The Unfinished Classroom—Why Europe Still Conducts Its Greatest Brain-Drain Experiment on Itself

Input

Modified

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

On a late spring morning this year, Italy's national statistics bureau quietly released one more grim ledger: the eight regions south of Rome—home to over a third of Italians—produced just €380 billion in output, representing barely 22% of the country's national GDP. Two clicks away, Eurostat's mobility dashboard painted a matching continental vignette: since 2020, 1.3 million under-thirty-fives from Spain, Portugal, Italy, and Greece have registered for social insurance north of the Alps, and graduates from those four countries now supply one in ten high-skill hires in Germany. Add the OECD's discovery that every graduate who leaves the Mezzogiorno represents a public investment of roughly €240,000, and a century-old equation resurfaces with digital clarity: human capital flows follow opportunity, fiscal returns follow human capital, and the South is left subsidizing prosperity that accrues in the North. Unified Italy learned that lesson the hard way after 1861; the euro area has been rehearsing it ever since the single currency's first notes hit wallets in 2002. The urgency of this issue cannot be overstated as the economic disparities continue to widen.

Reframing the Historic Divide: From Garibaldi to the Eurotower

Italian unification, as the reference article details, entrenched rather than eased the gulf between Milan's factory floor and Sicily's citrus groves. That historical pattern foreshadowed the trajectory of the entire Mediterranean arc in the Euro era, where structural asymmetries have replicated the same northward concentration of labor and capital. Where Piedmont once drew labor and capital northward under a new tricolor, the euro's structural asymmetries—common money, divergent competitiveness—have channeled today's talent toward Frankfurt, Amsterdam, and Copenhagen. The timing matters: Europe is midway through deploying the €723 billion NextGenerationEU fund, a crisis instrument explicitly tied to skills and digital modernization. If policy-makers ignore Italy's cautionary tale—investment without embedded retention strategies creates centrifugal forces—the recovery plan may deepen, not bridge, the continental divide. In educational terms, Europe risks writing a second chapter in the same textbook: the South pays tuition, while the North reaps the benefits of the diploma.

The Dataframe of Divergence: 2025 in Cold Numbers

New evidence suggests that the rate of divergence is accelerating. ISTAT's June 2025 regional tables set per-capita GDP in Lombardy at €36,100 and in Calabria at €19,500, reproducing—after inflation adjustment—the same 58-percent ratio recorded in 2000. Cross-check the wider euro area: Eurostat pegs hourly labor costs at €39.90 in Germany and €13.60 in Greece. At the same time, the European Commission's new Regional Competitiveness Index assigns the Mezzogiorno an average score of 80, compared to the northern Italian figure of 121 (with the EU-27 baseline set at 100). Migration flows reflect the gap: Germany's Federal Migration Report records 97,000 new EU Blue Cards in 2024; of holders educated in Europe, 28% arrived from the four southern members that spend proportionally the most on public higher education relative to their GDP. Where granular micro-data are patchy, estimates fill in the gaps. Eurostat recorded 1.5 million intra-EU moves in 2023. Overlaying origin-destination matrices and the south-to-north share reveals an approach of about 27%, equating to a depletion of approximately 0.6% of the southern working-age cohort each year.

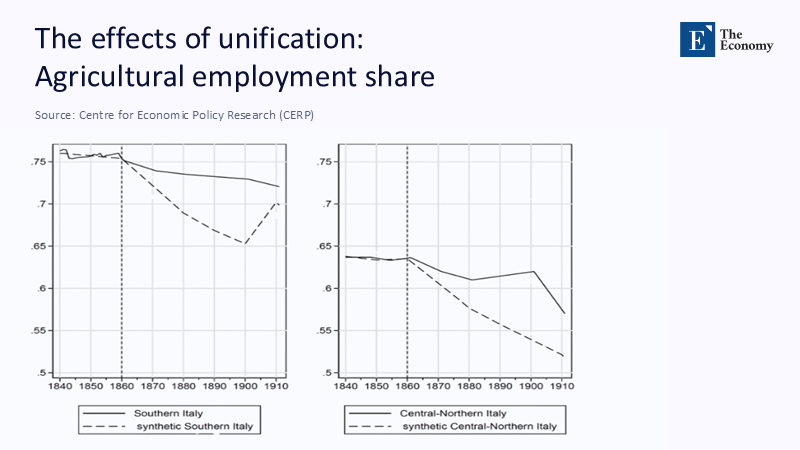

Historical labour trends help illuminate the origins of today’s economic divergence. In the wake of Italy’s unification, agricultural employment remained persistently high in the south, contrary to what synthetic regional models predicted under equal development conditions. While the North diversified into manufacturing, the South’s structural transition stalled, laying the groundwork for today’s uneven productivity map.

Mobility's Hidden Costs: When Opportunity Becomes Extraction

Mobility, economists remind us, is a release valve in a monetary union lacking fiscal transfers. Yet its equilibrium flips when origin regions finance public goods—the schooling, the health checks, the broadband backbone—whose dividends materialize elsewhere. Italian Treasury economists estimate that each graduate who migrates north shifts an average lifetime net-present-value tax flow of €240,000 out of the Mezzogiorno. Scale that across the 147,000 southern Italians aged 22-34 currently registered in northern metropolitan areas, and the implicit fiscal transfer exceeds €35 billion, almost identical to Italy's entire annual state school budget. The social consequences are more complex to monetize but equally corrosive. Enrolment in Sardinian primary schools has dropped by 14% since 2015, forcing the use of multi-grade classrooms and accelerating a vicious circle: fewer pupils justify fewer teachers, which undermines educational quality and, in turn, nudges the next cohort's parents toward emigration before their children even graduate.

Education as the Quiet Multiplier of Imbalance

Education exerts leverage at three layers: entry pipelines, curricular alignment, and research ecosystems. While upper-secondary completion gaps have narrowed—Italy slashed its dropout rate from 24% in 2010 to 20% in 2023—post-secondary outcomes diverge sharply in content. Universities south of Rome still lean toward humanities and low-capital life sciences, whereas demand spikes in AI engineering, cloud architecture, and biotech clusters around Milan, Munich, and Rotterdam. Part of the mismatch is structural: the Mezzogiorno secures only 16% of Italy's 2024 R&D budget despite educating 34% of the population. At the European scale, Horizon Europe grants tilt even more strongly northward; the Netherlands alone captured more than the entire Iberian peninsula in the 2021–24 tranche. In effect, the South's campus network functions as an export industry subsidizing advanced supply chains elsewhere. Without place-conscious R&D funds, the cycle self-reinforces: graduates depart, local laboratories thin out, intellectual property migrates with them, and regional firms lack the knowledge spillovers necessary to absorb future graduates.

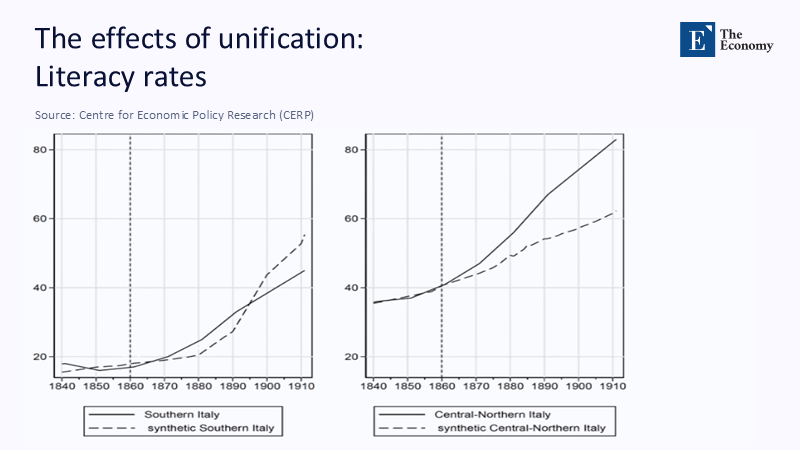

The North–South educational gap is not a new phenomenon. Data from the post-unification period reveal a striking divergence: even as national literacy rates climbed steadily, Southern Italy remained behind both its projected progress and the actual progress in the north. This underscores how geography has shaped the ability to absorb policy reforms, with southern institutions facing deeper structural obstacles that persist to the present day.

Digital Work: New Hope or Same Old Geography?

Remote work initially looked like the South's wildcard. In 2021, a McKinsey survey found that 21% of Italian digital workers were operating for firms headquartered abroad. Yet payroll data unmask an uncomfortable twist: only 7% of those remote-work contracts list a southern regional tax domicile after two years, suggesting eventual physical relocation to metropolitan hubs, with or without the laptop. The digital divide persists both online and offline. The average household broadband speed in Lombardy stands at 99 Mbps, compared to 48 Mbps in Basilicata, which hinders the effective adoption of telework and digital services. Smart-village pilots in Abruzzo show promise: subsidized fiber, local co-working hubs, and startup tax holidays have increased graduate retention by eight percentage points over five years, proving that virtual connectivity still requires very concrete poles and wires—and policy scaffolding—to bridge geography.

Policy Levers: Toward a Capability-Conscious Compact

Fixing the imbalance means shifting from place-blind transfers to capability-conscious compacts. Three levers merit immediate deployment. First, earmark at least 30% of the Recovery and Resilience Facility's education lines for lagging regions, with payouts contingent on five-year graduate retention rates—a policy analogous to outcome-based healthcare funding that rewards real-world impact. Second, create a Mobility Dividend: when a graduate educated in one member state pays taxes in another, the Treasury of the destination country would automatically rebate a pre-agreed slice—say, 15%—of their income tax to the education budget of the origin region. The EU already operates cross-border reimbursement for healthcare costs; extending that principle to human capital is an administrative, not conceptual, leap. Third, expand Erasmus+ into reverse fellowships that underwrite northern professors on sabbatical in southern universities, building bidirectional networks rather than one-way exits. Italy could go a step further with Regional Skills Bonds. Much like municipal green bonds, Mezzogiorno cities would securitize future local income tax receipts from graduates who stay, using the upfront capital to fund campus laboratories and seed accelerators and match private R&D grants.

Anticipating the Skeptics: Freedom, Efficiency, and Moral Hazard

Skeptics marshal three objections. First, any retention-linked subsidy is likely to distort market efficiency. But the single market is already distorted by historical capital concentration; acknowledging that fact and designing corrective feedback loops increases, not decreases, allocative efficiency over time. Second, compensating origin regions penalizes the freedom of workers. The Mobility Dividend targets public, not private, externalities: graduates remain free to move; states settle the invoice for publicly financed skills. Third, targeted regional funds breed dependency. Bank of Italy research on EU-funded procurement in 2021-23 tells a different story: when grants were coupled with stringent milestones, southern firms out-innovated their northern peers in terms of patent filings relative to their baseline capital stock; conditionality, not paternalism, unlocked performance. In short, the cure for dependency is not austerity but accountable investment.

Turning the Page on the Classroom Divide

Referring back to the statistics introduced in this article, approximately one-third of Italy's population contributes only about one-fifth of its overall production. At the same time, over a million southern Europeans currently support the tax revenues of the northern regions. The absence of feedback loops has turned the classroom into Europe's most consistent export industry, with tuition paid in Naples and dividends booked in Hamburg. If the euro area's recovery funds flow through the same channels that entrenched a century of imbalance, Europe will have financed its brain-drain experiment for another generation. Yet the blueprint for change is within reach: tie investment to retention, price human-capital flows like the shared currency they are, and build research ecosystems where talent is born rather than where it merely arrives. Europe has long graded itself on how freely its people can move; in the next chapter, it must also grade itself on how freely every region can prosper.

The original article was authored by Guglielmo Barone, a Professor of Economics at the University of Bologna. The English version of the article, titled "A cold case (over 160 years old): The effects of unification on Italy’s North-South divide," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.

References

Bank of Italy. Regional Developments and Outlook in the Mezzogiorno 2024. Rome, 2024.

European Central Bank. "Foreign Workers: A Lever for Economic Growth." ECB Blog, 8 May 2025.

European Commission. Annual Report on the Euro Area 2024. Brussels, 2024.

Eurostat. Migration and Asylum in Europe – 2024 Edition. Luxembourg, 2024.

Eurostat. Regions in Europe – 2024 Edition. Luxembourg, 2024.

Eurostat. "Regional Labour Market Statistics." Luxembourg, February 2025.

IEMed. "Southern European Migration Towards Northern Europe." Barcelona, 2023.

ISTAT. Regional Economic Accounts 1995–2023. Rome, June 2025.

McKinsey Global Institute. Remote Work in Europe: The Post-Pandemic Geography of Talent. New York, 2021.

OECD. Education at a Glance 2024: Italy Country Note. Paris, 2024.

Reuters. "Bank of Italy Sees Signs of Recovery in Chronically Weak South." 19 September 2024.

Reuters. "Germany Issues Record Number of EU Blue Cards in 2024." 2 January 2025.

VoxEU. "Cold Case Over 160 Years Old: The Effects of Unification on Italy's North–South Divide." London, 2023.