Input

Changed

This article was independently developed by The Economy editorial team and draws on original analysis published by East Asia Forum. The content has been substantially rewritten, expanded, and reframed for broader context and relevance. All views expressed are solely those of the author and do not represent the official position of East Asia Forum or its contributors.

The assembly lines of Bac Ninh and Binh Duong have produced an unlikely macroeconomic statistic: in 2024, Vietnam sold $123 billion more goods to the United States than it bought—a surplus almost double the imbalance that triggered Donald Trump’s first tariff broadside against Beijing eight years earlier. This single data point encapsulates Hanoi's urgency and potential risks. It demonstrates that the “China‑plus‑one” strategy multinationals adopted after the 2018 US‑China trade war has evolved closer to “China‑0.7”, with Vietnam absorbing ever larger shares of global electronics, furniture, and apparel production. Yet, this same number places a target on Vietnam just as a protectionist White House prepares a new schedule of across‑the‑board duties. For Vietnam, the next six months are a routine diplomatic challenge and a critical juncture determining its economic future.

From ‘China Plus One’ to ‘China 0.7’: Vietnam's Transformation into a Global Manufacturing Hub

From the ‘China Plus One’ strategy, where companies diversified their manufacturing bases to include countries other than China, to the ‘China 0.7’ strategy, where Vietnam has become a central manufacturing hub absorbing a significant portion of global electronics, furniture, and apparel production.

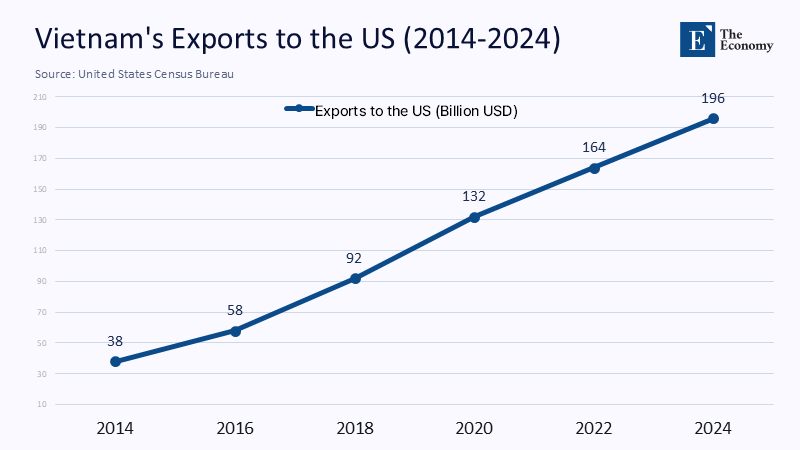

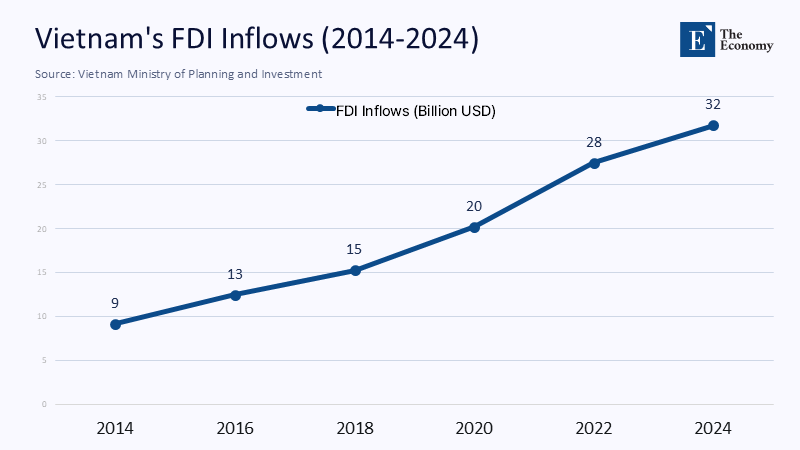

No emerging economy has compressed an industrial learning curve as aggressively as Vietnam. In 2014, the country shipped just $38 billion worth of merchandise to the United States; by 2024, that figure had vaulted to $196 billion—an 18% compound annual growth rate, three times the pace of China’s sales to America over the same period. Foreign direct investment provided the fuel: cumulative approvals crossed the half‑trillion‑dollar threshold last December, with two‑thirds flowing into processing and manufacturing. Samsung now assembles four‑fifths of its smartphones in Vietnam, Nike sources more shoes there than in China, and Apple’s supply chain has quietly commissioned ten new test‑production lines around Hanoi. The attraction has been straightforward: wages one‑third of those in the Pearl River Delta and preferential tariff treatment under the US Generalized System of Preferences. A growth spurt lifted Vietnam’s GDP by an average of 6.2% yearly through the pandemic. However, it also means Vietnamese prosperity is unusually influenced by external decisions made in Washington and Shenzhen rather than Hanoi.

Shadow Factories and the Limits of Camouflage

The “shadow‑factory” model worked only as long as it remained, in effect, shadowy. US Customs and Border Protection recorded a 310% surge in Vietnamese‑labelled containers that first cleared mainland ports before trans‑shipping through Hai Phong 18 months following the original Trump tariffs. Congressional staffers now routinely describe Vietnam as “China’s back door.” At the same time, the Hinrich Foundation estimates that 28% of the value added in Vietnamese electronics exported to America in 2024 was still Chinese. This is politically toxic in Washington, where the perception of tariff circumvention compounds the optics of a widening bilateral deficit. Once such a narrative hardens, it overrides technical truths about supply‑chain intermediacy. Just as Mexico became collateral damage in the 1990s NAFTA debate, Vietnam risks becoming shorthand for every shuttered factory in Ohio. Camouflage has therefore reached its limit; Hanoi must offer substantive reasons, beyond low labour costs, for the United States to treat it differently from China.

Counting the Cost: How a 25 % Tariff Could Shear Away a Year of Growth

The arithmetic is brutal. If the White House applies a uniform 25 % duty to Vietnam’s $196 billion in shipments, historical pass‑through studies suggest roughly half of that burden will fall on Vietnamese suppliers, given contract assembly’s paper‑thin margins. That translates into $24.5 billion lost revenue—about 6.1 % of national output. Add the knock‑on effects on port services, trucking, and consumer spending, and Vietnam could forfeit a whole percentage point of GDP growth in 2025. Employment elasticity estimates from the International Labour Organization indicate that every one percent contraction in manufacturing output costs 80,000 direct jobs. A tariff shock threatens half a million factory positions and doubles that number in supporting services. Domestic demand cannot fill the gap: household consumption is still only 60% of GDP and tilted toward agriculture. The upshot is clear—Vietnam’s growth model is leveraged to the US consumer, and any meaningful tariff will register on the national accounts with seismic force.

The Race to Replace—India, Indonesia, and the Elasticity of Supply Chains

Two decades ago, moving a plant required disassembling heavy tooling and retraining entire workforces; today, modular robotic lines and cloud‑based process control let assemblers decamp in months. That operational elasticity is Vietnam’s most immediate threat. Foxconn has leased two million square feet in Tamil Nadu, while Pegatron is doubling a $1.6 billion campus in Batam, explicitly citing “tariff diversification.” Wage data underscore why those alternatives tempt procurement officers: Vietnam’s average manufacturing wage reached VND 8.4 million (roughly $340) per month in early 2025, whereas comparable pay in India’s industrial belts is about $260 and in Indonesia, $280. Delhi sweetens the calculus with performance‑linked incentives worth up to 4% of smartphone export value. At the same time, Jakarta offers 20‑year tax holidays for investments above $1 billion and has cut factory‑connection times to the national grid to under 90 days, half of Vietnam’s average. In other words, the same cost‑plus‑policy cocktail that once lured production from China now threatens to siphon it away from Vietnam if tariffs erase the price edge.

Policy Pivot Required: From Cost Advantage to Value Advantage

Vietnam’s strategic response must begin by recognising that labour arbitrage is melting ice. Wage convergence with peers and investors’ new premium on supply‑chain resilience means that offering a cheaper factory floor is no longer sufficient. Hanoi must move up the “smile curve,” capturing value in design, R&D, and after‑sales services. The seeds of that transition already exist. Last year, Amkor inaugurated a $1.6 billion advanced‑testing plant in Ho Chi Minh City; Synopsys is training 4,000 local chip designers; and VinFast’s R&D campus is hiring aerospace engineers for electric‑vehicle battery innovation. Yet high‑tech exports excluding phones still represent only 6% of Vietnam’s total shipments, versus 21% in Malaysia and 28% in South Korea at similar stages of development. Government can accelerate the shift by offering super‑deductions for R&D, rolling out 5G industrial corridors, and—most importantly—enforcing intellectual‑property rights robustly. Vietnam’s 2023 accession to the Hague System for international design registration was a start, but court enforcement remains slow, deterring frontier‑tech investors. Closing that gap would allow Vietnam to brand itself not merely as the place where gadgets are assembled but where the next generation of gadgets is conceived.

Labour, Wages, and the Social Compact Hanoi Cannot Ignore

Moving up the value chain also demands a new social contract with workers. For decades, Vietnam kept statutory wage hikes a hair below productivity gains; that logic has reached political and economic ceilings. Industrial wages have risen 7% annually since 2019, outpacing productivity by nearly two points. At the same time, scrutiny of labour rights is intensifying. The full ratification of ILO Convention 87 on free unionisation is a condition for deeper EU market access under the EVFTA. Ottawa has already opened a dispute panel under the CPTPP over alleged violations. Failure to deliver tangible reform risks not only reputational damage but the loss of tariff preferences that still underpin apparel exports. Yet, properly managed, higher wages can catalyze automation and skill upgrading. South Korea’s experience in the late 1980s—when real wages doubled and forced conglomerates to invest heavily in robotics—suggests that rising labour costs, if anticipated, can propel rather than cripple competitiveness. Hanoi, therefore, should embrace steady wage growth as a mechanism to force capital deepening and productivity gains.

ASEAN’s Collective Stakes and the Opportunity for Regional Bargaining

Vietnam’s predicament reverberates well beyond its borders. ASEAN now supplies 17% of America’s manufactured imports, up from 11% in 2019, largely thanks to Vietnam’s surge. The region could lose its painstakingly built bargaining leverage if that wedge narrows sharply. Paradoxically, Vietnam’s vulnerability thus becomes Southeast Asia’s strategic opportunity: by forging a unified stance on supply‑chain traceability and digital customs clearance, the ten‑member bloc could offer Washington something Beijing cannot—transparent, multi‑country production networks that mitigate geopolitical concentration risk. Singapore’s Networked Trade Platform already provides end‑to‑end electronic documentation; extending that architecture to Vietnam, Indonesia, and Thailand would create a verifiable trail of origin and make tariff‑circumvention claims harder to sustain. Such integration requires political will and budgetary resources, but the alternative is fragmented bilateral negotiations with a US administration that has shown itself willing to weaponise trade statistics.

Diversifying Demand—From LNG Cargoes to Digital Services

Even the best‑designed ASEAN strategy cannot neutralise tariffs if the United States remains a single‑point failure in Vietnam’s export ledger. Diversification is therefore essential. PetroVietnam has inked long‑term contracts to import American LNG—a savvy gesture that narrows the bilateral deficit and secures cleaner energy for industry. Meanwhile, the EU‑Vietnam Free Trade Agreement lifted two‑way goods trade to €49 billion in 2024, and Vietnam’s e‑commerce market is on track to hit $40 billion by 2027. Services must carry more weight. By positioning itself

as a regional fintech sandbox and cloud‑computing centre, leveraging partnerships with AWS and Google Cloud already in pilot, Vietnam can generate tariff-insensitive export earnings. Accession to the Digital Economy Partnership Agreement, led by Singapore and New Zealand, would anchor those ambitions in rule‑making forums valued by Washington and Brussels alike, further dispersing external risk.

A Year That Will Feel Like a Generation

The clock now ticking on Hanoi’s policy deliberations is unforgiving. The US Treasury usually finalises tariff lists within six months of a new administration taking office; by then, most multinational procurement plans for 2026 will be locked. That means the substance of Vietnam’s response—labour reform, investment incentives, and supply‑chain transparency—must be enacted, not merely announced, before the 2025 Lunar New Year if it is to influence corporate site selection. Failure will not instantly unravel the Vietnamese growth story. Still, a slow bleed of incremental orders will begin, eroding cluster economies of scale, pushing investors toward India, Indonesia, and even reshoring options in Mexico. Conversely, success would cement Vietnam as the indispensable second pole in Asia’s manufacturing constellation, balancing China’s gravity while setting new standards for innovation‑driven, rules‑based growth. Therefore, what happens between now and December will echo throughout ASEAN for the next decade—a compressed economic pivot that will feel less like a policy debate and more like a generational turning point.

The original article was authored by Vu Lam, a Policy Analyst and Researcher affiliated with UNSW Canberra. The English version, titled "Vietnam faces the fallout of US trade volatility," was published by East Asia Forum.