Input

Changed

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

When the Berlin Wall crumbled, television cameras lingered on the concrete. Still, the decisive frontier lay in a spreadsheet column: an invisible gap of roughly €35 of value added per labor hour between Dresden and Dortmund. Three decades later, every credible growth story—from Shenzhen's hardware corridors to Tallinn's digital state—turns on how quickly societies compress such hidden frontiers. Therefore, East Germany's vertiginous leap in productivity remains less odd than a controlled experiment in modern development economics. Once we reinterpret that experiment with fresh data and visual evidence, one blunt lesson emerges: productivity is the only border that matters, yet the institutional fuel required to cross it cannot be bottled and exported at will.

The Productivity Principle, Quantified

Labour-hour productivity explains nearly three-quarters of long-run income variance across the OECD; capital deepening and demography trail far behind. The metric accounts for about 80 % of the GDP gap within Germany, which still separates Saxony from Bavaria. East Germany's sprint is thus remarkable not because GDP rebounded—most post-socialist economies clocked headline growth—but because efficiency exploded: output per worker jumped from 43 % of the western level in 1991 to 73 % by 1996 and hovers near 85 % today. Converting a thirty-point differential in five years is mathematically equivalent to sustained annual productivity growth six percentage points above the advanced-economy norm, a feat usually reserved for post-war reconstructions. The axis of convergence is, in short, an axis of efficiency.

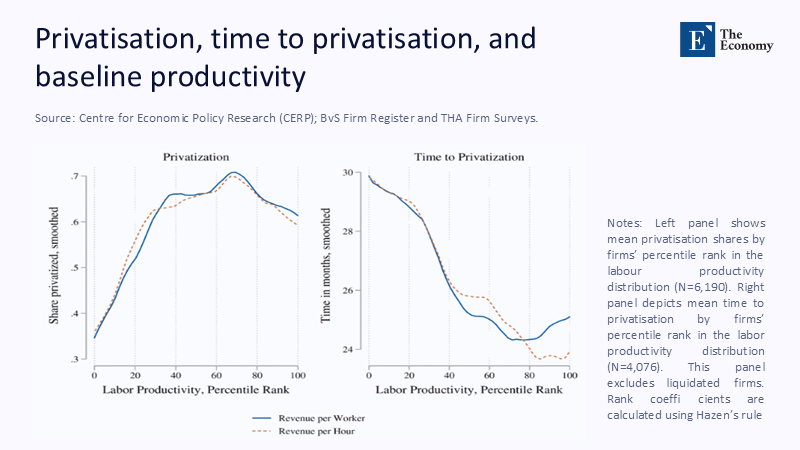

But abstract ratios can feel bloodless. Figure 1 grounds the narrative. The left panel plots the share of East German firms privatized by the Treuhandanstalt against their pre-transition productivity percentile; the right panel shows how long those firms waited for privatization. Two strategic decisions leap out: first, Treuhand officials prioritized mid-to-upper-quartile plants, sending the privatization rate above 65 % for firms already in the 40th to 70th productivity percentiles; second, better-performing plants exited public ownership fastest, shaving almost six months off the queue once they crossed the 50th percentile. In effect, the state bet on productivity leaders, and those leaders gained earlier access to new management, fresh capital, and hard budget constraints—all accelerants for the aggregate leap we observe in the national accounts.

Anatomy of a Leapfrog: Capital, Skills, Subsidies

How did the former GDR turn that front-loaded bet into a national surge? Three mutually reinforcing flows dominated: capital transfusions, skill migrations, and fiscal transfers. Between 1990 and 1995, more than 6,000 Western firms snapped up Treuhand assets, importing machine-tool vintages two technology generations ahead of local stock. Micro-studies of metal-fabrication plants in Chemnitz report total factor productivity (TFP) jumps of 9–12 % within eighteen months of western takeover, double the average for European brown-field acquisitions. Skills followed capital: 1.5 million west-to-east secondments in the 1990s raised the local stock of Meisterbrief technicians by 23 %. And the state underwrote the whole venture with an eye-watering €2 trillion in net fiscal transfers over three decades—roughly one-quarter of Germany's 2024 GDP—financing six-lane autobahns, factory-floor fiber, and energy-price equalization.

However, the region's success was not solely due to its economic firepower. The presence of institutional complementarity was equally crucial. Property rights, technical curricula, and commercial courts were effectively cloned from Bonn and rolled out east within eighteen months. Because licensing contracts and apprenticeship certificates were instantly recognizable, lean-production protocols were seamlessly integrated into shop-floor routines. This starkly contrasts the experiences of Polish and Hungarian investors, who still faced patchwork statutes that added two to three points of risk premium. Therefore, East Germany's success is a cautionary tale against geographical determinism: a generous neighbor is useless if the recipient lacks the institutional plumbing to absorb complex supply chains.

When a Currency Becomes an Accelerator

A second catalytic moment arrived with the euro. Monetary union removed exchange-rate volatility across a market of 300 million consumers, slicing trade costs by 4–6 % for second-wave adopters such as East German suppliers. Gravity-model decompositions reveal that intermediate-goods exports from Saxony and Thuringia to euro-zone assembly hubs outpaced pre-euro trends by ten percentage points during 2000-2008, the window in which the productivity gap narrowed most visibly. Crucially, firms had already breached the 70% productivity threshold; the euro amplified returns on new investment and served as a powerful accelerator for productivity growth. Currency unions can be silver bullets only when real-economy fundamentals are loaded in the chamber.

From Machine Tools to Microchips: Clusters as Productivity Flywheels

The initial leap rested on metal-working, but sustaining momentum required a pivot into higher value chains. Dresden's "Silicon Saxony" illustrates the compounding logic. Early fabs by AMD and Infineon seeded a semiconductor ecosystem that now employs 70,000 workers across 400 firms. A €10 billion joint fab spearheaded by Taiwan's TSMC and subsidized under the EU Chips Act is slated to add 40,000 wafer starts per month by 2027, each fab job generating roughly €350,000 in gross value added, three times the national manufacturing average. This strategic investment in high-value chains boosts productivity and inspires the potential for economic growth.

The same dynamic animates the electric-vehicle corridor from Leipzig to Brandenburg. CATL's Arnstadt battery plant, designed for 14 GWh capacity, has begun hiring engineers at a 28 % wage premium over regional norms. Fraunhofer spill-over models estimate that each gigawatt-hour of localized battery capacity lifts regional productivity by €110,000 per worker per year. Clusters, once seeded, become flywheels: supplier density trims input volatility, labor pools nourish learning-by-doing, and university linkages fast-track incremental innovation. Marshall's 19th-century insight about industrial districts remains intact in the deep tech era.

Counterfactuals Matter: Why Poland and Hungary Could Not Replicate the Sprint

The post-socialist bloc would float at German levels if proximity to rich neighbors and structural funds guaranteed success. Yet Poland, Hungary, and the Czech Republic, despite enviable GDP growth, still log labor productivity 25–30 % below the EU-15 average. Transfers were smaller—cohesion-fund allocations to the Visegrád quartet totaled about €150 billion, under one-tenth of the East German package. Legal convergence lagged: insolvency proceedings in Budapest take 1.8 years versus six months in Germany, depressing recovery values and inflating borrowing costs. And migration ran the wrong way: Warsaw lost two million degree-holders to Schengen's core just as East Germany imported Western skills. Productivity gaps are path-dependent; choose the wrong trajectory early and need more than tariff reductions to return.

Survival of the Fittest: What the Micro Data Say

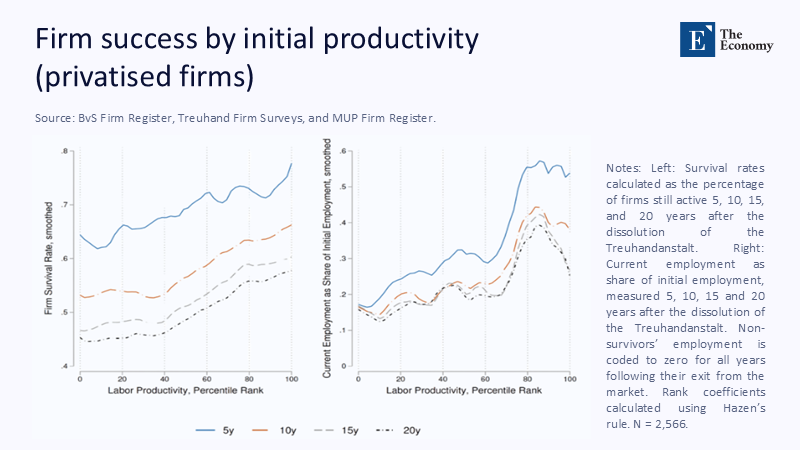

Aggregate numbers risk hiding selection bias. Fortunately, the Treuhand archives allow us to follow firms longitudinally. Figure 3 plots survival rates and subsequent employment as shares of initial headcount for the same 2,566 privatized firms, arrayed by baseline productivity percentile. Survival probabilities five years after privatization climb steadily from 58 % in the bottom decile to nearly 80 % in the top decile; twenty years out, the gap still exceeds fifteen percentage points. Employment dynamics tell an even sharper tale: high-productivity plants not only survive but add staff, with current employment reaching 55 % of pre-privatization levels in the top decile versus barely 20 % in the bottom. Productivity, in short, is destiny at the micro level.

These patterns confirm that Treuhand's bias towards the upper-middle of the productivity distribution was no accident: betting on firms already equipped with adaptive capacity created a higher-velocity rebound and, crucially, limited fiscal leakage into zombie enterprises. Policymakers elsewhere tempted by catch-all bail-outs would do well to scrutinize the selection filter implicit in Figure 3.

The Replicability Dilemma: Could a Greek–Turkish Axis Succeed?

Skeptics note that few regions enjoy a benevolent neighbor willing to tolerate multi-year negative growth while financing someone else's industrial reboot. West German GDP contracted or stagnated five times in the first eight years after reunification as the capital migrated east. Would Ankara bankroll Athens—or Athens, Ankara—under similar conditions? Political economy says no. Both electorates recoil at domestic austerity, never mind cross-border subsidies. Institutionally, the gap remains yawning: Turkey scores 0.55 on the World Bank's 2024 Rule-of-Law index, Greece 0.65, Germany 0.90. That delta translates directly into a higher cost of capital. Even within the euro, Greece's bid to raise productivity by legalizing six-day workweeks has triggered union resistance and may merely stretch hours rather than improve output per hour. Geography, then, is no substitute for legal and social scaffolding.

Toward a Productivity-First Industrial Policy: Design Principles

Because the German template is only partially portable, reformers must distill its essence. First, adopt conditional co-investment: public money should unlock only when firms hit auditable productivity milestones. Dresden's latest chip subsidy tranches are released once defect rates fall below defined thresholds—a metric investors and taxpayers both understand. Second, skilled labor flows should be treated as policy variables. Convergence slowed once east-west wage differentials shrank and migration reversed; Brandenburg now actively recruits Polish engineers for Tesla's Grünheide gigafactory, re-creating the 1990s arbitrage in a new guise. Third, any industrial push should be embedded in the green transition. Hydrogen, batteries, and carbon-neutral chemicals promise scale and margin; a clean-tech cluster doubles as a productivity engine. Fraunhofer channels €800 million annually into hydrogen and climate-neutral process industries precisely because decarbonization is also an efficiency dividend. Finally, resist blanket subsidies. Intel's delayed Magdeburg project and Wolfspeed's struggles in Saarland are cautionary tales: indiscriminate largesse can freeze capital in low-margin limbo rather than catalyze dynamic clusters. The litmus test is brutally simple: scrap it if a euro of public outlay cannot be linked to a predictable rise in value added per hour.

Playbooks for Small Open Economies

What about countries without West Germany's fiscal gunpowder? They can fabricate "synthetic proximity." Estonia's e-governance stack compresses compliance costs for mergers to EU-core medians, enticing capex that would otherwise ignore a market of 1.3 million residents. Costa Rica's life-sciences hub shows a parallel maneuver: vocational curricula aligned with ISO-lab standards reassure investors that small scale need not mean shallow talent. For emerging-market democracies, rule-book credibility substitutes for deep pockets: World Bank enterprise surveys reveal that halving contract-enforcement times accelerates firm-level productivity growth by two percentage points, often cheaper than tax holidays. Capital, ultimately, is allergic to uncertainty; remove it, and you buy productivity.

The Border Ahead

East Germany's tale is not a fairy tale but an algebra-plus institution. Technology, skills, public resolve, and credible legal frameworks—sequenced in that order—shifted an economy from command-and-control to near-frontier performance in a single generation. Yet the same narrative cautions against cargo-cult replication. The miracle hinged on an unusually patient donor and lightning-fast institutional osmosis. Nations charting their growth trajectories should begin by mapping the unseen border that runs through their factories, courtrooms, and classrooms. The Wall that still divides economies is made of productivity differentials and is as unforgiving as concrete.

The original article was authored by Moritz Hennicke, a Postdoctoral Researcher at the University of Bremen, along with two co-authors. The English version of the article, titled "Industrial policy lessons from East Germany's privatisation," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.

References

Bruegel. Eastern Germany's New Growth Engine (2019).

Destatis. "Gross Domestic Product: Detailed Results on Economic Performance" (Press Release 02/2025).

European Central Bank. "The Euro's Trade Effects" (Working Paper 594, 2024 update).

Fraunhofer-Gesellschaft. Impact of Fraunhofer Research (2022).

Fraunhofer-Gesellschaft. “Fraunhofer Strategic Research Fields” (2025).

Halle Institute for Economic Research (IWH). Press Release 14/2025.

Le Monde. "Germany's Postponed Microchip Plant Projects Cast Doubt on the Merits of Subsidies" (7 Sep 2024).

Guardian. "Greece Introduces 'Growth-Oriented' Six-Day Working Week" (1 Jul 2024).

European Commission / Eurostat. "Productivity Trends Using Key National Accounts Indicators" (March 2025).

CATL. "CATL in Figures" (Corporate Factsheet 2024).

Energy-Storage News. "Nearly All Gigafactory Projects in Europe Face Delay while CATL Announces Second Facility" (2023).