Input

Changed

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

When the compass that once guided global finance develops a barely perceptible tremor, every bearing calibrated to that compass begins to drift. Though initially unnoticed, this subtle shift carries significant implications for the global financial landscape, necessitating swift and decisive action.

Fitch’s decision in August 2023 to strip United States Treasuries of their triple-A imprimatur did not precipitate an exodus from the world’s deepest bond market, yet the symbolic loss was seismic. The rate against which virtually every other obligation is priced now carries an asterisk, and that asterisk behaves like a hidden tax on capital. Treasuries total about $27 trillion; a ten-basis-point risk premium, small enough to escape headlines, adds roughly $27 billion yearly to global interest costs. This cost propagates outward through financial mechanisms such as 'repo haircuts' (the reduction in the value of the securities used as collateral for a loan) and 'variation margins' (the additional collateral required to be posted by a party to a derivatives contract). For every basis-point change in the sovereign benchmark, IMF panel estimates suggest that private borrowing spreads respond by roughly one-third of a basis point; the downgrade extracts close to $30 billion a year from the cash flow of non-financial firms worldwide.

The silent welfare loss resembles a textbook dead-weight wedge: no legislature imposed it, and no taxpayer voted for it, but it shows up in tighter credit and forgone investment. In advanced economies where productivity growth already limps below 2%, that is a price few societies can afford.

The silent scramble for new anchors

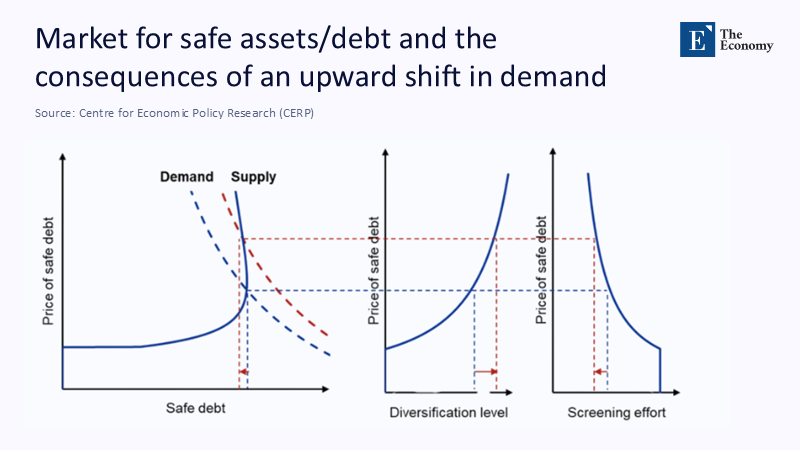

As public balance sheets strain, demand for liquid and default-remote assets keeps rising. Money-market fund balances hit a record of $7 trillion in early 2025, an unmistakable sign that institutional savers are parking cash wherever the collateral still feels iron-clad. Figure 1 sketches the core mechanics. When the demand curve for safety shifts outward faster than the supply curve can follow, the equilibrium slides sharply up the steep, right-hand segment of the supply schedule. Safe-asset prices jump, but because portfolios must balance, the same shift drives yields on everything else higher. The quest for safety makes the world less safe by ratcheting up costs for all other borrowers.

At this altitude on the curve, banks looking to meet relentless investor appetite face a choice between two imperfect instruments. They can widen diversification—pool ever larger bundles of heterogeneous loans and hope idiosyncratic risk averages out—or they can reinforce costly loan screening so that each underlying exposure becomes purer. The first strategy is cheap; the second is expensive. Markets, unsurprisingly, gravitate to the affordable option, expanding quantity while trimming quality at the margin.

The mirage of privately manufactured safety

Structured finance engineers have long promised that securitization can turn lead into gold. Layer enough subordination and excess spread, and the super-senior slice boasts a default probability that rivals a G-7 sovereign bond. Before the 2008 crisis, nearly 40% of all AAA-rated securities were privately issued. Today, the share is again climbing; ECB researchers calculate that securitization now covers roughly one-third of the global safe-asset gap, which they estimate at about $5 trillion.

Yet the alchemy comes at a cost. Because lower tranches insulate the super-senior note, the originating bank also structures, the lender’s marginal incentive to parse borrower risk falls. ECB evidence shows that each percentage-point increase in demand for private “safe” paper reduces average screening intensity by 15%, eventually shaving two-tenths of a percentage point from medium-term GDP growth. In other words, diversification becomes a substitute for due diligence; society inherits correlated tail risk instead of idiosyncratic defaults.

Private incentives and the social optimum

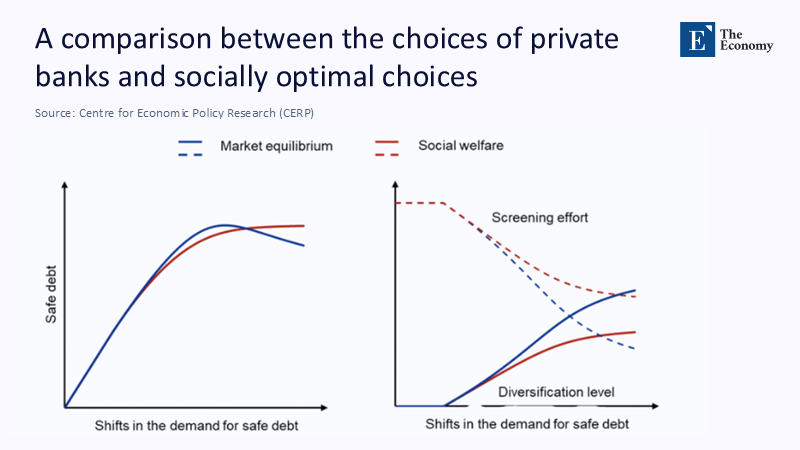

Figure 2 captures the divergence between individually rational and collectively efficient for banks. The blue line traces market equilibrium: as demand for safe liabilities climbs, banks churn out more securitized notes by pooling ever-broader portfolios. The red line traces welfare: once the marginal cost of systemic fragility exceeds the private benefit of additional issuance, society would prefer slower growth in quantity and a plateau in diversification, coupled with higher but costlier screening. The equilibrium overshoots the optimum on both dimensions because the originator bears the screening price while the collapse cost is dispersed.

This wedge is not merely theoretical. During the three quarters preceding the 2007 crunch, issuance of private AAA tranches rose 18% year-on-year even as underwriting standards deteriorated; when correlations spiked, the protective moat collapsed in lock-step. The lesson is stark: manufacturing absolute safety out of risky parts requires more than clever tranching—it needs governance that compels originators to internalize social costs.

Europe’s capital-markets union: a hybrid remedy

If the United States can no longer shoulder the entire burden of supplying pristine collateral and if pure market solutions embed latent fragility, the obvious candidate to step in is the European Union. The bloc’s households hold roughly €33 trillion in financial assets. Yet, the stock of undeniably safe euro-denominated paper—chiefly German Bunds and debt issued by supranational bodies—covers only a quarter of institutional demand. Brussels has, therefore, resurrected the Capital Markets Union (CMU) as a centerpiece of its post-2024 financial agenda.

The European Commission’s April 2024 “state-of-play” communiqué frames CMU not as a nice-to-have but as a prerequisite for financing the twin green-and-digital transitions. A parallel brief from the Jacques Delors Centre warns that tinkering on the fringes will merely ossify today’s fragmentation; only transformational reform—such as 'harmonized insolvency' (a unified set of rules and procedures for dealing with insolvent entities) and 'shared supervision' (a system where financial institutions are overseen by multiple regulatory bodies working together)—will bend the cost-of-capital curve.

Quantitatively, the prize is significant. If CMU doubled current securitization volumes to about €500 billion a year—still only one-quarter of U.S. flow—it could mint roughly €100 billion in new AAA-equivalent collateral annually. Couple that with the proposal to roll the temporary NextGenerationEU bond program into a perpetual “Blue Bond” of roughly €1 trillion outstanding. By the decade's end, the euro area could supply between one and one-and-a-half trillion euros of additional safe assets. At prevailing velocity in the repo market, each unit of top-quality collateral supports about ten units of secured funding, implying a potential €10 trillion expansion of low-risk interbank liquidity.

Such numbers translate into real-economy gains. Bank of Greece simulations indicate that a fully-fledged CMU could compress sovereign spreads for peripheral members by fifty basis points; for Greece, carrying roughly €400 billion in gross debt, that means €2 billion a year free for schools, hospitals, or climate resilience instead of interest coupons. This potential for significant savings and redirected funds towards societal needs offers a hopeful outlook.

The institutional architecture that still eludes Europe

Political rhetoric alone cannot bridge the incentive gap illustrated in Figure 2. Progress requires a triad of mutually reinforcing institutions, each more contentious than the last. It's crucial that all stakeholders, including policymakers, financial analysts, and economists, come together to address these challenges.

First, Europe needs a single, directly applicable insolvency regime. Divergent creditor hierarchies and recovery timelines add an estimated twenty-five to thirty basis points to cross-border securitization spreads. A model EU Insolvency Act, aligned with UNCITRAL principles and sponsored by a coalition of willing member states, would strip out that premium and standardize loss-given-default calibrations across the bloc.

Second, the supervisory perimeter must converge. At present, a securitization approved in one jurisdiction can be re-tranched elsewhere with only partial oversight—a loophole the Joint Committee of the European Supervisory Authorities flagged in its March 2025 review. Upgrading ESMA from coordinator to lead supervisor for cross-border special-purpose vehicles would erase the patchwork and prevent a replay of the “regulator shopping” that fuelled the 2000s CDO boom.

Third, a standing EU bond with its revenue stream is essential. Without an unambiguously safe public benchmark, securitization will again shoulder too much of the burden, inviting the incentive misalignments that Figure 2 condemns. Capital markets history suggests investors reward size and liquidity: a €1 trillion Blue Bond priced even five basis points through the Bund curve could shave half a billion euros a year off aggregate euro-area interest costs compared with pro-rata national issuance while anchoring the entire euro derivative complex.

None of these reforms is technically complicated; each is politically fraught. Insolvency unification trespasses on centuries-old legal traditions; shared supervision narrows national prerogatives; a common bond stirs fears of covert fiscal mutualization. Yet the opportunity cost of delay is mounting. Every six months of inaction perpetuates the funding premium that chokes high-growth sectors and keeps European venture capital volumes at barely a fifth of U.S. levels.

Three trajectories to 2030

In the base-case “status-quo drift” pathway, Treasury spreads remain ten basis points wider than their pre-downgrade baseline, while Europe executes only incremental CMU tweaks. Safe-asset supply grows at roughly 2% a year, well below demand. IMF term-premium models suggest the resulting rise in global funding costs would skim about 0.3% off cumulative world output by 2030, the equivalent of erasing the entire economy of Portugal.

A second pathway, “private surge, public stasis,” sees banks in both hemispheres compensating for stagnant sovereign issuance by accelerating securitization by 8% yearly. Spreads tighten briefly, but tail-risk metrics such as bond-portfolio value-at-risk climb 15% compared with the baseline. The next systemic shock would wipe out the accumulated savings, replaying a familiar boom-bust script.

Only the third pathway, “integrated CMU with an EU-level backstop,” breaks the trade-off. Here, harmonized law, single supervision, and a perpetual Blue Bond lift safe-asset growth to 6% annually, two-thirds public and one-third private. Empirical pass-through estimates put the reduction in SME borrowing costs at around sixty basis points; macro models indicate euro-area investment could rise by nearly three-quarters of a percentage point of GDP each year without increasing systemic risk.

Re-anchoring global finance

The downgrade of U.S. Treasuries reminds the world that even the most sacrosanct benchmarks are contingent. Attempting to patch the hole with ever more intricate private structures merely postpones and potentially amplifies the reckoning. Europe’s Capital Markets Union offers a rarer, more durable fix: combine scale—through a genuine pan-European bond—with governance—through harmonized insolvency and single supervision and elasticity via transparent, high-quality securitization. That architecture creates a multi-pillar compass: when one bearing wobbles, the others hold.

Rebuilding such a compass demands political capital today. Still, the alternative is to drift into a world where “risk-free” becomes an anachronism and every credit decision carries an invisible surcharge. In a low-growth, high-uncertainty era, that is a surcharge the global economy can ill afford.

The original article was authored by Madalen Castells-Jauregui, a Senior Economist at the European Central Bank. The English version of the article, titled "Private safe asset supply and financial instability," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.

References

Castells-Jauregui M., Kuvshinov D., Richter B. and Vanasco V. (2025) “Sectoral Dynamics of Safe Assets in Advanced Economies”, Working Paper, Bank for International Settlements

European Central Bank (2025) “Private Safe-Asset Supply and Financial Instability”, ECB Research Bulletin, 27 May

European Commission Directorate-General for Financial Stability (2024) “Capital Markets Union: State of Play—Looking Forward”, 10 April

Fitch Ratings (2023) “Fitch Downgrades the United States’ Long-Term Rating to AA+”, Press Release, 1 August

International Monetary Fund (2025) Global Financial Stability Report, April: Tumultuous Markets, Chapter 1

Jacques Delors Centre (2024) “Capital Markets Union: Europe Must Stop Beating Around the Bush”, Policy Brief, 11 July

Reuters (2025) “Money-Market Fund Assets Hit Record $7 Trillion as Investors Seek Safe Havens”, 5 March