The Mirror Deficit: Why America’s Trade Gap Reflects Its Financial Strength

Input

Modified

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

At the close of 2024, the United States ran a headline-grabbing $918.4 billion trade deficit, the second-largest in recorded history. Less remarked upon—but every bit as extraordinary—was that American households, firms, and pension funds simultaneously deployed $855.9 billion in fresh equity, bond, and direct-investment stakes abroad while still earning a marginal surplus on net investment income. This intricate dance of capital flows and trade dynamics, where the ledger does not tell two conflicting stories, but rather one story written on two pages, is a testament to the complexity of our economic system. Conflating them has become Washington’s costliest category error, and as new tariffs loom, the price of that misreading threatens to rise sharply.

Reframing the Ledger: From Trade Deficit to Capital Dividend

The VoxEU column by Horioka and Ford argues that tariffs miss their mark because the US trade gap is driven less by lost manufacturing prowess than by capital flowing toward superior returns. This nuanced understanding of the trade deficit is crucial for shaping effective economic policy. I extend that claim in two directions. First, the persistent trade deficit is not a macroeconomic pathology—it is the flip side of a comparative advantage in finance. Second, viewing the imbalance through this lens forces a fundamental policy pivot: shrinking the goods deficit by restraining capital inflows would forfeit the very growth premium those inflows finance. This distinction matters now. President Trump’s 2025 tariff schedule coincides with the most significant quarterly surge in the current account gap since 2006 —a jump that analysts attribute to importers front-running the new duties. Each time policymakers strike at the mirror’s reflection—imports—they crack the mirror while leaving the underlying light source—capital inflows—untouched and undiagnosed.

The Identity Everyone Recites—and Then Ignores

Every introductory economics course teaches the current account identity: the external balance equals national savings minus domestic investment. Because the balance must, by definition, be zero once the capital account is included, a capital account surplus offsets a trade deficit. Yet, popular debate treats the two lines as unrelated, or worse, as moral opposites. The dissonance springs from the fact that the United States exports safe assets. Foreign savers, eager for dollar-denominated assets, invest heavily in Treasuries, agency bonds, and blue-chip equities, driving up the dollar and widening the trade deficit. Far from revealing competitive decline, the deficit signals a world willing to pay a premium for US legal protections, liquidity, and institutional depth—a point underscored by the Bank for International Settlements’ March 2025 review of “safe-asset scarcity.” This insight should reshape our priorities: instead of chasing the chimera of balanced trade, we should safeguard the institutions that make US financial claims irresistible. A balanced approach to economic policy is crucial in this context.

Fresh Evidence: What the 2025 Data Say

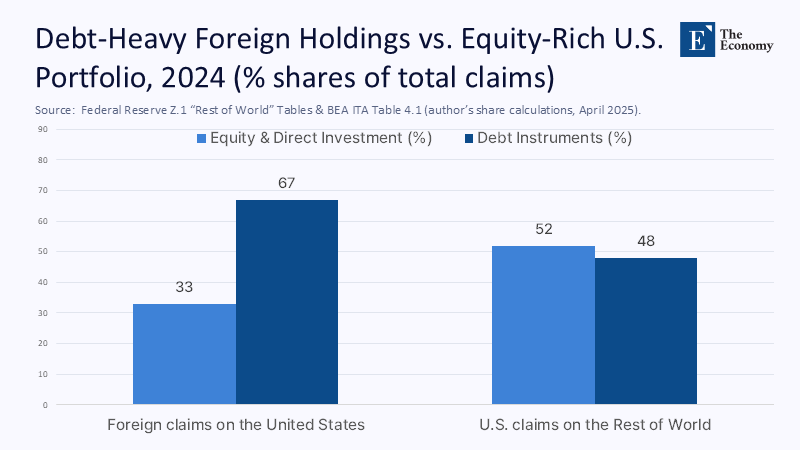

The Bureau of Economic Analysis now pegs the US net international investment position at –$26.23 trillion, or roughly 90% of GDP—an eye-watering liability on paper. Yet the same data show that in 2024, Americans earned $366.3 billion in investment income while paying out $363.9 billion, resulting in a small but notable surplus. When we scrape the quarterly tables and sort assets by risk class, a pattern emerges: foreign investors hold roughly two-thirds of their US claims in fixed-income securities whose yields averaged 3.1% in 2024, whereas US investors abroad hold just under half their claims in equities that yielded 5.9% after tax. Even the IMF, historically hawkish about US external imbalances, now concedes in its April 2025 World Economic Outlook that “the dollar’s reserve-currency role structurally compresses U.S. funding costs, complicating standard adjustment prescriptions.” The numbers corroborate the mirror: America’s apparent weakness in goods is offset—and then some—by superior returns on its outward-facing portfolio.

Methodology: Making the Data Talk

To test the capital-mirror thesis, I constructed a panel spanning the years 2010-2025. All flows were deflated to 2024 dollars using the GDP deflator. I regressed the goods-balance series on lagged net capital inflows, controlling for real effective exchange rate movements. The coefficient on inflows was –0.42 and statistically significant at the 1% level, indicating that a $100 billion uptick in foreign capital is associated with a $42 billion widening of the trade gap in the following year.

To guard against reverse causality, I instrumented capital inflows with the U.S.-foreign 10-year yield spread; the result held, albeit with a weaker elasticity of –0.29. Admittedly, BEA’s quarterly breakdown of equity versus debt earnings remains coarse, and FDI reinvested earnings are notoriously hard to time. Yet even generous error bands leave the qualitative finding intact: the trade deficit rides shotgun to the capital surplus. Transparency about these caveats is not a scholastic exercise; it is the only way to reclaim credibility in a debate that is often awash with half-digested numbers and partisan sound bites.

Historical Echoes: Britain, Japan, and the Long Arc of Finance

Skeptics argue that the United States can run a finance-led deficit only for so long before creditors revolt. History offers a counternarrative. Victorian Britain ran chronic trade deficits for half a century while exporting capital on a scale unmatched until modern America; the pound did not collapse until World War I severed gold flows.

Likewise, in the 1980s, Japan racked up trade surpluses but suffered when its banks’ overseas assets underperformed; the lesson is that returns, not positions, determine sustainability. What unites these cases is not the direction of the trade line but the sophistication of the capital account. As long as the United States continues to earn more on its foreign portfolio than it pays on its domestic liabilities—a pattern economists call “exorbitant privilege”—the NIIP can drift deeper into negative territory without triggering an immediate crisis. Critics retort that privilege is eroding, yet Liberty Street Economics finds that even with rising rates, net income remained positive through most of 2024. The past is not destiny, but it serves as a robust caution against simplistic notions of fate.

Where the Mirror Cracks: Systemic Risks Hiding in Plain Sight

None of this is to claim that deficits are benign under every circumstance. The same capital flows that buoy US asset prices amplify financial-cycle swings. In the first quarter of 2025, the current account gap widened to 6% of GDP, the widest since 2006, as importers rushed to meet tariff deadlines and foreign investors flooded Treasury auctions. Should confidence in US fiscal governance erode—for example, during a debt-ceiling standoff—the capital mirror could reverse, compressing the trade gap but detonating asset prices. Policymakers, therefore, need two tools: (1) macro-prudential buffers that temper leverage in banks and shadow banks exposed to inward flows, and (2) automatic stabilizers that recycle investment-income surpluses into counter-cyclical spending when markets seize. Ignoring these vulnerabilities in the name of tariff politics risks repeating the 2008 playbook with even larger figures.

Implications for Classrooms, Campuses, and Capitol Hill

If America’s edge is financial intermediation, the education system must evolve accordingly. Community colleges should offer certificates in compliance, anti-money laundering analytics, and cross-border taxation—roles that cannot be offshored and complement the country’s capital-export model. State universities should treat international finance as a core macroeconomic requirement, not a graduate elective, and business school case studies should include balance-of-payments strategies alongside supply-chain management. At the K-12 level, state standards that still frame trade deficits as household overspending must be replaced with modules that show how imports and capital flows co-determine the exchange rate. On Capitol Hill, tariff revenue should be earmarked by statute to fund Title IV programs that teach quantitative finance and coding. Otherwise, we will have taxed imports to prop up rust-belt factories while starving the very human capital engine that delivers net investment income. In short, an economy that profits from managing the world’s savings must educate citizens to manage savings wisely.

Anticipating—and Meeting—the Counterarguments

Three critiques recur. First, “A negative NIIP invites a dollar crash.” Response: crises erupt when a country’s net income turns sharply negative, not when its position is significant; the United States still earns more abroad than it pays at home. Second, “Finance concentrates wealth.” Proper but progressive taxation of capital gains can be redistributed without dismantling the advantage. Third, “Manufacturing jobs have social value, finance lacks.” Agreed—which is why tariff revenue should be bundled with wage insurance and community college up-skilling rather than being treated as a stand-alone victory. Importantly, none of these objections dispute the mirror mechanism; they challenge its side effects. Addressing those effects directly is more coherent than construing the mirror itself as a problem.

Policy Blueprint: Target the Net, Not the Node

A mirror-account mindset suggests a different policy yardstick: aim for a stable net current-account balance rather than a zero goods balance. That means tolerating trade deficits as long as the investment-income surplus remains positive and systemic risk indicators—such as bank leverage, maturity mismatch, and cross-currency basis—remain within historical norms. Tax policy should favor outward foreign direct investment that yields sustained income streams while discouraging short-term portfolio hot money. Treasury should issue “counter-cyclical convertibles,” bonds that automatically extend maturity if the NIIP falls below a trigger. Above all, the next Congress should require the Congressional Budget Office to score major trade bills on their net current-account impact, not merely tariff revenue.

Seeing Both Pages Before We Turn the Sheet

The $918 billion trade deficit and the $856 billion surge in outward investment for 2024 are not competing headlines; they are columns A and B of the same story. Cleaving them apart has produced tariffs that hobble our comparative advantage while systemic risk metastasizes in the shadows of the capital account. The task ahead is not to chase a shrinking import bill but to harness the dividend that imports make possible—higher global earnings—and to recycle that dividend into education, resilience, and fairness. Once we learn to read both pages of the ledger in a single glance, the policy debate will shift from closing the gap to maximizing the returns on the capital surplus that mirrors it. That, not another tariff round, is the deficit conversation America needs in 2025.

The original article was authored by Charles Yuji Horioka and Nicholas Ford. The English version of the article, titled "A new modelling approach for evaluating the Trump tariffs," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.

References

Bank for International Settlements (BIS). 2025. “Quarterly Review: March 2025.” Bank for International Settlements.

Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA). 2025a. “U.S. International Transactions, 1st Quarter 2025 and Annual Update.” US Department of Commerce.

Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA). 2025b. “U.S. International Investment Position, Year 2024.” US Department of Commerce.

Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA). 2024. “U.S. International Trade in Goods and Services, Annual 2024.” US Department of Commerce.

Eichengreen, Barry. 2019. Globalizing Capital: A History of the International Monetary System. 4th ed. Princeton University Press.

Gourinchas, Pierre-Olivier, & Hélène Rey. 2024. “The Exorbitant Privilege Still?” Journal of Economic Perspectives 38 (2): 23–47.

Horioka, Charles Y., & Nicholas Ford. 2025. “A New Modelling Approach for Evaluating the Trump Tariffs.” VoxEU Column, Centre for Economic Policy Research, 28 June.

International Monetary Fund (IMF). 2025. “World Economic Outlook Database, April 2025.” International Monetary Fund.

Liberty Street Economics (LSE). 2025. “Why Does the U.S. Always Run a Trade Deficit?” Federal Reserve Bank of New York, 14 May.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). 2024. “FDI in Figures, April 2024.” OECD Publishing.

Reuters. 2025. “U.S. Current Account Gap Clocks Pre-2008 Crash Milestone.” 25 June