Input

Changed

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

When nine out of ten endorsements hide their commercial strings, transparency becomes the costliest commodity in the digital marketplace. That single data point—an estimated 95 % of influencer posts on X that algorithmically qualify as sponsored yet carry no #ad or equivalent disclosure—captures the widening fault line between what regulators believe audiences need to know and what platforms incentivise creators to omit. It sets the stage for a policy arms race in which a subtler spear of “authentic” storytelling promptly pierces every new shield of disclosure law. The following analysis argues that static rules borrowed from twentieth-century broadcasting cannot contain twenty-first-century covert marketing; only a dynamic, data-driven disclosure infrastructure, coupled with sustained media-literacy investment, can shrink the gap between persuasion and informed consent, making continuous education a crucial component of the solution.

The Imperceptible Blur: When Content Morphs into Commerce

Influencer marketing has exploded from a $1.7 billion niche in 2016 to a $24 billion global industry in 2024, with forecasts of $32.6 billion by 2025. Yet that growth narrative obscures a simple asymmetry: the industry’s currency is authenticity, while its product is persuasion. In traditional advertising, the hard sell is obvious—sponsor logos, designated breaks, and formal disclaimers. The signal is diffused across morning skincare routines and unscripted apartment tours in social media feeds. Economic theory predicts this blurring because “credence goods” derive value from perceived independence; when an endorsement looks purchased, it depreciates. When creators earn up to $20,000 for a TikTok haul—an amount large enough to rival entry-level teacher salaries—concealing the transaction is not merely tempting but profit-maximising. Thus, commercialisation and camouflage rise, leaving viewers to decode relevance from resonance.

Education scholars note that such blurred persuasive environments erode critical-thinking transfer; if students cannot locate the boundary between experience and advertorial, they struggle to interrogate evidentiary claims elsewhere in the curriculum. The social cost is therefore pedagogical as well as economic.

Why Naturalness Breeds Non-Disclosure: The Behavioral Economics of Trust

Cognitive-psychology experiments on persuasion knowledge reveal that perceived naturalness significantly suppresses audience skepticism. When an Instagram post appears to be an impromptu selfie, viewers’ baseline trust is 25–30% higher than when the exact product is presented in a studio shot controlled for lighting and copy. These heuristics explain why disclosure rates remain stubbornly low despite a decade of policy exhortation. In 2024, the UK Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) received over 3,500 complaints about potential non-disclosure on social media, and its latest sweep found that roughly one-third of influencer ads carried no label whatsoever. EU regulators echo this pattern: a Commission “sweep” of 572 influencers revealed that 97% had posted commercial content, but only 20% systematically indicated it was advertising. The behavioural insight is stark: the closer a post mimics user-generated spontaneity, the less audiences expect a disclosure and the more costly that disclosure becomes for the creator’s engagement metrics. Rational influencers therefore under-disclose, and because detection probabilities remain low, expected penalties seldom outweigh expected gains.

Product Placement Lessons: Broadcast’s Transparent Illusion

Regulators often point to television’s sponsorship-identification regime as a model. EU broadcasters must display a “P” icon at program start, after ad breaks, and on closing credits. US stations comply with long-standing Federal Communications Commission rules mandating on-screen acknowledgement of any paid placement. Compliance is high because enforcement is centralised, distribution is linear, and failure is conspicuous—neglect to air the disclosure slate and millions of simultaneous viewers can complain. The online context, however, presents a stark contrast. Distribution is fragmented across billions of personalised feeds; disclosures, when present, vanish within expanding captions or rapid “story” frames; and enforcement agencies grapple with jurisdictional ambiguity. The comparison highlights a policy blind spot: product placement on linear TV is functionally transparent, not because the industry is inherently ethical, but because the medium’s architecture makes stealth infeasible. Social networks, by contrast, reward invisibility through algorithmic promotion of “native” content, effectively subsidising non-compliance. Treating these ecosystems analogously overlooks the structural divergence and underscores the need for innovative solutions to regulate influencer marketing in the digital age.

Regulatory Chameleons: The Digital Shield versus the Regulator’s Spear

In response to mounting evidence of covert persuasion, regulators have escalated rule-making. The US Federal Trade Commission revised its Endorsement Guides in October 2024, clarifying that ambiguous tags like #partner fail the “clear and conspicuous” test and setting penalties up to $51,744 per violation. Europe’s Digital Services Act (DSA) adds platform-level duties: huge online platforms must build searchable ad repositories and label paid content in legible formats, with fines reaching 6% of global turnover for non-compliance—a threat already levelled at X for deficient transparency tooling. National regulators are similarly sharpening their spears. The ASA’s May 2024 ruling against fitness entrepreneur Grace Beverley over six unlabelled fashion-brand posts reiterated that personal brands do not negate the obligation to declare a material connection. Yet every new rule spawns an evasion tactic: ephemeral Instagram “Close Friends” stories that vanish before auditors can screenshot; micro-influencer “link-in-bio” chains where sponsorship disclosure occurs off-platform; AI-generated avatars that present sponsored reels but lack a legal person to penalise. Enforcement thus lags innovation, and public-choice theory predicts it will continue to do so unless regulators switch from ex-post policing to real-time data co-regulation.

Quantifying the Invisible: Estimating the Social Cost of Hidden Ads

A rough welfare estimate underscores the stakes. If the influencer economy generated $24 billion in 2024 and empirical studies put undisclosed posts at 95 %, then roughly $22.8 billion in promotional spending reached consumers without an overt signal. Consume that undisclosed persuasive messages shift purchase intent by 3 % beyond what would occur with a visible #ad—consistent with meta-analysis effect sizes in native advertising research—and that average conversion value per $1 of influencer spend is $4 in downstream sales. The hidden-persuasion surplus extracted from consumers would approximate $2.7 billion annually: 24 billion × 0.95 × 0.03 × 4. That figure rivals public K-12 textbook budgets in several European countries, suggesting a material redistribution from unalerted consumers to brands. While the estimate is stylised, it illustrates that disclosure is not a mere formality; it mediates billions in welfare transfers. Equally important is the intangible cost to democratic discourse: when political micro-influencers deploy the same stealth tactics, the boundary between civic debate and paid messaging collapses, eroding deliberative integrity.

Toward a Dynamic Disclosure Infrastructure: Policy Recommendations

Regulation must therefore pivot from static checklist compliance toward adaptive, code-based governance. First, embed machine-readable disclosure metadata directly into platform APIs, enabling third-party auditors and researchers to flag real-time discrepancies. Second, mandate pre-publication risk scoring—akin to algorithmic content moderation—where high-reach posts mentioning brand keywords trigger disclosure prompts before posting. The DSA’s forthcoming industry codes of conduct, due in early 2025, provide a fertile venue for such technology commitments. Third, fines should be proportional to audience size multiplied by duration of non-disclosure, reversing the current incentive whereby micro-violations carry trivial penalties relative to exposure.

Fourth, integrate education policy: require curricular modules on digital advertising literacy from middle school onward, funded via a levy on platform ad revenues. Finally, pilot a public “ad transparency ledger” where disclosures are hashed to an immutable chain, ensuring that even deleted posts remain auditable. This architecture converts the elusive spear-and-shield duel into a more symmetric contest: regulators gain data speed, creators retain authentic storytelling, and platforms safeguard user trust.

Educating for Algorithmic Literacy in the Age of Covert Influence

The debate over whether undisclosed influencer content is “cheating” or simply “information sharing with commercial intent” misreads the problem. The ethical fault lies not in advertising—commerce has always relied on persuasion—but in knowledge asymmetry. Television solved that asymmetry with conspicuous product-placement icons visible to every viewer; social platforms, by design, dissolved such public squares into private corridors where disclosure can quietly disappear. Unless policy evolves from episodic crackdowns to systemic co-regulation—and education systems treat advertising literacy as core rather than ancillary—the invisible ad economy will continue to siphon attention, money, and agency from an audience that never granted informed consent. The real question is not whether undisclosed promotion can be stopped outright; history suggests a perpetual cat-and-mouse. The better metric is how small the informational gap can become, and whether our digital citizens graduate fluent enough to spot the difference between a recommendation and a revenue stream without waiting for a regulator’s belated intervention.

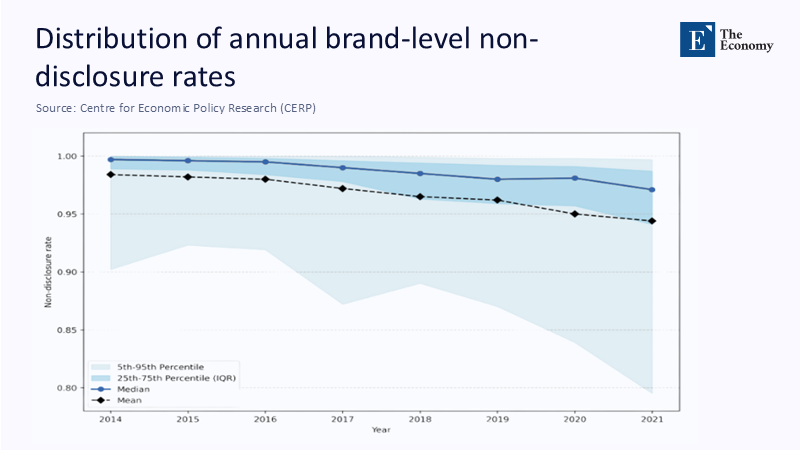

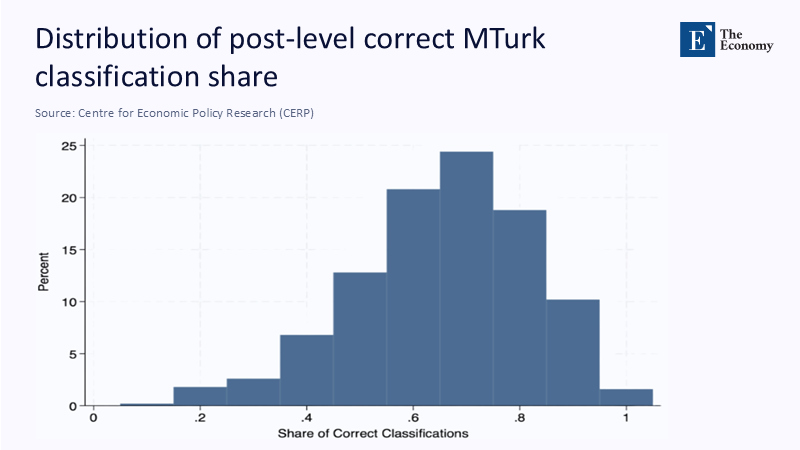

The original article was authored by Daniel Ershov, an Assistant Professor at the UCL School of Management at University College London, along with two co-authors. The English version of the article, titled "The majority of influencer advertising is undisclosed,” was published by CEPR on VoxEU.