

Changed

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

Europe’s security debate still revolves around procurement tallies—how many tanks, fighter jets, and missiles each nation can field. Yet Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine laid bare a crucial truth: victory demands more than machines. A €10 million Leopard 2 tank immobilized because its crew cannot reset a software fault is not a symbol of strength but strategic self-deception. Absent well-trained, adaptable soldiers and non-commissioned officers, even the most advanced hardware becomes a liability, not an asset. If Europe hopes to deter aggression or prevail in conflict, it must elevate human capital—education, training, leadership development—above mere matériel.

Rethinking the Russo-Ukraine War: People First, Weapons Second

When Russia rolled its formidable columns into Ukraine in February 2022, it boasted numerical and technological advantages: modern T-90 and T-72 tanks, Sukhoi fighter-bombers, S-400 air defenses, and vast artillery stocks. Yet within weeks, those strengths frayed under Ukrainian tactics and training scrutiny. Russian units repeatedly blundered into minefields, lost logistical support, and abandoned high-value platforms for lack of basic maintenance and battlefield decision-making. A top U.S. intelligence report bluntly cited “poor planning, lack of movement, weak command, insufficient training” as the drivers of Russia’s early failures.

By contrast, Ukraine’s forces, though initially outgunned, leveraged nearly a decade of NATO-led training reforms (following the 2014 annexation of Crimea) to develop a cadre of junior leaders adept at decentralized warfare. Ukrainian anti-tank teams, drilled on Javelin and NLAW missiles, ambushed Russian armor with precision. Once the purview of special forces, small drones became ubiquitous reconnaissance tools in infantry hands. Creative tactics, such as rapidly relocating artillery after each salvo, frustrated Russian counter-battery efforts. The outcome was stark: well-trained Ukrainian brigades inflicted disproportionate losses on a numerically superior foe, capturing or destroying hundreds of Russian tanks and armored vehicles. Their success lay not merely in possessing advanced weapons, but in their ability to operate, maintain, and innovate with them under fire.

The Illusion of Hardware Dominance

Public discourse often treats sophisticated armaments as talismans of security: more jets equal air superiority; more tanks equal ground dominance; more drones equal battlefield awareness. Yet the empirical record tells a different story. In Ukraine’s summer 2023 counteroffensive, Western-supplied Leopard 2 tanks and Bradley Fighting Vehicles spearheaded assaults into well-defended positions. Early press coverage emphasized kit failure—broken drives, jammed turrets, burnt-out engines—leading some commentators to question the value of Western gifts. Ukrainian officers, however, pointed to “two months of training to understand how to operate the equipment—a very short period” as the true culprit. Units lacking robust gunnery practice, mine-breach experience, and logistics coordination found their new vehicles more vulnerable, not because the hardware was flawed, but because crews had not internalized their capabilities and maintenance routines.

Maintenance woes underscore this point. Sophisticated howitzers like the U.S. M777 require detailed upkeep unfamiliar to soldiers accustomed to simpler Soviet-legacy guns. In late 2022, Western artillery units in Ukraine reported barrel failures and hydraulic leaks at unprecedented rates after firing at near-maximum sustained rates. The U.S. responded by establishing repair depots in Poland; American maintenance teams toiled around the clock to refurbish incoming guns. The logistical scramble revealed a harsh truth: “Poor maintenance can be attributed to the lack of crew training,” especially when wartime exigencies forced crews into action before they were fully prepared. Russia, too, suffered maintenance breakdowns: poorly trained conscripts neglected basic tank care, failing to inspect reactive armor modules or replenish hydraulic fluids, resulting in dozens of tanks rendered combat-ineffective for trivial reasons.

Quantifying the Gap: Equipment vs. Personnel Spending

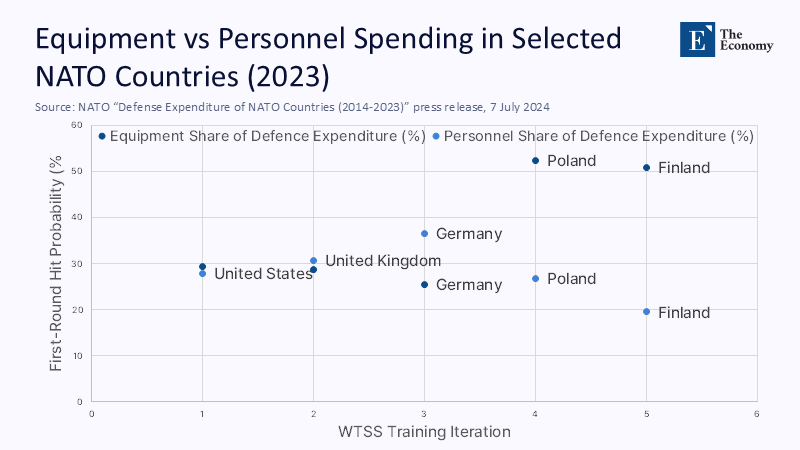

NATO’s budget breakdowns illuminate how allies value hardware relative to people. In 2023, member states’ average defence expenditure allocation was roughly 32% for equipment and 50% for personnel, with the remainder on operations and infrastructure. However, this average masks stark differences. As shown in Figure 1, Poland and Finland dedicate more than 50% of their defence budgets to equipment—52.4% and 50.8%, respectively—while spending just 26.7% and 19.5% on personnel. By contrast, Germany emphasizes human capital, allocating 36.6% of its budget to personnel—the highest among the surveyed nations—while investing only 25.4% in equipment. The United States and United Kingdom show more balanced spending, with approximately 30% directed to each category.

The scatter underscores a strategic imperative: each marginal euro in equipment must be matched with investment in training, leadership development, and soldier welfare. This is not just a matter of budget allocation, but a strategic necessity. Otherwise, diminishing returns set in as complex systems outpace their operators' cognitive and technical skills.

Building Battlefield Competence: Simulation and the Smart Soldier

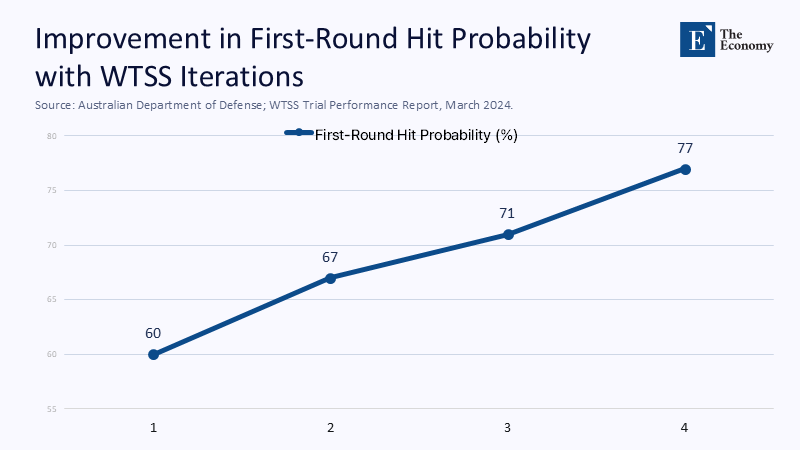

Faced with budget constraints and the need for rapid readiness, many militaries have turned to advanced simulation technologies to compress learning curves. Australia’s Weapon Training Simulation System (WTSS) exemplifies this trend. Instead of seven live-fire sessions consuming rounds, vehicles, and time, WTSS delivers equivalent marksmanship and tactics training in a 30-minute, sensor-rich virtual environment, reducing ammunition costs by 90%. The system’s telemetry captures every trainee’s shot placement, reaction time, and decision path, creating actionable feedback loops. An internal evaluation presented at the 2024 Defence Human Sciences Symposium reported that after four WTSS iterations, soldiers’ first-round hit probability jumped from 60% to 77%, with gains retained months later in live-fire testing. This is a clear demonstration of the potential of simulation technologies to revolutionize military training.

WTSS is part of a broader shift toward the “smart soldier”—one whose mind, not just muscles, drives advantage. This concept is not just a buzzword, but a fundamental shift in how we approach military training. The U.S. Army’s Engagement Skills Trainer and the U.K.’s Dismounted Soldier Training System perform analogous roles, while virtual reality modules now augment pilot and naval engineer training. These tools transform each training hour into high-impact learning, enabling troops to rehearse rare or dangerous scenarios safely and frequently. Importantly, simulations democratize access—reserve units or geographically remote formations can sustain proficiency without centralized ranges.

A Korean Anecdote: Tools Are Useless Without Talent

The importance of training over kit is not new. Between 2003 and 2005, South Korean conscripts regularly shared firing ranges with the U.S. Army stationed in Korea. The Americans arrived with state-of-the-art night-vision goggles, GPS systems, and computerized targeting gear that South Korean infantry lacked. Yet in field drills, Korean mortar and reconnaissance teams easily outperformed their counterparts. On one night exercise, a U.S. crew spent an hour debugging a digital fire-control module before reverting to manual methods—while the Korean crew, drilled on analog tables, delivered rounds accurately in minutes. Mechanics joked that a high-tech vehicle stuck in mud was less recoverable than a Korean Humvee with no electronic aids. South Korean soldiers quipped, “We mock that fancy American gadgets are useless without the training to use them—no wonder they struggled in Vietnam.” This refrain, lighthearted on the drill field, carried a sobering lesson: the human operator is the linchpin of military effectiveness. No tax-dollar gadget can compensate for a skill gap.

The Talent Conundrum: Attracting Tech-Savvy Recruits

Advanced simulation and training methods help, but Western forces face a deeper challenge: attracting and retaining the right people. Across NATO, demand for STEM-literate recruits in cyber, intelligence, and advanced weapons specialties outstrips supply. The U.S. Army missed its 2022 accession target by 25%, with the cyber workforce 24% below need. High private-sector salaries lure budding technologists away. Even when specialists enlist, many depart after initial tours, and the industry highly prizes their combat cyber skills. One senior officer lamented, “We’re training our replacements for Silicon Valley.”

Cultural factors compound the problem. Military life—still perceived as hierarchical and risk-averse—struggles to compete with the entrepreneurial ethos of tech startups. The Israeli Defence Forces, however, have successfully cultivated tech talent through prestigious units like 8200, where graduates emerge equipped to found companies before discharge. Western allies must emulate such models: creating clear STEM career tracks, offering flexible service options, and celebrating technological innovation within uniformed ranks. Otherwise, today’s fighter jets, described as “flying computers,” may sit grounded for want of qualified pilots and maintainers.

Lessons from History: Vietnam to Desert Storm

History repeatedly underscores the primacy of human factors. During the Vietnam War, the U.S. fielded superior firepower—B-52 bombers, helicopters, sensors—yet its short-term draftees, lacking language and jungle warfare training, struggled against an adaptive foe. Viet Cong fighters, steeped in guerrilla doctrine and terrain mastery, outlasted and outmaneuvered their adversaries. The U.S. military’s post-war reforms—professionalization, advanced training centers, and an all-volunteer force—stemmed from that painful lesson.

In the 1991 Gulf War, technology and training coalesced. Coalition forces deployed stealth fighters, smart bombs, and M1A1 tanks—yet these advantages mattered because crews had honed their craft through rigorous Desert Shield preparations. Iraqi tankers, by contrast, had minimal gunnery practice and immature combined-arms doctrine; analysts noted, “Iraqi crews couldn’t hit the broad side of a barn” despite similar armaments. The result was a swift victory with minimal coalition casualties—proof that proficiency, not just platforms, determines outcomes.

Policy Prescriptions: Re-Arming the Mind, Not Just the Arsenal

To translate these lessons into lasting defence policy, NATO and its allies should prioritize training, simulation, and human capital development alongside hardware procurement. Setting alliance-wide training benchmarks, investing in military education, and leveraging simulation technology would ensure that expensive equipment is matched by capable operators. Emulating models like Israel’s Unit 8200 to attract STEM talent and expanding cross-border simulation exercises would further enhance collective readiness. In essence, military spending must balance steel with skill—Europe’s arsenal must be as sharp in mind as it is in metal.

Re-arming the Mind

Europe’s rush to acquire advanced weaponry is understandable—no one doubts that tanks, jets, and missiles matter. But actual deterrence and battlefield success hinge on the minds behind the triggers, wheels, and joysticks. As South Korean conscripts long ago discovered, fancy gadgets without the training to use them are worthless—no wonder they jested that such gaps explain past U.S. difficulties in Vietnam. The Russo-Ukrainian war has vividly illustrated that poorly trained crews abandon their vehicles; well-trained soldiers exploit every system to its fullest. History, from Vietnam to the Gulf War, reinforces that a professional, educated, and adaptable force outperforms even a more heavily armed but less proficient opponent.

As drones, cyber operations, and AI-driven systems proliferate in the years ahead, the premium on human capital will only grow. Policymakers must resist the seductive simplicity of counting tanks and missiles without counting training days, simulation hours, cyber certifications, and leadership courses. Defence budgets should reflect this priority: personnel line items are not mere overhead, but the bedrock of military power. A fighter jet without a skilled pilot is a paperweight; a networked air-defence system without trained operators is a dangerous tech toy. Conversely, a well-trained, agile soldier corps can make do—and even excel—with less glamorous kit.

Modern deterrence is as much cognitive as kinetic. Those nations that cultivate cultures of continuous learning, invest in simulation and real-world training, and attract the brightest technical minds into uniformity will hold the true advantage. It is time to act decisively. Train harder, train smarter, and never forget that wars are won by human beings' will and intellect. The missiles and machines are along for the ride.

The original article was authored by Manuel Trajtenberg, a Research Associate at the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER). The English version of the article, titled "Human capital formation as a key component in Europe’s defence build-up,” was published by CEPR on VoxEU.