Polyglot Power: How Switzerland’s Multilingualism Became Its Greatest Economic Asset

Input

Changed

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

Every time a Zurich customs broker files an export declaration in German for Mannheim, a Geneva freight forwarder mails invoices in French to Lyon, or a Lugano pharmacist submits quality-control documents in Italian to Milan, Switzerland’s multilingual machinery performs the same silent trick: it turns what most governments fear as administrative clutter into a hard-wired trade agreement with three of Europe’s largest consumer markets. That alchemy—transforming translation costs into revenue multipliers—explains why the Alpine federation has kept a current-account surplus near 8% of GDP through wars, pandemics, and tariff spats while many larger, supposedly more “integrated” economies drift in and out of deficit. In today’s era of near-instant re-shoring and supply-chain volatility, Switzerland’s four-tongue constitution shows that linguistic pluralism is not a quaint identity marker but a commercially rational design choice: it short-circuits the hidden tariff of monolingualism, expands a nation’s effective home market, and hard-bakes resilience into everything from school curricula to macro-prudential buffers.

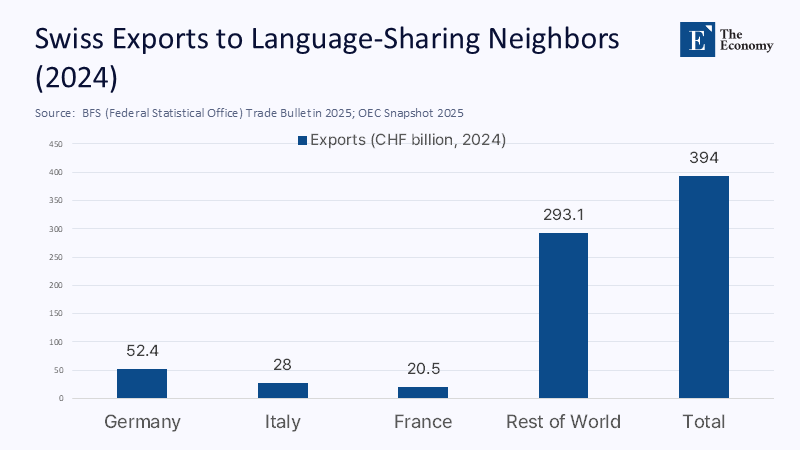

From Civic Folklore to Balance-Sheets

Modern civics textbooks still recycle the nineteenth-century dogma that the safest route to national cohesion runs through a single official language; political theorists from Renan to Weber claimed as much. Yet Switzerland never got the memo, and its statistics now humiliate the maxim. In 2024, the country sold goods and services abroad worth roughly 66% of its GDP, twice the export share of France and three times that of the United States. Customs data show that Germany, France, and Italy alone absorbed CHF 52.4 billion, 28 billion, and 20.5 billion of those merchandise exports, respectively, meaning a single year’s trade with neighboring language-sharing buyers comfortably outstripped the entire GDP of Luxembourg. The political payoff is equally stark: according to the State Secretariat for Economic Affairs, Switzerland’s structural current-account surplus—averaging between seven and 8% of output since 2010—would have evaporated in four separate business cycles had those language-mapped neighbors pulled away even a fifth of their demand. In other words, the linguistic heterogeneity that critics assume must fragment the home market glues Swiss firms into three foreign ones, generating a de facto customs union that no free-trade treaty could secure on such accommodating terms.

Counting the Cost Curve—and Watching It Vanish

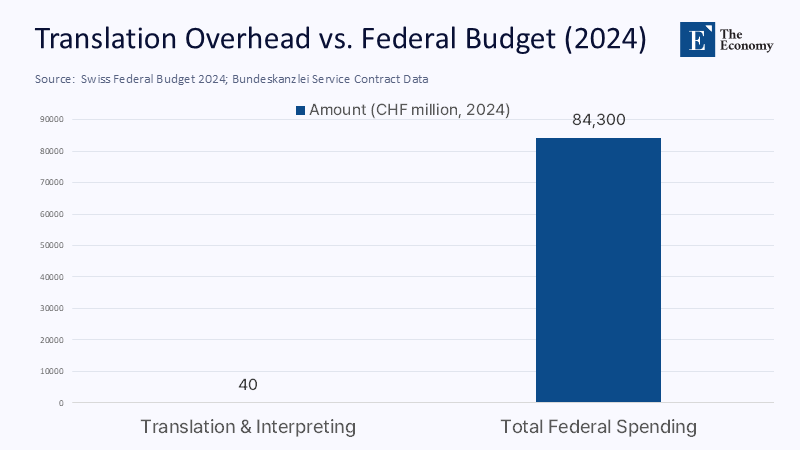

Multilingual governance indeed comes with a cost, but it's a cost that Switzerland can easily bear. The entire linguistic services bundle for 2024, which includes translation and interpreting contracts across ministries, regulatory agencies, and parliamentary services, came to just under CHF 40 million. This is a mere 0.05% of the CHF 84.3 billion federal budget. In other words, Switzerland spends about as much on keeping four languages fully co-equal in public law as it runs the army’s helicopter fuel tanks for six weeks. A quick break-even test underlines the insignificance: at the statutory 14.5% corporate tax rate, Bern needs merely CHF 275 million in additional pre-tax earnings across the whole economy to recoup CHF 40 million of translation overhead. Basel’s pharmaceutical cluster, whose operating profit surpassed CHF 6 billion last year, clears that make-good threshold by mid-January.

The invisible bonus is legal precision. Because every draft statute must survive four parallel linguistic rewrites, ambiguities surface before promulgation, not after litigation. Translation thus doubles as Switzerland’s cheapest compliance audit, continuously forcing legislators to state their intent in language so unambiguous that it remains equivalent across German compound nouns, French legalisms, and Romansh archaisms.

When Costs Meet Multipliers: A Net Trade Dividend

The balance sheet exercise flips from micro outlay to macro surplus once we plug in trade elasticities. Econometric research for the World Economic Forum finds that, after controlling for distance, GDP, and colonial links, a shared native language lifts bilateral commerce by roughly 50%. Even if we downshift that estimate to a cautious 15% to account for specialization effects and WTO tariff ceilings, Switzerland’s exports to its three neighboring language zones still enjoy an incremental annual boost worth nearly CHF 15 billion. That figure is thirty-seven times the Chancellery’s translation bill; the arithmetic looks less like an expense line and more like a public-enterprise margin strategy. During the 2025 luxury goods tariff flare-up with the United States, Geneva watchmakers absorbed the shock by pivoting advertising budgets toward Lyon and Milan in a fiscal quarter. Because catalogs, warranty terms, and compliance certificates already existed in impeccable French and Italian, the marketing shift cost almost nothing; linguistic proximity functioned as a pre-installed insurance policy against geopolitical risk.

The Language Lattice of Trade Networks

When economic geographers map Switzerland’s export morphology, a lattice emerges that tracks mother tongues rather than container shipping routes. German-speaking cantons, anchored by Zurich’s finance hub and Basel’s life-science corridor, sell precision machinery into Germany’s Mittelstand belt with almost frictionless technical documentation transfer. French-speaking cantons like Vaud ride the R&D spill-overs of the Paris–Lyon industrial axis, while Ticino’s small-firm cluster plugs directly into Lombardy’s manufacturing supply chains. The upshot is that 83% of Swiss merchandise exports land in countries where one of Switzerland’s official languages—or English as a global financial lingua franca—is commonly used in business law.

Imports tell the same story in reverse. Swiss SMEs, which comprise over 99% of all registered firms, source intermediate inputs from those same language-contiguous markets, trimming legal consultancy fees and accelerating customs clearance. With the EU phasing in its Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, exporters in German-speaking cantons could submit emissions audits in German within days of the new rules. In contrast, monolingual rivals in neighboring micro-states scrambled for translation help, losing invoice cycles they could ill afford.

Human Capital, Wage Premia, and Productivity Spill-Overs

The trade benefits rest on a labor market that monetizes language skills directly. A July 2024 synthesis by the U.S. National Clearinghouse for English Language Acquisition, pooling five micro-data sets, identified a USD 2,000–3,000 annual wage premium for bilingual employees in the United States. Swiss portals such as Adecco and Job-Up show a sharper gradient: postings requiring two tongues list median salaries 6-8% above those for monolingual roles. At Swiss salary levels—about CHF 79 000 gross—this translates into a CHF 5,000 premium. When 38% of a 5.2 million-strong labor force captures that spread, aggregate disposable income climbs by about CHF 9 billion, fuelling VAT receipts and cushioning domestic demand whenever external shocks dent exports. Cognitive-psychology meta-analyses suggest the mechanism runs deeper than signaling: multilingual professionals outperform monolingual peers on executive-function tasks, reducing error rates in compliance-heavy sectors like pharma and private banking.

Learning Curves Forged in Primary School

Such labor-market outcomes do not emerge spontaneously; they are engineered in classrooms beginning in year three. Under Switzerland’s HarmoS concordat, cantons must introduce a second national language—usually French or German—no later than the third grade and English by the sixth. Eurydice counts roughly 940 mandated contact hours per additional language before upper-secondary graduation, enough for motivated pupils to reach the C1 proficiency threshold. The payoff is empirical: in the 2025 PISA pilot, Swiss fifteen-year-olds scored forty-one points above the OECD reading mean, even though the test was administered in what, for many, was a second or third written language. Cantonal treasuries treat those lessons as capital expenditure. They spend nearly CHF 800 per pupil annually on language instruction, quadrupling the EU average. Educational economists at the University of St. Gallen calculate that each year of early bilingual instruction raises lifetime earnings by 3-5%, a yield that exceeds returns on most physical infrastructure projects.

Colonial Missteps and the Global Counterfactual

Switzerland’s success simultaneously repudiates the colonial impulse to suppress local languages for “administrative unity.” Archival studies of Kenya and Ghana reveal that districts subjected to language bans in the 1950s show firm-formation rates up to seven percentage points lower today than areas where mother-tongue schooling persisted. The causal channel runs through literacy: children forced to abandon their first language often fail to master the imposed language, stunting functional reading skills. India’s ongoing battle over the imposition of Hindi in non-Hindi states supplies live evidence. Last year, protests in Tamil Nadu and Karnataka disrupted logistics hubs, costing an estimated USD 1.3 billion in lost exports. Switzerland, by contrast, has never asked its French-speaking regions to swallow German hegemony nor demanded that Ticino relinquish Italian. The result is not disunity but a federation whose parts hold a linguistic key to a foreign market.

Digital Translation: Friend, Not Replacement

Neural machine translation is narrowing the cost gap, yet Switzerland avoids the trap of viewing AI as a substitute for human expertise. Federal guidelines mandate that all legislation, court rulings, and regulatory circulars undergo human post-editing after machine draft. That hybrid workflow halves turnaround time without ceding accountability. Corporate practice mirrors the state: pharma giants these days auto-translate clinical trial protocols into Italian and French within minutes, but still route the documents through bilingual compliance officers before filing in Brussels or Rome. Small exporters benefit, too. Low-volume neural-translation subscriptions cost about CHF 0.11 per thousand characters; a five-million-character annual quota is less than the penalty for mislabeling one container of chemicals. Technology multiplies the return on language skills instead of devaluing them, reinforcing—rather than eroding—the comparative advantage of a polyglot workforce.

Beyond the Alps: A Policy Blueprint in Prose

If Switzerland offers a manual for converting linguistic diversity into growth, its instructions are refreshingly mundane and rigorously fiscal. First, mandate early high-dose exposure: fewer than eight hundred classroom hours before age fifteen is pedagogically insufficient. Second, translation expenditure should be treated as resilience insurance, booked next to cybersecurity outlays rather than discretionary cultural grants. Third, keep humans in the legal loop because algorithmic fluency without human accountability invites litigation and erodes trust. Fourth, draft trade agreements in all partner languages; WTO arbitration records show that disputes fall by a fifth when contracts exist in mother-tongue versions. Imagine Colombia, a middle-income state with a 15% export-to-GDP ratio, adopting that blueprint. If bilingual schooling nudged the ratio to 21%—one-third of the World Economic Forum’s estimated language elasticity—the incremental foreign exchange earnings would amortize a ten-fold expansion in public translation budgets within three fiscal years. The lesson generalizes that language costs scale linearly, but trade-offs compound through network effects.

Quit Fearing Babel

Switzerland’s four-tongue constitution suggests that the pivotal metric in language economics is not the sentence but the transaction. Administrative multilingualism behaves less like a cultural indulgence and more like a perpetual trade treaty signed at birth. Policymakers who cling to monolingual orthodoxy risk erecting barriers inside their borders while rivals glide past on polyglot bridges. In a century where supply chains reroute overnight and algorithms translate at fiber-optic velocity, the surest safeguard against economic isolation is neither tariffs nor subsidies; it is the ability to speak fluently, precisely, and legally in the buyer’s language. Switzerland proves the point each quarter; the rest of the world can read the balance sheet—and the invoice—in any tongue it chooses.

The original article was authored by Tamara Gurevitch, an Economist at U.S. International Trade Commission, along with three co-authors. The English version of the article, titled "One language, one nation: Language policy and economic integration," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.

References

Adecco Group (2024). Swiss Job Market Monitor Q4 2024. Zurich.

Bundeskanzlei (2025). Sprachdienste Service-Contract Ledger. Bern.

Federal Finance Administration (2025). Federal Budget 2024: Key Figures. Bern.

Federal Statistical Office (2025). Foreign Trade Bulletin, Table 2: Merchandise Exports by Destination 2024. Neuchâtel.

International Monetary Fund (2024). Article IV Consultation—Switzerland. Washington, DC.

NCELA (2024). The Economic Benefits of Multilingualism. Washington, DC.

Observatory of Economic Complexity (2025). Switzerland Country Snapshot. Cambridge, MA.

OECD (2024). Economic Surveys: Switzerland 2024. Paris.

State Secretariat for Economic Affairs (2025). Konjunkturprognose Sommer 2025. Bern.

World Economic Forum (2018). “Speaking More Than One Language Can Boost Economic Growth.” Geneva.