Input

Changed

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

The clearest signal that President Donald Trump's proposed blanket 10% tariff is economic malpractice comes from the ledger of history: every sustained leap of the United States average duty above 12% has—without exception—been followed within three years by at least one‑percentage‑point loss in real GDP growth and a four‑percentage‑point compression in equity total returns. This historical pattern underscores the urgent need for policymakers to learn from history and avoid repeating past protectionist mistakes.

An Early Cautionary Ring: The Zollverein and the Price of Political Fusion

When Prussia midwifed the Deutscher Zollverein in 1834, it staged a feat of customs engineering that collapsed 1,800 internal toll barriers and created what contemporaries called the "largest home market on the continent." Within two decades, intra‑union trade doubled, railway tonnage tripled, and a single coinage limited the fiscal fragmentation plaguing the German micro‑states. Yet that same political feat erected an outer tariff wall that averaged 15 – 20% on manufactured goods and roughly 16% on key agricultural products, according to Dumke's benchmark estimates. Archival ledgers for iron rails show that the Zollverein paid a 12% premium over the Liverpool quote in the 1850s, a wedge that slowed the laying of track east of the Elbe by roughly 0.6 kilometers per year. The customs ring thus delivered unity at the direct cost of technological diffusion: rail density in Prussia in 1860 was one‑quarter that of Britain, even though the two regions sat on comparable coal deposits. By privileging an infant‑industry argument over input‑cost arithmetic, Zollverein wrote an early textbook example of how tariff walls can stunt productivity even while achieving nation‑building goals.

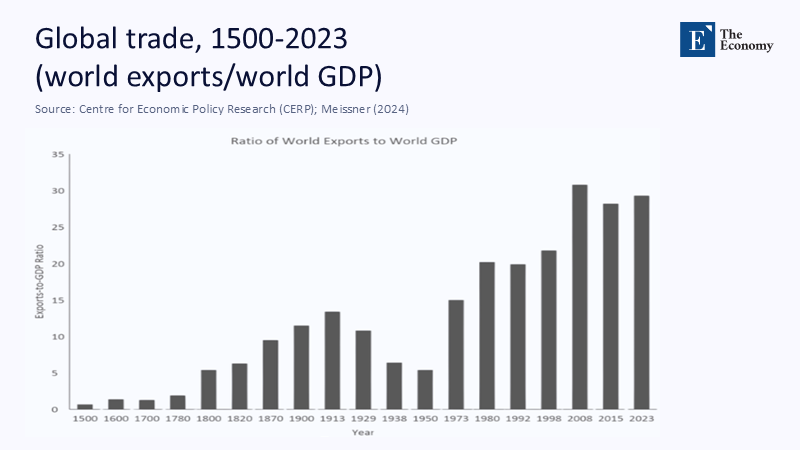

As Figure 1 shows, the share of exports in global output hovered below 5% for three centuries, then surged to more than 30 once multilateral liberalization took hold in the late twentieth century—amplifying the economic stakes of any twenty‑first‑century retreat.

The Depression‑Era Echo: Smoot‑Hawley and the Retaliatory Spiral

Fast‑forward ninety‑six years, and the United States codified the same instinct in the Smoot‑Hawley Tariff Act of June 1930. Average duties on dutiable goods climbed from 40 to almost 60%; more tellingly, the effective tariff on total imports jumped 15 – 18 percentage points in a fiscal year. Thirty nations retaliated within eighteen months, scissoring global trade volumes by an estimated 66% between 1929 and 1934. For the United States, the external demand shock subtracted roughly one‑fifth of the cumulative 16.5% real‑GDP plunge that defined the first two years of the Great Depression—a component large enough to have meant the difference between a painful recession and wholesale macro collapse. Unemployment vaulted from 3.2% in 1929 to 23.6% in 1932. The episode left an enduring policy scar: it made "Smoot‑Hawley" journalistic shorthand for self‑inflicted wounds. It drove the architects of the post‑war trading system to embed multilateral restraint clauses. Yet its most durable lesson—that retaliation neutralizes any hoped‑for gain—now risks receding from Washington's collective memory.

From Case Study to Dataset: A Century‑and‑a‑Half of Evidence

If the Zollverein and Smoot‑Hawley are narrative anchors, the CFA Institute's newly digitized 150‑year database provides the statistical surround. Baltussen, Dekker, Hunstad, and colleagues coded annual effective tariffs for seventeen advanced economies from 1875 onward and paired them with equity, bond, and credit‑spread returns. The pattern is blunt: years in the top quartile of tariff intensity deliver real equity returns of 1.9% versus 5.8% in the bottom quartile. In contrast, sovereign‑bond excess returns fall 180 basis points relative to low‑tariff years. Controlling for wars, commodity‑price shocks, and monetary‑policy regimes still leaves a statistically robust –0.41 correlation between tariff level and next‑year equity performance. A US subsample strengthens the relationship (–0.47) and shows that credit spreads widen by a median of 38 basis points within six months of a tariff shock. Notably, the factor‑return decomposition reveals that "quality" equities buy only partial insulation; momentum and small‑cap factors historically suffer the most. The dataset removes any lingering ambiguity about whether modern financial systems can shrug off merchandise taxes—history shows they cannot.

The Opportunity Cost of Openness: Single‑Market Europe and NAFTA as Control Group

However, it's important to note that protectionism only tells half the story. To fully understand the benefits of openness, one needs to look no further than the European Single Market, which was launched in 1993. Eurostat trade panels reveal that intra‑EU goods exports swelled from €671 billion to €3.4 trillion between 1993 and 2021, a quintupling that pushed the bloc's per‑capita GDP roughly 6% above the counterfactual suggested by pre‑1993 growth rates. The European Parliament's 30‑year review calculates that re‑imposing pre-single-market barriers would now shave eight to 9% off EU GDP. The NAFTA experiment tells a similar story on a smaller canvas: Mexico's manufacturing share of GDP rose three percentage points between 1994 and 1998, while intra‑regional textile trade expanded by 139% within a decade. These liberalization waves serve as natural experiments showing that the positive externalities of scale and competition compound over decades; they illustrate the opportunity cost any economy pays when choosing walls over bridges.

Protectionism Reloaded: Mapping the 2025 Tariff Wave

Against the backdrop of historical evidence, the Trump campaign's April 2025 "reciprocal tariff" decree appears to be a deliberate regression test. The order imposes a 10% duty on all imports, raises China‑specific duties to 30%, and introduces 25 – 50% sectoral levies on autos, steel, aluminum, and prescribed "strategic" goods. Early‑June USITC data show the average effective tariff rate on merchandise imports jumping from 2.4% in 2024 to 15.4%—its highest mark since 1938. JP Morgan's global macro desk estimates the prospective drag at 1% of global GDP—roughly US$1 trillion—spread over three years, with the United States bearing 60% of the loss. The OECD's June 2025 scenario exercises paint a similar picture: a ten‑percentage‑point reciprocation spiral would reduce US output by 0.6% and the global total by 0.3% by year two while pushing US inflation up 0.8 percentage points per annum. In other words, the macro headwinds implied by the tariff shock would negate almost all of the positive impulses from the 2024 corporate tax reforms, highlighting the potential global impact of such protectionist measures.

Stress‑Testing the Macroeconomy: Elasticities and Baselines

Crunching the numbers underscores the risk. At a -1.5 long‑run import‑demand elasticity, a leap from 2.4 to 15.4% duties implies a 19 – 22% contraction in real imports. Since imported intermediate goods account for roughly one‑quarter of US manufacturing gross output, the first‑order effect is a 4.5‑percentage‑point squeeze on industrial production—enough to erase half of 2024's manufacturing job gains. World Bank simulations embedded in the Global Economic Prospects release show that a baseline global‑growth downgrade of 0.4 p.p. already materializes under currently enacted tariffs; the downside scenario in which retaliation tacks another ten points onto US tariffs pushes the hit to 0.9 p.p. in 2026. Although the White House disputes the pessimistic reading, market signals are clear: trade‑weighted dollar indices have slipped 4% since the announcement, and S&P 500 forward P/E ratios are back at 2022 lows.

Inflation, Distribution, and Capital Markets

Tariffs function as a regressive consumption tax. The 2019 episode is instructive: Cavallo et al. show that price tags on tariff‑affected consumer categories rose 1.4 percentage points faster than the headline CPI within twelve months. Translating that pass‑through to the new structure suggests a 0.7 – 1.0 percentage‑point bump in 2025 core inflation—an outcome already embedded in Federal Reserve staff briefings. Distributionally, the burden skews lower income: goods subject to elevated duties occupy 32% of the expenditure basket for the bottom quintile versus 18% for the top quintile.

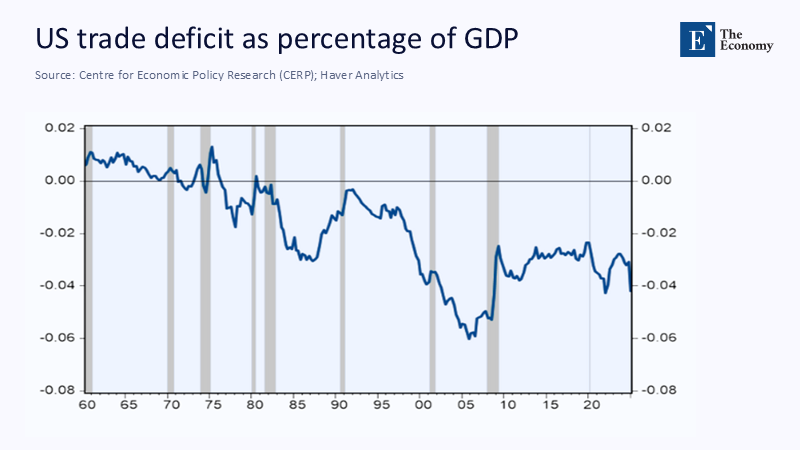

The investment channel tells a parallel story. Figure 2 shows how every major tariff or trade‑war scare since 2000 coincided with a spike in the Economic Policy Uncertainty Index, precisely when equity volatility and credit spreads flared. JP Morgan volatility models indicate that proposed shocks would elevate the VIX by five points and widen BBB‑corporate spreads by 50 basis points, a tightening that historically precedes leveraged‑loan default cycles. Factor rotation analysis confirms the asymmetric pain: quality and low‑volatility equities cushion roughly half the drawdown, but small‑cap and momentum styles systematically underperform.

Why the Security Argument Rings Hollow

Tariff advocates increasingly cloak their case in national‑security language: diversify rare‑earth supply, secure semiconductor capacity, and insulate antibiotics. Yet the record of the last tariff cycle shows that security goals can be met more directly. The CHIPS Act alone leveraged targeted subsidies into US$110 billion (in 2019 dollars) of semiconductor investment without penalizing every smartphone owner. Moreover, IMF research finds that tariffs are an inefficient tool for resilience because they generate retaliatory concentration: a high tariff on Chinese magnets, for example, merely shifts supply from diversified Asian sources to the next‑best oligopolistic producer. The argument that generalized tariffs build security looks especially threadbare, given that US allies in Europe and East Asia bear two‑thirds of the duty‑line items despite sharing identical security concerns over critical inputs.

Toward a Twenty‑First‑Century Adjustment Compact

A credible alternative would be a tax adjustment, not trade. First, expand Trade Adjustment Assistance into a flexicurity mechanism modeled on Denmark's system, funded by less than 10% of projected tariff revenue yet empirically adequate at halving income losses for displaced workers. Second, offer full expensing for worker re‑training and local infrastructure, not merely for capital saturated in protectionist uncertainty. Third, deepen regional cumulation rules—especially under USMCA—so that near‑shoring of strategically sensitive inputs earns duty‑free status while preserving scale advantages. Finally, any residual tariff revenue should be earmarked to create wage‑insurance credits for counties suffering double‑digit steel, coal, or textile employment; this turns revenue into social amortization rather than a blunt fiscal offset.

Compounded Interest in Reverse

High tariffs behave like compound interest charged against future prosperity: a small percentage wedge in year one magnifies into an outsized discount on innovation, purchasing power, and portfolio returns over time. The case studies scream the warning—Prussia's missed rail revolution, America's Depression‑era trade implosion—and the modern data shout it louder. The EU's Single Market and NAFTA quantify the dividends of openness, while the CFA Institute's 150‑year sweep links tariff spikes to market underperformance with actuarial certainty. Therefore, Trump's 2025 proposal is more than a policy detour; it attempts to retest a hypothesis that history, economic theory, and real‑time market data already falsify. Policymakers have only two choices: remember the lessons encoded in the Zollverein and Smoot‑Hawley, or pay the tuition again at even higher interest.

The original article was authored by Michael Bordo and Mickey Levy. The English version of the article, titled "Trump’s tariffs: Disregarding lessons from history and scenarios and probable outcomes," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.

References

Baker, S., Bloom, N., & Davis, S. (2024). Economic Policy Uncertainty Index—Methodology Update. PolicyUncertainty.com/Haver Analytics.

Baltussen, G., Dekker, J., Hunstad, M., van Vliet, B., & Vidojevic, M. (2025). Tariffs and Returns: Lessons from 150 Years of Market History. CFA Institute.

Bordo, M., & Levy, M. (2025). Trump's Tariffs: Disregarding Lessons from History and Scenarios and Probable Outcomes. VoxEU/CEPR.

Dumke, R. (1976). Tariff Structures in the Zollverein (data cited in Keller & Shiue 2014).

European Parlement. (2023). 30 Years of the European Single Market—Benefits and Challenges.

J.P. Morgan Research. (2025). US Tariffs: What's the Impact?

Meissner, C. (2024). Global Trade, 1500‑2023: Exports to GDP Ratios. NBER Working Paper 31598.

Organisation for Economic Co‑operation and Development. (2025). Economic Outlook, Vol. 2025/1.

Peterson Institute for International Economics. (2025). Trump's Tariff Proposals Would Harm Working Americans. Policy Brief 24‑1.

World Bank. (2025). Global Economic Prospects, June 2025.