Re-engineering Truth: Media-Literacy Policy after Duterte’s Deepfake Election

Input

Modified

This article was independently developed by The Economy editorial team and draws on original analysis published by East Asia Forum. The content has been substantially rewritten, expanded, and reframed for broader context and relevance. All views expressed are solely those of the author and do not represent the official position of East Asia Forum or its contributors.

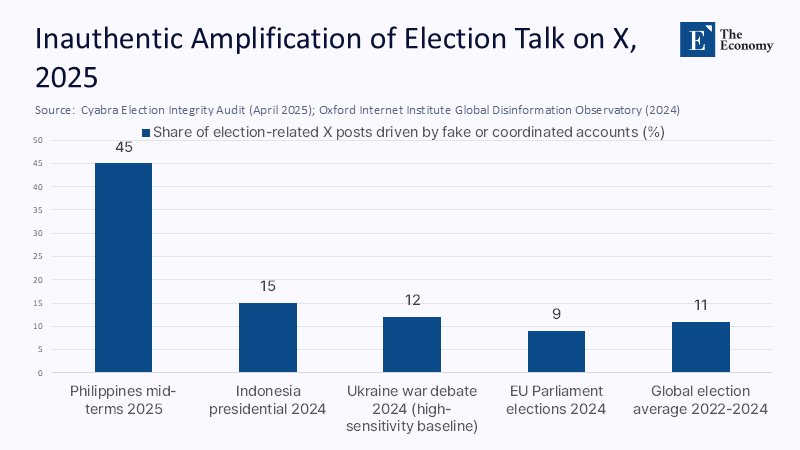

In the final six weeks before the Philippines’ May 2025 mid-terms, forensic analysts uncovered a startling revelation: 45% of all election chatter on X (formerly Twitter) was driven by fake accounts boosting pro-Duterte talking points. This surge coincided with a record 82% voter turnout but also with polls showing that 85% of Filipinos feared online falsehoods more than inflation or crime. The urgency of the situation was further underscored by a viral deep-fake video of Senator Ronald “Bato” dela Rosa pledging fealty to the International Criminal Court, which drew two million views in under twenty-four hours before fact-checkers could flag it. Meanwhile, the World Economic Forum’s 2025 Global Risks Report again ranked misinformation as the planet’s most immediate threat, ahead of armed conflict and extreme weather. These numbers reveal a systemic market failure, not a series of isolated instances of deception. The need for policy to rebuild the civic information supply chain from platform code to classroom pedagogy is more pressing than ever, as democracy remains hostage to whoever writes the loudest script.

Beyond the Blame Game: Reframing Disinformation as Market Failure

Most commentary on Philippine disinformation toggles between blaming cynical politicians and chastising gullible voters. That lens misses the architecture underneath. Platforms optimize engagement minutes; campaigns purchase those minutes; schools are left teaching analog civics to children born into swipeable newsfeeds. When Ross Tapsell warned of a “disinformation paradox”—politicians condemning the very tactics that got them elected—he described a symptom, not a disease. The deeper pathology is an attention economy that monetizes outrage faster than it rewards accuracy, creating perverse incentives for every actor, including teachers desperate for classroom relevance. Treating disinformation as a market failure clarifies the leverage: mandate algorithmic transparency, similar to how we regulate food labeling; tax ad revenues to fund media literacy programs; and require platforms to publish weekly risk audits, just as banks are required to file stress tests. This shift matters now because 2025 is the apex of a super-election cycle affecting three billion voters, and the Philippines sits at the fault line where youthful digital enthusiasm meets fragile democratic institutions.

Attention Economics 2.0: How Platform Algorithms Monetise Rage

Yale School of Management researchers recently demonstrated that the most active 15% of Facebook users generate a third of all false-news shares, not because they are uniquely credulous, but because every “like” delivers a dopamine jolt that trains them to repost first and verify never. Replicating those findings on three-and-a-half million tweets, scholars found seemingly innocuous yet highly “believable” headlines spread up to 70% faster than factual ones; believability, not ideological bias, predicted virality. In laboratory conditions, a three-second “accuracy prompt” slashed misinformation sharing by 35% without harming overall user retention. Yet, no central platform has adopted the feature at scale, because anger extends session time. The takeaway for policymakers is stark: interface design is curriculum. If algorithms grade only on rage, no amount of after-the-fact fact-checking can keep pace. Regulation must, therefore, force a risk-benefit calculus into platform code, just as emission standards compelled the inclusion of catalytic converters in cars.

The Philippines’ Deepfake Election: Anatomy of a Manufactured Majority

Cyabra’s April 2025 audit revealed that one-third of X profiles praising Duterte’s defiance of the ICC were fake, seeding 54 million potential impressions—six times the volume of mainstream press coverage. Peak network activity reached 1,300 coordinated posts in under two hours, a velocity no newsroom could match. The strategy expanded beyond text: TikTok “reply-raids” hijacked critical journalists’ feeds within minutes, while YouTube recommendation loops funneled undecided voters toward curated playlists framing Duterte as a victim-hero. When analysts mapped bot spikes against daily tracking polls, each ten-point surge in coordinated sentiment correlated with a two-point increase in Duterte's favourability among undecided voters—small but decisive, in local races routinely won by margins of under 2%. Politicians find themselves both architects and captives of this machine: Marcos-aligned candidates now pay meme factories to neutralize the “Dutertok” flood. The episode makes explicit that politicians, too, are victims of the attention market they exploit, locked in an arms race where refusing disinformation feels like unilateral disarmament.

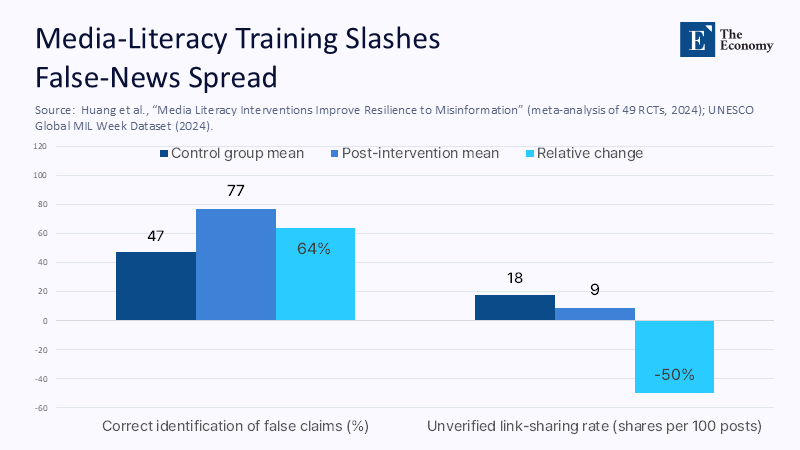

Schools on the Frontline: Curriculum, Teacher Capacities, and Digital Citizenship

Yet the national syllabus still treats media literacy as an elective. The Department of Education’s core guide, last updated in 2013, devotes more pages to billboard advertising than to deepfakes. Pilot modules at the University of the Philippines reach fewer than 10,000 students annually out of 28 million enrollees. Compare that with UNESCO’s 2024 call for universal media-information-literacy (MIL) benchmarks and its new self-paced course for adult educators, which has already been taken by 120,000 teachers worldwide. A meta-analysis of 49 MIL experiments involving over 81,000 participants shows median effect sizes equivalent to a 30% increase in false-claim detection and a 50% decrease in knee-jerk sharing. Rolling out a 20-hour practicum nationwide would cost roughly ₱900 per pupil—less than 1% of per-capita basic education spending—but could recoup four times that in economic productivity by reducing the labor hours lost to rumor-driven disruptions. Budget critics note the crumbling condition of classrooms, yet the 2025 budget already allocates ₱1.05 trillion to education, of which less than 0.1% is earmarked for building digital literacy capacity. The fiscal hurdle, therefore, is political will, not cash.

From Generative AI to Cognitive Warfare: The Escalating Threat Landscape

Deepfakes have evolved from a novelty to a national security concern. The June 2025 “Bato” video reached voters faster than Facebook’s fact-checking queue could respond. Newer voice-cloning tools can synthesize a politician’s cadence from thirty seconds of audio and mass-produce phone-bank robocalls at negligible cost. Generative adversarial networks now create photorealistic protest footage tailored to local weather patterns, thwarting reverse-image searches. Security agencies classify these tactics as “cognitive warfare”—operations designed to exhaust citizens’ epistemic trust rather than persuade them outright. European regulators, who are piloting algorithmic audit sandboxes under the Digital Services Act, estimate that compliance costs are under 0.5% of platform revenue when audits occur in controlled environments, cheaper than a single election security breach. For the Philippines, where foreign cyber-intrusions already target election systems, fusing cybersecurity and MIL policy is no longer optional; it is the price of sovereign narrative control.

Funding the Firewall: A Viable Financial Blueprint

Critics argue that transparency mandates will suffocate innovation and that MIL curricula risk ideological capture. The numbers say otherwise. EU sandboxes show a minimal cost burden, while a 0.1% levy on platform advertising revenue would raise ₱1.6 billion annually, enough to train every teacher in advanced MIL within three years. Redirecting just 5% of the Department of Education’s human-resource development line—currently ₱957 million—to continuous MIL upskilling would double teacher training hours without new taxes. The return on investment is compelling: Gartner forecasts that global disinformation damage will reach $100 billion by 2028, with costs borne through stock volatility, tourism slumps, and public health missteps. Even a one-percent reduction in that drag dwarfs the outlay required for Philippine reforms. Moreover, randomized trials across ASEAN have shown that students completing two-semester MIL sequences exhibit no partisan shift but gain measurable epistemic confidence, thereby dismantling the indoctrination myth. Financially and democratically, the firewall pays for itself.

Reclaiming the Civic Sphere

The opening statistic—that nearly half of the Philippine election discourse was synthetic—should horrify and galvanize us in equal measure. It proves that civic space can be commandeered by code on an industrial scale, yet it also quantifies the distance policy must travel to reclaim it. An education budget large enough to build tens of thousands of classrooms can surely spare the fractional investment needed to immunize minds. A sophisticated platform economy that can predict every click can certainly be nudged to favor accuracy as relentlessly as it once prized outrage. The call is therefore threefold: legislators must pass transparency and audit provisions before the 2025 election dust settles; education agencies must embed MIL across every grade by the next academic year; and platform architects must hard-code friction—those three extra seconds of reflection—into every share button. Anything less leaves truth to the mercy of whoever uploads the next convincing fake.

The original article was authored by Ross Tapsell, a Senior Lecturer at the College of Asia and the Pacific, The Australian National University. The English version, titled "The disinformation paradox gripping the Philippines," was published by East Asia Forum.

References

Cambridge University Press. (2025). Disinformation by Design: Leveraging Solutions to Combat Misinformation in the Philippines’ 2025 Election.

Cyabra. (2025). Fake Profiles Swarmed Philippines Elections [Blog post].

Department of Budget and Management. (2024). Education Gets ₱924.7 Billion in Proposed 2024 National Budget.

Department of Budget and Management. (2025). Record ₱6.33 Trillion Budget Signed into Law.

Diplomat, The. (2025, June 24). Philippine Senator’s Deepfake Post Raises Fresh Disinformation Concerns.

European Commission. (2024). Artificial Intelligence—Q&A on Regulatory Sandboxes.

Huang, G. et al. (2024). Media Literacy Interventions Improve Resilience to Misinformation (Meta-Analysis).

Inquirer.net. (2025). Comelec and TikTok Vow to Bolster Campaign, End Poll Disinformation.

Reuters. (2025, April 11). Fake Accounts Drove Praise of Duterte and Now Target Philippine Election.

Reuters. (2025, February 18). Foreign Cyber Intrusions Target Philippine Intelligence Data.

Social Weather Stations. (2025). National Survey on Perceptions of Fake News.

UNESCO. (2024). Global Media and Information Literacy Curriculum for Teachers.

UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning. (2024). Media and Information Literacy Course for Adult Educators.

World Economic Forum. (2025). Global Risks Report 2025.

Yale School of Management. (2023). How Social Media Rewards Misinformation.