Input

Changed

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

When a sovereign balance sheet swells to one-and-a-half times a nation's annual income, the red ink stops being a bookkeeping concern and becomes a veto on future choices. Greece's ratio of 153.6% of GDP at the end of 2024—the tallest debt mountain in the European Union—illustrates the point with brutal clarity: every program parliament debate must now pass an implicit solvency filter judged by creditors rather than citizens. The state's fiscal imagination collapses into a single preoccupation—maintaining market access—and the first casualty is long-horizon public investment in ports, research labs, and climate resilience, precisely the items that underwrite tomorrow's growth. This situation underscores the urgent need for reform in Greece's fiscal policy.

The Feedback Loop Where Credibility Devours Capacity

In orthodox models, a government can trade off speed and pain when consolidating its budget. In practice, bond markets rewrite the policy menu once the stock of obligations is perceived as unsustainable. Ten-year Greek benchmark yields hovered near 3.3% in mid-May 2025—about 120 basis points above the German bund—despite three consecutive upgrades to investment grade, evidence that investors still price a structural growth handicap rather than a liquidity hiccup. Each uptick in borrowing costs forces ministries to promise steeper primary surpluses; tighter surpluses sap aggregate demand and stall GDP; stagnation elevates the debt ratio, sustaining the risk premium. Credibility thus cannibalizes capacity: the more ferociously Athens pursues headline fiscal targets, the less room it leaves for the growth that would validate those targets ex-post.

Empirical Echoes from Italy's Two-Speed Trajectory

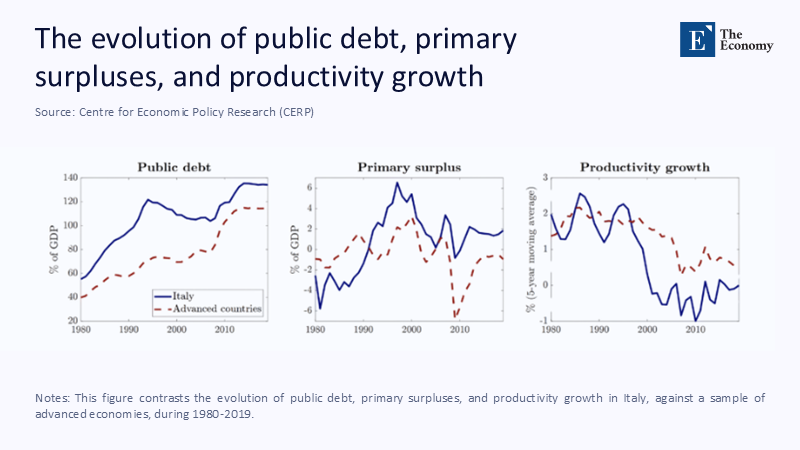

The syndrome is not uniquely Hellenic. Figure 1, reproduced from the CEPR fiscal stagnation study, tracks Italy's experience between 1980 and 2019. The blue solid lines show how public debt raced ahead of the advanced-economy average, while primary surpluses repeatedly swung above peers, yet multifactor productivity growth long before the Great Recession. The visual matters for Greece because it discredits the comforting claim that running large primary balances is enough to reassure markets. Italy's chronic belt-tightening, like Greece's post-2010 austerity, failed to offset the confidence drag from a persistently high stock of obligations. Instead, a high-debt economy must tax and save precisely when rivals invest and innovate, creating a two-speed union in which relative technological capacity deteriorates yearly.

An Investment Desert and Its Multipliers

Nowhere is that deterioration starker than in capital formation. Eurostat's functional classification puts Greek public investment just above 2% of GDP in 2024, compared with roughly 3% for the euro area. Combine that thin flow with a private sector still scarred by the crisis, and the aggregate gross fixed-capital-formation ratio has languished around 13% of output since 2010, fully nine points below the currency-union mean. A panel regression across EU members suggests that every percentage-point decline in public capital spending drags private investment down by roughly 0.3 points within two years, so the cumulative Greek shortfall has also shaved close to three points off the private investment ratio. The result is an "investment desert" visible in pot-holed provincial roads, under-scoped hydrogen corridors, and university engineering faculties short of lab equipment. The German Institute for Economic Research (DIW) estimates that the front-loaded consolidation of 2010-14, weighted by average multipliers of 1.3, accounts for almost the entire 25% peak-to-trough collapse in real GDP by 2015. Discounted at a social rate of 3%, the present value of lost output exceeds €400 billion—roughly twice the face value of the debt itself, a grim reminder that denominator effects can overwhelm heroic efforts to stabilize the numerator.

A Generation on the Move

Fiscal overhang does not just chase away investment; it depletes talent. The OECD reports that the emigration of tertiary-educated Greeks to other OECD members jumped 18% in 2022 to roughly 33,000, and Germany alone absorbed a third of the cohort. Domestic unemployment, headline-wise, looks healthier—8.3% overall and 20.4% among the under-25s in April 2025—but that improvement reflects demographic shrinkage more than job creation. When a country sheds both young workers and the firms that would employ them, the human capital channel locks in lower potential growth long after cyclical conditions normalize. Population projections already show head count slipping to below nine million by mid-century, which, on conservative assumptions, clips about half a percentage point off annual potential GDP even before accounting for skill composition. The vicious circle is plain: shrinking opportunity fuels outward migration; outward migration erodes the tax base; politicians facing a narrower base raise taxes or cut spending further, provoking another round of exits.

Simulating the Slide into Fiscal Stagnation

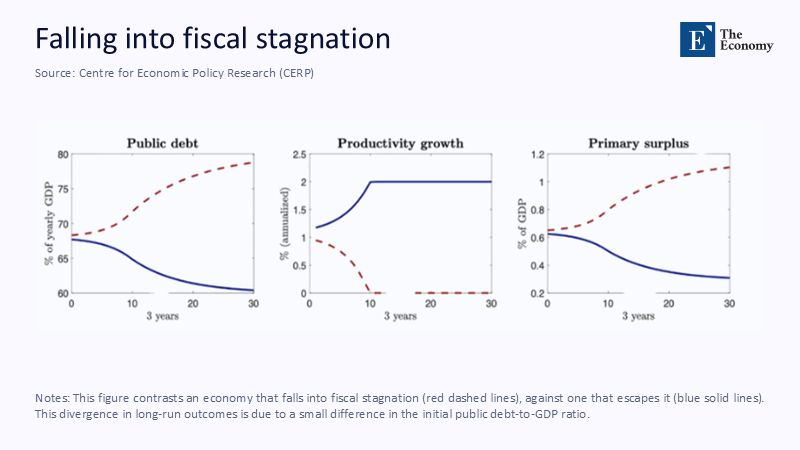

The mechanics above are captured elegantly in Figure 3, adapted from the same CEPR paper. Two economies identical in every respect, but their initial debt ratio diverge starkly over three decades: the one starting with a slightly higher burden (red dashed line) sees debt-to-GDP creep upward, productivity growth collapse to zero, and primary surpluses dwindle because revenue plummets; the low-debt twin (blue solid line) holds debt steady, enjoys a productivity updraft, and sustains moderate surpluses without punitive taxation. The lesson for policymakers is unforgiving: pass a threshold, and the macro system tips into a low-growth, low-investment equilibrium, even if headline deficits appear under control at the outset. Greece crossed that threshold around 2009; clawing back takes more than cosmetic surplus targets.

Comparative Latitude: Why Berlin Can Spend and Athens Cannot

Contrast that predicament with Berlin's 2025 volte-face. A long paragon of ordoliberal restraint, Germany secured a cross-party agreement for a multi-year infrastructure-and-defense surge, confident it could suspend the 0.35-percent structural deficit brake without inciting a bond-market revolt. Parallel discussions in Brussels about exempting defense investment from the re-made Stability Pact underscore how reputation creates de facto latitude: low-debt countries can breach ceilings temporarily because investors trust growth will return; high-debt peers, Greece foremost, dare not follow without seeing spreads explode. Reuters notes that EU finance ministers are mulling a four-year "defense fiscal holiday" to let well-rated sovereigns borrow outside the new rulebook. This option does not exist for Athens today. A monetary union that treats identical spending differently depending on the legacy debt stock effectively penalizes those whose growth needs a public investment kick-start.

Recalibrating the Fiscal Compass

Repairing credibility without throttling demand requires fiscal rules that breathe with the cycle. One workable redesign is a growth-contingent primary balance: the target would bind only when real GDP expands above 2%. That principle already resonates with the European Commission's 2024 guidance urging "growth-friendly" fiscal stances compatible with medium-term sustainability. Importantly, Greece's current arithmetic allows such flex. With ten-year yields at 3.3% and nominal growth projected near 4.5% for 2025-27, the interest-growth differential is negative, meaning debt would drift down as long as growth materializes rather than being choked off. IMF staff agree, arguing in the April 2025 Article IV that surpluses much above 2% of GDP would "undermine the investment-led recovery ."The key innovation, then, is to let automatic stabilizers and targeted capital outlays operate until growth exceeds the threshold—only then would the surplus ratchet up, aligning investor interests with expansion rather than contraction.

Toward a European Investment Buffer

Skeptics fear such flexibility invites fiscal laxity. Credibility, however, can be ensured. A dedicated EuroBuild facility—jointly capitalized by the European Investment Bank, the European Stability Mechanism, and the InvestEU guarantee—could trigger grants when a member's public investment dips more than one point below the euro-area rolling mean. Because the bonds financing EuroBuild would be joint, their yields should be priced near the EU's AAA curve, minimising carry cost for taxpayers. Eligibility would hinge on adopting the growth-contingent rule, ensuring that national authorities cannot game the system. The Commission's 2024 In-Depth Review already quantified Greek gross financing needs at around 8% of GDP across 2024-25; a pre-approved buffer of, say, 3% of GDP earmarked for green and digital infrastructure would cut that refinancing load nearly in half while delivering a direct demand impulse. By lifting the denominator of the debt ratio, such a mechanism makes creditors whole in expectation—a subtler but arguably safer form of conditional debt relief.

Restore Growth to Restore Solvency

After fifteen years of living under the weight of yesterday's promises, Greece shows with near-clinical precision that high public debt does more than constrain fiscal headroom; it corrodes the engine that generates tomorrow's tax base. The cost is measured not only in deferred maintenance or delayed climate projects but in discouraged graduates boarding flights to Munich and Amsterdam. Fiscal frameworks that automatically sacrifice productive investment on the altar of headline ratios deliver stagnation long before they deliver solvency. Replacing them with rules that make fiscal effort conditional on and supportive of real expansion, backed by a collective investment buffer, would turn Europe's most painful macro experiment into a blueprint for resilience. Until that shift occurs, high-debt states will continue to trade the prospect of shared prosperity for the mirage of immaculate ledgers, and investors will keep asking, quite rationally, "Who would lend to a country that strangles its future to pay for its past?"

The original article was authored by Luca Fornaro and Martin Wolf. The English version of the article, titled "Fiscal stagnation," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.

References

Bloomberg (2025). Greece Govt Bond 10 Year Benchmark – Quote GGGB10YR:IN, 16 May.

Deutsches Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung (2015). The Costs of Greece’s Fiscal Consolidation, Vierteljahrshefte zur Wirtschaftsforschung 3/2015.

European Commission (2024). Fiscal Policy Guidance for 2024. Press Release IP/23/1410.

European Commission (2024). In-Depth Review for Greece. Institutional Paper 281.

Eurostat (2025). Government Debt at the End of Q4 2024. Euro-Indicators, 22 April.

Eurostat (2025). Government Expenditure by Function – COFOG. Accessed 2 June.

Hellenic Statistical Authority via eKathimerini (2025). Only Five Out of Every Eight Women Are Employed, 30 January.

International Monetary Fund (2025). Country Data and Article IV Consultation for Greece, 7 April.

OECD (2024). International Migration Outlook 2024—Greece Country Note, November.

Reuters (2025). Merz Wins Support for Surge in Spending, Proclaiming "Germany Is Back", 14 March.

Reuters (2025). EU Eyes Tweak to Fiscal Rules to Allow More Defence Spending, 7 February.