Input

Changed

This article was independently developed by The Economy editorial team and draws on original analysis published by East Asia Forum. The content has been substantially rewritten, expanded, and reframed for broader context and relevance. All views expressed are solely those of the author and do not represent the official position of East Asia Forum or its contributors.

Stand on any busy street in Accra, Nairobi, or Kinshasa, and the statistical odds are better than one in two that the first lighted screen you see will belong to a Transsion handset powered by a Huawei-built cell tower and running a wallet whose transactions settle through Chinese cloud infrastructure. This is a coincidence and a result of a five-year vacuum in U.S. development finance. This vacuum has allowed Chinese vendors to align hardware, networks, and payments into a single policy funnel that now channels data, standards, and soft power away from Washington and toward Beijing. The urgency of the situation cannot be overstated.

A Funnel Built in Shenzhen: Devices as the New Diplomatic Passports

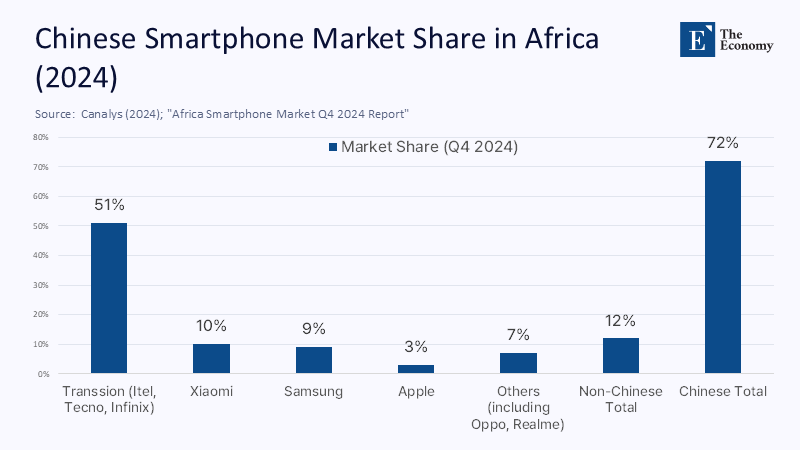

Africa's smartphone market is no longer a skirmish on the periphery of Big Tech; it is the fastest-growing pool of first-time internet users. In 2024 alone, shipments ticked up 6% year-on-year to 68 million units, with Transsion—parent of Tecno, Infinix, and Itel—commanding 51% of volume, more than Samsung, Xiaomi, Oppo, and Apple combined. This dominance is not merely commercial. Because most entry-level phones arrive with factory-installed Chinese app stores, browsers, and keyboards, Transsion has become the default curator of digital experience for roughly 250 million Africans. Its Swahili-optimized keyboards, low-light selfie cameras calibrated for darker skin tones, and dual-SIM power management are often examples of product localization; they constitute a subtle onboarding ritual into China's cloud ecosystem. Each firmware update pushes new services—music streaming from Boomplay (majority Chinese ownership), short-video apps seeded by Shenzhen VCs, and mobile wallets that bypass Visa rails in favor of QR standards first perfected by Alipay. Switching costs escalate sharply once a user's contact list, payment preferences, and entertainment history are captured. The handset becomes a diplomatic passport that stamps every interaction with a Made-in-China seal.

Networks and Norms: Infrastructure Written in Chinese Code

If devices grab attention, networks decide speed, latency, and which applications flourish. Dell'Oro Group's regional breakdown shows Huawei holding "over 50%" revenue share in the Middle East and Africa microwave and RAN segments for 2024, leapfrogging Ericsson and Nokia. Complement that with vendor-financed fiber backbones under the Export-Import Bank of China's US$700 million credit lines to the Africa Finance Corporation, and the result is an end-to-end stack where power budgets, antenna specs, and maintenance APIs all follow Chinese documentation. American export controls aimed at throttling Huawei's 5G ambitions have proved irrelevant in regions still monetizing 3 G and 4 G. For ministries juggling currency crises and debt restructurings, a 20-year concessional loan that bundles equipment, installation, and training is irresistible. Once installed, network software updates arrive from Shenzhen, not Seattle. In standards politics, the party that writes the firmware writes the rules.

Payment Rails and Behavioral Lock-In

The most intimate layer of dependency, however, lives in payments. Nigeria's licensed mobile-money platforms, PalmPay and OPay—both majority Chinese-backed—processed ₦71.5 trillion (≈US$50 billion) in 2024, a 71% jump over the previous year. Because the wallets ship pre-loaded on Transition phones, adoption curves look less like classic hockey sticks and more like auto-complete: tap once to accept terms of service, and a Chinese payment gateway occupies the home screen. Transaction data feed credit-scoring models hosted on Alibaba Cloud or Tencent's overseas regions, closing the loop between handset sales and fintech monetization. Importantly, the QR standards used by PalmPay mirror those of mainland China, not EMVCo, the global protocol stewarded by U.S. card networks. The longer Washington delays a secure, open alternative, the more likely future micropayments—from electricity tokens to school fees—will ride Chinese rails by default. In behavioral terms, every tap is a tiny referendum on whose norms govern Africa's data economy.

Surveillance and the Developmental Bargain

Critics often frame Huawei's "Safe City" camera grids as Orwellian exports. Yet, Bulelani Jili's recent work shows local police departments repurposing facial-recognition modules for homegrown priorities such as traffic management and border control. That flexibility, paradoxically, deepens dependence: upgrading analytics or adding license-plate recognition requires proprietary SDKs available only from original vendors. Municipal budgets that once bought stand-alone CCTVs now finance integrated data lakes whose dashboards integrate seamlessly with Huawei's FusionCloud. Unlike the Cold War-era practice of grafting American hardware onto Soviet infrastructure, substituting U.S. gear into a Chinese surveillance spine is technically arduous and fiscally prohibitive. Meanwhile, Chinese lenders sweeten deals with grace periods that coincide with local election cycles, giving incumbents both a short-term political win and a long-term technical shackle.

The Price of Retreat: USAID and the Hollowing-Out of Soft Power

None of this would have been inevitable had Washington maintained even a fraction of its 2010s footprint. Between 2020 and 2025, USAID's program portfolio shrank by 83% after a series of executive-branch rescissions—cuts confirmed by March 2025 congressional testimony. Digital learning pilots, broadband feasibility studies, and open-data fellowships—programs that once served as beachheads for U.S. vendors—vanished almost overnight. The gap was promptly filled by Beijing's Development and Cooperation Agency, which now hosts more African civil-service trainees in Shenzhen than USAID sends to Washington. The retreat also hindered Prosper Africa's ability to expand; its pharmaceutical-traceability pilot in South Africa is funded at less than US$5 million, a rounding error next to Huawei's annual R&D spend.

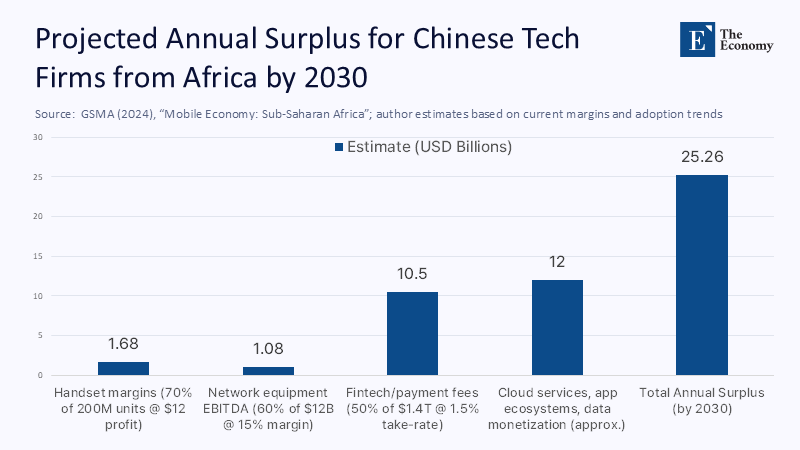

Quantify the consequences, and the numbers stagger. Assume, conservatively, that by 2030, Africa's digital economy will reach US$712 billion—a projection echoed in GSMA's latest Sub-Saharan report. If Chinese firms keep 70% of handset profits (US$12 gross margin per device on 200 million annual units), 60% of network-equipment EBITDA (15% margin on US$12 billion spent and 50% of payment-gateway fees (1.5% take rate on US$1.4 trillion in transactions), Beijing-aligned enterprises could net roughly US$25 billion per year out of Africa alone. This figure, which eclipses the entire FY 2024 State Department and USAID request for the continent, should raise serious concerns. Revenues are recycled into scholarship programs, think-tank grants, and lobbyists influencing procurement guidelines. Soft power, in short, is now a line item on someone else's income statement.

Reclaiming the Field: A Blueprint for Competitive Partnership

Reversing course requires more than rhetorical nods to a "rules-based order." First, Washington must weaponize its newest tool, the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation, with a dedicated US$10 billion digital infrastructure window—essentially a Marshall Plan for modems. Currently, the DFC site touts projects on everything from solar micro-grids to women-owned SMEs, yet offers no stand-alone facility for broadband or cloud interconnects. A ring-fenced fund could co-invest alongside African pension pools, crowding in domestic capital rather than displacing it.

Second, Congress should fast-track a Trusted Network Act that lets finance ministries factor long-tail security externalities—data sovereignty and lawful intercept protocols—into procurement. African regulators struggle to justify paying a 10% premium for U.S. or European equipment without explicit legislative cover.

Third, restore USAID's digital service corps. Instead of short-term consultants, embed American engineers inside African utilities for multi-year rotations, mirroring China's "Thousand Talents" exchanges. Field experience creates the social capital that concessional loans alone cannot buy.

Fourth, data reciprocity should be treated as market access. Offer African firms preferential entry to U.S. cloud regions if they adopt open-source encryption and transparent audit trails. This flips the script: sovereignty becomes a feature, not a cost.

Finally, fragmentary initiatives—Power Africa, Prosper Africa, and the Digital Transformation with Africa strategy—should be consolidated under a single deputy national security adviser for Tech Statecraft. Prosper Africa's tracking shows 401 facilitated deals worth US$32.5 billion in six months, but digital projects remain less than 8% of the pipeline. A unified chain of command would prioritize fiber corridors, landing stations, and regulatory sandboxes over donor-driven hackathons.

Counting the Missed Heartbeats

Soft power is rarely lost in a dramatic moment; it leaks, megabyte by megabyte, text by text, fare by fare. When a Tanzanian boda-boda driver tops up data on PalmPay or a Zambian school streams lessons over a Huawei router, a silent ledger records the transaction in yuan-denominated goodwill. Washington's decision to hollow out USAID and leave Prosper Africa undercapitalized turned that ledger into a structural deficit. Recovering the balance will demand hard choices: spending real money, accepting commercial risk, and acknowledging that policy is now written in firmware as much as in treaties. The window has not yet closed—Africa's smartphone penetration is only 51%—but every quarter of Transsion shipments, every mile of Huawei fiber, narrows the aperture. America once understood that influence begins with the first telephone pole and ends with the textbooks that ride the copper. In the age of cloud and QR codes, the principle remains unchanged, and it is not clear whether Washington can pick up its invented tools and start building again.

The original article was authored by Bulelani Jili, an incoming Assistant Professor at Georgetown University and a Visiting Fellow at Yale Law School.. The English version, titled "Africanising Chinese surveillance technology," was published by East Asia Forum.

References

Africa Finance Corporation & Export-Import Bank of China (2025) "Partnership to Drive Trade and Infrastructure Growth Across Africa."

Canalys (2024) "African Smartphone Market Expands Modestly by 6 % Amid Economic Headwinds."

CFR (2025) "Is China's Huawei a Threat to U.S. National Security?"

Dell'Oro Group (2025) "Emerging Markets Drive Microwave Transmission Revenue Up 7 % in 4Q 2024."

East Asia Forum (2025) "Africanising Chinese Surveillance Technology."

Foreign Policy (2025) "USAID Purge Ends With 83 Percent of Programs Canceled."

GSMA (2024) The Mobile Economy: Sub-Saharan Africa 2024.

Nairametrics (2025) "PalmPay, OPay Process ₦71.5 Trillion in Mobile-Money Transactions."

State Department (2024) "Digital Transformation with Africa."

White House (2024) "Celebrating U.S.–Africa Partnership Two Years After the 2022 U.S.–Africa Leaders Summit."