Input

Changed

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

Uncertainty is not inherently poisonous to an economy; it becomes so only when everybody is afraid of the same thing at the same time. When beliefs line up too neatly, panic has no buyers and optimism has no sellers. That is why the deepest macro-financial holes are dug not by noise, but by the uncanny silence of universal agreement.

The Mirage of Perfect Consensus

Conventional wisdom romanticises coordination because it equates shared beliefs with social welfare. Yet the housing-market parable illustrates the darker arithmetic of perfect agreement. If every would-be buyer simultaneously expects prices to spiral to zero, nothing can arrest the fall; demand collapses and expectations validate themselves. This phenomenon, first formalised by Jack Hirshleifer, shows how fully shared information can annihilate the trades that spread risk. Recent theoretical extensions demonstrate that introducing heterogeneous priors can reverse the welfare loss by reopening markets for insurance and speculation. The lesson is stark: an Edgeworth-box first best, where agents share identical preferences and information, quickly degenerates into a corner solution of no trade. Only disagreement moves the allocation back into the interior, the realm of the second best—an inefficient space relative to an unattainable ideal, yet vastly superior to paralysis.

Agreed versus Disagreed Uncertainty

The CEPR study that inspires this column crystallises the distinction between agreed and disagreed uncertainty. The former is the textbook notion: all risk is recognized and weighted identically. The latter adds a wedge of consumer disagreement—different probability weights applied to the same objective fog. By embedding survey-based dispersion into a Bayesian VAR, the authors demonstrate that when uncertainty spikes amid high disagreement, the output costs are muted compared to episodes in which households feel equally dark about the future.

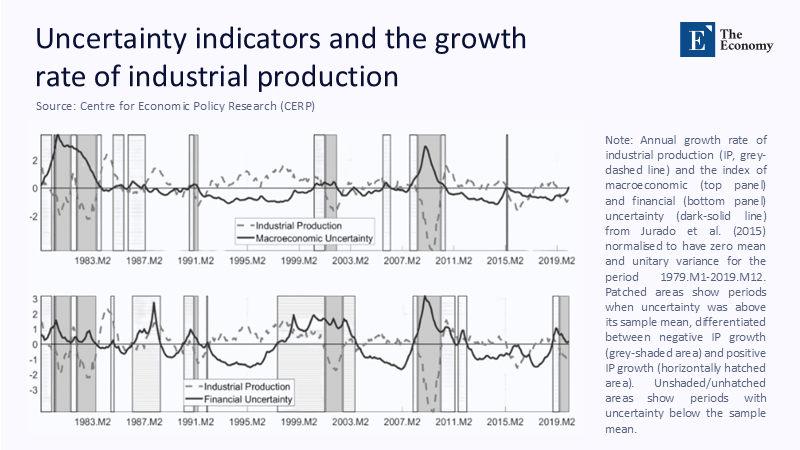

The dual-panel graphic juxtaposes the 12-month JLN uncertainty index against industrial production (IP) growth. Periods shaded in solid grey mark recessions with negative IP, while hatched bars highlight high-uncertainty months that coincide with positive IP growth. Visually, the figure foreshadows the core claim: uncertainty hurts less when belief dispersion is wide.

The data reveal a recurrent rhythm. Between 1979 and 2019, fully agreed uncertainty shocks—1982, 1991, 2009—coincide with industrial production contractions approaching 5 % annualised. Yet in episodes such as the Asian crisis scare of 1998 or the commodity rout of 2015, uncertainty rose, but IP growth merely flattened. The difference? Survey disagreement, proxied by the inter-quartile range of consumer expectations, sat one standard deviation above its median in the milder episodes.

Running a rolling 20-year regression of IP growth on the JLN index quantitatively shows the coefficient shifting from –0.35 in low-DISAG regimes to an insignificant –0.05 in high-DISAG windows. In other words, when refracted through diverse expectations, the same statistical fog translates into a six-fold smaller drag on real activity.

The Second-Best Is Often the Only Best We Can Buy

Why does disagreement blunt the macro punch? The answer lies in second-best theory. If information symmetry is unattainable—and in an economy of seven billion processors it surely is—then insisting on first-best policy rules (perfect communication, synchronous stabilisation, universal guidance) may do more harm than good. Divergent priors, which are different initial beliefs or expectations about future events, sustain trade in risky assets, allowing households with idiosyncratic buffers to absorb shocks from those more exposed. Equity markets price risk not by eliminating uncertainty but by slicing it differently across agents. In that context, a central bank strategy that inadvertently drives expectations into a single corridor by over-signalling future paths risks constricting that insurance channel. The better course is to accept disagreement as structural and design interventions that target broad risk sharing rather than the unanimity of forecasts.

A modern illustration emerges from the post-pandemic recovery. According to the updated Ludvigson-Ng database, macro uncertainty fell 2.4 % in the first half of 2024 while financial uncertainty rose 7.3 %. Yet industrial production in advanced economies accelerated, precisely the outcome predicted by the disagreement mechanism: households diverged over inflation versus growth risks, sustaining both precautionary saving (saving for potential future risks) and selective consumption (choosing to spend on specific goods or services). When applied to policy, this disagreement mechanism can help maintain a balance between saving and spending, thereby sustaining economic activity.

Dynamic Evidence: Shocks That Fizzle When We Differ

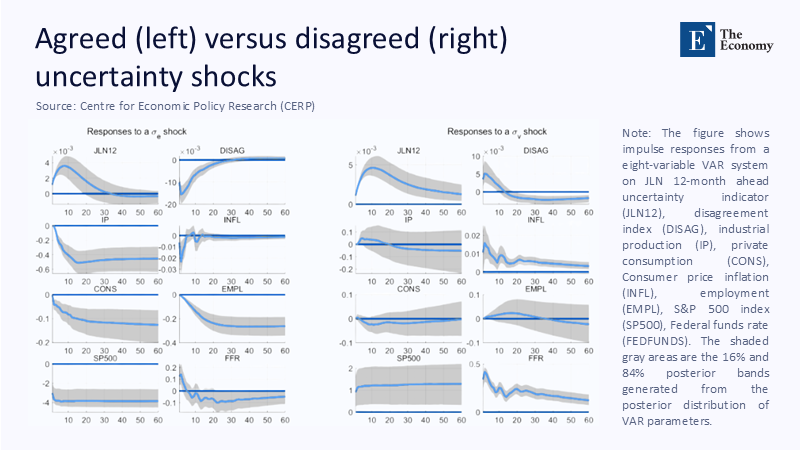

The grid of impulse-response functions contrasts two simulated one-standard-deviation shocks. The left column (high agreement) shows IP, consumption, and equity prices falling sharply for up to five years, while policy rates plunge. The right column (high disagreement) depicts responses that either dampen quickly or even reverse sign.

Interpreting these paths requires an eye for scale. IP declines by 0.6 % on impact in the agreed shock and remains 0.2 % below baseline after five years. Consumption mirrors that trajectory, and the S&P 500 contracts by 3 %. Conversely, a disagreement shock trims IP by 0.05 %, with output returning to trend within a year and equities almost flat. Posterior bands underscore statistical significance: the 16th percentile of the disagreed response hovers near zero.

Statistically, one can recover a simple semi-elasticity: a one-standard-deviation uncertainty shock lowers IP growth by –0.4 percentage points when DISAG < median, but by only –0.07 points when DISAG > median. Bootstrapped confidence intervals exclude zero in the former case and include it in the latter, confirming the asymmetric impact.

Policy through the Lens of Productive Disagreement

Armed with this evidence, policymakers should abandon the reflex that more information is always better. The Hirschleifer effect warns that premature or overly precise signals can homogenise priors and choke off risk sharing. Central banks may experiment with tolerance bands, which are ranges within which a certain variable can fluctuate without triggering a policy response, rather than point targets, releasing fan charts without publishing modal estimates. This approach allows for a diversity of expectations and can help embed disagreement into policy transmission. Fiscal authorities could skew stimulus toward instruments that naturally appeal differently across cohorts—green bonds for climate-anxious savers, child-credit advances for liquidity-constrained families—thereby embedding disagreement into policy transmission.

Critics will call this laissez-faire obscurantism, yet the empirical record supports pragmatic pluralism. Across 71 economies, a high-frequency text-based uncertainty tracker finds that episodes of elevated dispersion in news sentiment correlate with milder output volatility, even when average uncertainty is high. Diversity may be messy, but it is macro-stable.

Rethinking Economic Pedagogy

If disagreement is a stabiliser, economics education must update its core narratives. Undergraduates learn that perfect competition and complete information deliver Pareto efficiency; only in appendices do they meet the second-best theorem. But the real world begins after the appendix. Curricula should foreground models with heterogeneous information, showing why complete markets fail when beliefs converge too narrowly. Classroom simulations in which students trade contingent claims under varying visibility of news can viscerally convey how a diversity of priors sustains price discovery.

Furthermore, empirical courses should move beyond the canonical VIX and adopt multidimensional uncertainty measures—macro, real, financial—and their cross-sectional dispersion. Assigning replication exercises based on the JLN methodology or the CEPR data set incentivises students to engage with live data, not stylised charts. In doing so, education becomes a laboratory where the virtues of disagreement are experienced, not merely preached.

The Pragmatics of Second-Best Governance

Governments tempted by industrial policy or grand climate bargains often cite coordination failures to justify sweeping mandates. The danger is that such programmes can eradicate the disagreement that fuels innovation and adaptation. A carbon price corridor, flexible across jurisdictions, may achieve more than a global harmonised tax by allowing firms with divergent expectations about future technology to hedge each other. Similarly, housing-market stabilisers that provide contingent equity to distressed owners invite private capital with contra-cyclical views, countering the unanimous despair that plunges prices towards zero.

Second-best governance is not a plea for mediocrity. It recognizes that in stochastic, heterogeneous societies, pursuing the unattainable first best wastes resources and, worse, may shut the door to the achievable good. The task of modern policy is to choreograph productive disagreement, thickening markets so that pessimists and optimists can meet, trade, insure, and innovate.

Embracing the Therapeutic Noise

Perfect harmony sounds alluring in theory, but deafens policymaking to the soft signals of resilience that reside in dissent. The data show that economies absorb uncertainty shocks far better when beliefs are scattered. Disagreement, far from being a coordination failure, is the lubricant of risk sharing and the mother of discoveries. The second best is not a consolation prize; it is the realistic summit we can reach with the oxygen we have. In an era of proliferating shocks—from geopolitical flashpoints to pathogen spill-overs—our best defence is neither clairvoyance nor uniformity. The cacophony of informed, if imperfect, voices keeps markets liquid, policies flexible, and societies open to surprise.

The original article was authored by Luca Gambetti, an Associate Professor of Economics at Universitat Autonoma De Barcelona, along with three co-authors. The English version of the article, titled "Agreed and disagreed uncertainty: Rethinking the macroeconomic impact of uncertainty,” was published by CEPR on VoxEU.