Input

Changed

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

The standard opening boast of many platform-based field experiments goes like this: “With 250 million active users, our randomized trial is adequately powered and representative.” What that declaration forgets is the pool from which those users are drawn. A study can randomize who sees a prompt, but not who volunteers for the platform in the first place. Today, 5.31 billion social-media identities exist—an impressive 64.7% of humankind—but that headline hides two stubborn facts: almost 2.9 billion people still use none of the major networks, and duplicate or underage accounts inflate the denominator of those who do. The result is an epistemic blindfold: researchers measure what happens inside a digital garden whose gates one-third of the world never crosses.

The illusion of universal reach

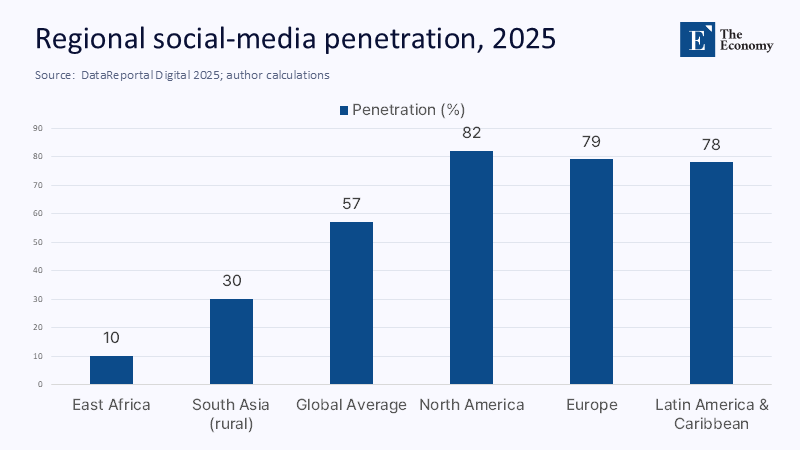

When platforms convert raw user counts into global reach using their dashboards, they perform a sleight of hand. A platform’s ad manager may brag about “audiences” that exceed local census tallies. Yet, in Ethiopia—the second-most-populous nation in Africa—the share of residents linked to any social media identity in January 2025 was just 6.2%. Across eastern Africa, median penetration still hovers below one in four adults; in parts of rural South Asia, it remains under one-third. Even in the United States, the Pew Research Center reports that 45% of adults aged 65 and older do not use any social platform, compared with just 6% of adults under 30. Therefore, treating platform users as a stand-in for the citizenry bakes inequity into research from the outset: whole regions, age groups, and income brackets vanish from the sampling frame before a single treatment is assigned.

Cartography of the Hidden Half

Digital divides are often caricatured as a binary—online versus offline—but closer inspection shows at least four overlapping chasms. First comes infrastructure: 78% of Ethiopians remained offline in early 2025 because the fiber and 4G still concentrated in a handful of cities. Second is affordability: mobile data costs in low-income countries can consume up to 7% of monthly earnings, triple the rate in high-income economies. Third is device mismatch: entry-level smartphones, common in rural markets, cannot render duplicate interactive content as the flagship handsets for which most experimental interfaces are designed. Finally—and most pertinently for field experiments—there is motivational distance: even when infrastructure and devices are available, users who stay off social media often cite concerns about privacy, harassment, and time drain. By definition, these non-joiners possess behavioral traits that correlate with the outcomes social science tries to predict: trust, attention, and compliance.

The double helix of bias

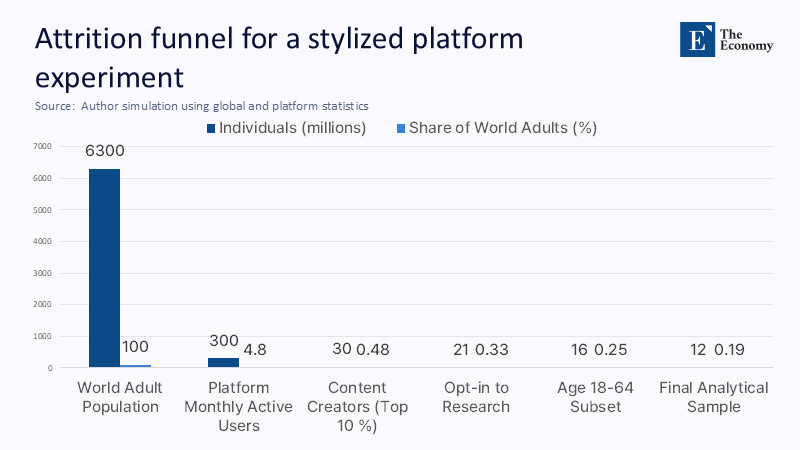

Bias, therefore, occurs twice. Selection bias arises because platform members differ systematically from non-members. Participation bias, which is the tendency for a minority of highly engaged users within the platform to generate the majority of content and to be likelier to opt into experimental modules, then compounds the problem. A 2023 study in EPJ Data Science demonstrated that on X (formerly Twitter), the demographic skew of people who post about gun control runs in the opposite direction to X’s overall user base. In other words, even if researchers weigh for age, gender, and ideology at the platform level, topic-specific engagement can still tilt results. The well-powered “N = 10 million” often heralded in methods sections may describe a hyper-vocal fraction representing less than 0.2% of the world’s adults.

Quantifying the abyss: a thought experiment

Consider a stylized anti-misinformation trial run on a platform with 300 million monthly active users to see how quickly representativeness implodes. Global data show that roughly 80% of those users live in upper-middle- or high-income economies, although only 44% of the world’s population does. That alone halves coverage for the rest of the globe. If 10% of users create 90% of posts, and opt-in rates to research follow a similar pattern, the adequate sample shrinks to about 30 million. Now, apply age-related consent gaps: among users over 65, only a quarter opt-in, compared with two-thirds of those under-30s, leaving roughly 12 million adults in the final analytical sample—just 0.19% of the global adult public. No amount of internal randomization can repair the hole that selection tears in external validity: power survives, and generalisability dies.

When evidence travels poorly: real-world misfires

Policy history offers cautionary tales. During the COVID-19 vaccine rollout, Facebook tested a Spanish-language information banner that lifted click-through rates by eight percentage points among U.S. Hispanics on the platform. Influenced by the headline effect, public health agencies in Bolivia helped fund a trans-Andean replication, only to discover that rural municipalities, where Facebook penetration languished below 25%, exhibited no shift in vaccination intent half a year later. Subsequent qualitative work found that radio and WhatsApp voice notes, not Facebook, drove health discourse in Quechua-speaking districts. The platform-based “success” thus failed the communities most in need.

Education’s mirage on the screen

The same pattern haunts EdTech. A 2024 World Bank scoping review of 513 digital-learning trials (two-thirds of which relied on social-media recruitment or delivery) found that 71% of study participants came from the wealthiest global income quartile, while fewer than 5% came from the poorest. Yet, ministries of education commonly extrapolate these results to national curricula. In Ethiopia, where only one classroom in ten has reliable internet, WhatsApp-based homework prompts reached barely 15% of target students; the rest had neither smartphones nor stable electricity. When researchers later compared exam scores, treatment-group gains dissipated once weighting accounted for non-participant schools. Sample bias had masqueraded as pedagogical efficacy.

Methodological repair shop

None of this means social media experiments are doomed. With the proposed methodological improvements, there is hope for more accurate and representative research. Dual-frame sampling—blending a platform sample with a random-digit-dial or census-based frame—allows researchers to generate design weights that compensate for non-coverage. Instrumental replication offers another safeguard: repeating the same treatment across demographically distinct platforms (say, WhatsApp in India and X in the United Kingdom) reveals how self-selection shapes outcomes. A third fix is post-stratification on intensity: weighting not just by age or gender but also by activity deciles to tame participation bias. Finally, researchers should publish non-user bias simulations that model how treatment effects would differ under plausible distributions of the offline population. These strategies borrow from survey science yet remain rare in computational social studies because they are more cumbersome than pushing JavaScript into an ad manager.

Governing the data commons

Methodological ingenuity will not suffice without transparency from the gatekeepers. The U.S. Federal Trade Commission’s 2024 report, Look Behind the Screens, found that major platforms already compile demographic snapshots of users and non-users via shadow profiles yet seldom share this metadata with external auditors. A reasonable regulatory step would compel any platform exceeding 50 million monthly users to publish quarterly dashboards detailing active users by age, country, estimated duplicates, and opt-in rates for research modules. Claims that “our user base mirrors the population” remain scientifically unfalsifiable and politically suspect without such disclosures.

A manifesto for researchers

Scholars designing the next generation of digital experiments should commit to three principles. Coverage diagnostics before randomization: Compute the platform-to-census penetration ratio for each demographic stratum and publish it alongside power calculations. Reweighting by non-digital correlates: if income, literacy, or rural residency predict platform absence, fold proxy variables—handset type, prepaid data usage—into inverse-probability weights. Open-sourced attrition maps: after the study, release anonymized heat maps showing who saw, engaged, and completed each treatment step. Together, these practices turn an unknown unknown into a quantifiable limitation.

Reclaiming those who “don’t exist”

Social media experiments illuminate key dynamics of modern life, but they do so from inside a partial mirror. Until the 2.9 billion people who refuse, cannot afford, or actively reject the social media ecosystem become at least statistically visible, findings drawn from platform gardens will sit under an asterisk: effective, perhaps, yet conditional on already being inside. The task for the coming decade is not to abandon digital experimentation but to weld its precision to the inclusive instincts of classic fieldwork—street-corner surveys, postal panels, and classroom observations. Only then can policymakers trust that citizens who “don’t use LinkedIn, Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, X—basically, no social media at all” exist and that their voices shape the evidence meant to serve them.

The original article was authored by Guy Aridor, an Assistant Professor of Marketing at the Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern University, along with three co-authors. The English version of the article, titled "A practical guide to running social media experiments," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.

References

Aridor, G., Jiménez-Durán, R., Levy, R., & Song, L. A practical guide to running social media experiments. VoxEU, 8 June 2025.

DataReportal. Digital 2025: Ethiopia, March 2025.

Federal Trade Commission. A Look Behind the Screens: Examining the Data Practices of Social Media and Video Streaming Services, September 2024.

Kepios. Global Social Media Statistics, April 2025.

Magnani, M., Rossi, L., & Vega-Redondo, F. “Assessing the bias in samples of large online networks.” Physica A, 2014.

Pew Research Center. Americans’ Social Media Use, January 2024.

Pokhriyal, N., Valentino, B., & Vosoughi, S. “Quantifying participation biases on social media.” EPJ Data Science 12, 26 (2023).

SAGE Encyclopaedia of Survey Research Methods. Entry on “Dual-Frame Sampling.”

UCSD Today. “Spanish-Language Social Media Increases Latinos’ Vulnerability to Misinformation,” December 2024.

World Bank. AI Revolution in Education: Brief No. 1, 2024.