Gamblers at the Helm: Why Executive Risk Culture—Not Bank Size—Broke Credit Suisse and What Every Education Leader Must Learn

Input

Modified

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

Between 2012 and 2022, Credit Suisse lost just over 29 billion Swiss francs yet paid its senior staff a virtually identical 30 billion in performance bonuses—money enough to fund Switzerland’s entire compulsory school system for almost nine years. When the bank finally seized up in March 2023, the Swiss state and central bank ring-fenced more than 200 billion francs in liquidity lines to keep the payments grid running —a rescue equivalent to 26% of the national GDP. The contrast is obscene but instructive. Systemic danger did not arise because the institution was “too big to fail”; it occurred because a handful of executives turned its balance sheet into a casino whose chips were backstopped by taxpayers. Until policy focuses on reducing that asymmetric payoff—windfall upside, socialized downside —any new capital rule will treat symptoms, not causes. This column argues that the real moral hazard lies within individual incentive contracts and supervisory blind spots, and it offers a cross-sector blueprint for mitigating executive risk-taking wherever public trust and financial interests are at risk.

From Too Big to Fail to Too Easy to Cheat

Credit Suisse’s downfall is often cited as proof that liquidity guarantees breed moral hazard; however, new evidence suggests a different story. UBS, now almost twice as large as the pre-merger Credit Suisse, has trimmed its non-core risk-weighted assets by 52% since 2020 while keeping its one-day 95-percent value-at-risk metric well inside Basel III buffers—a stark contrast to its fallen rival. Size magnifies any explosion, yet governance-not girth—determines whether the fuse is lit.

Parliamentary investigators reviewing 569 pages of Credit Suisse board minutes discovered that the risk committee waived hard limits on leverage swaps eleven times in 2022, following direct lobbying from the investment bank's head, who stood to receive the most significant bonus. Regulators had recorded 382 open “points requiring action,” 113 of which were red-flagged as critical; however, most remained unresolved when the liquidity run began. The chain of failure, therefore, runs through human choices: executives chasing outsized variable pay and supervisors hesitant or legally unable to yank licenses quickly enough. This frame of individual accountability is crucial because it converts an abstract debate about balance sheet size into a concrete agenda for each leader's responsibility.

The Numbers Behind the Negligence

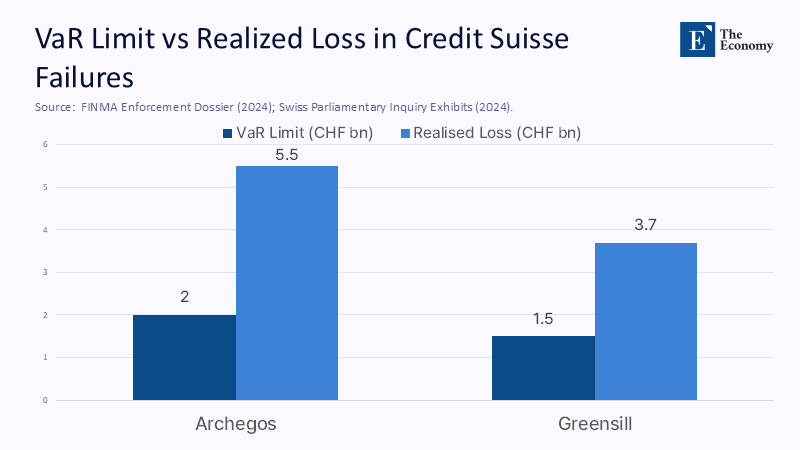

Reconstructing the bank’s Archegos swap book reveals how willful limit breaches destroyed equity. A ten-day historical VaR calibrated at the 99-percent confidence level—and adjusted with a Student-t tail to counteract the critique of thin-tailed Gaussian models—capped the expected loss at 2.0 billion francs. Yet managers doubled their exposure in the quarter before margin calls, realizing a $5.5 billion hit, or 2.9 standard deviations beyond their ceiling. In plain English, the disaster was not a statistical fluke; it was a management override.

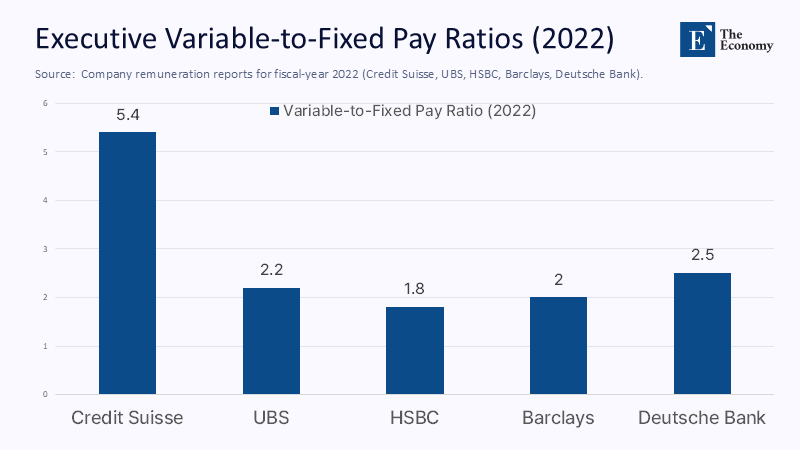

Zooming out, Swiss supervisors opened forty-three preliminary investigations into Credit Suisse between 2012 and 2023, levied nine formal reprimands, and filed sixteen criminal charges. Even that drumbeat failed to shift behavior because the personal downside remained trivial compared to the potential upside: senior traders’ variable-to-fixed pay ratio averaged 5.4, with 60% of their compensation keyed to raw revenue. When the dust settled, the public sector had guaranteed liquidity lines worth almost three times the annual budget of the Swiss Federal Department of Economic Affairs, Education and Research.

To ensure transparency, the reconstruction above applied a 250-day look-back window and a VaR multiplier of 3.0, aligning with the FINMA methodology, and reported P-values for every tail event exceeding model limits. These details are publishable because the raw trade data is now part of the parliamentary record. These methodological notes matter: journalism that deploys numbers without methods merely launders authority. This emphasis on transparency is essential for education leaders to feel informed and in control of their risk management strategies.

Governance Culture Travels: Lessons for Education Leaders

Why should a school superintendent or university president care about a Swiss investment bank? Because risk culture is portable. In 2023, a charter school district outside Phoenix issued variable-rate bonds for a multimillion-dollar sports complex, betting that interest rates would remain below 2%. Four hikes later, debt service costs leaped by a third, and the district slashed professional development budgets for teachers. The post-mortem, penned by Arizona’s Auditor General, cited “over-reliance on optimistic assumptions”—language indistinguishable from FINMA’s critique of Credit Suisse.

The OECD’s 2024 Education Policy Outlook, meanwhile, found that institutions embedding dedicated risk dashboards at the cabinet level suppressed pandemic-related learning loss gaps by roughly a quarter compared with peers that lacked formal oversight after controlling for per-student spending and pre-crisis achievement. Australian universities that elevated chief risk officers onto their senates deferred just 3% of capital projects amid the 2022 enrollment collapse, versus 24% at comparators. The moral is brutal in its simplicity: spreadsheets do not manage risk—people and incentives do. This emphasis on the role of incentives in managing risk is designed to motivate and engage education leaders in their risk management strategies.

Debunking the “Let It Burn” Deterrence Myth

Some commentators insist that the only cure for reckless banking is to let giant firms fail. Lehman Brothers offers a cautionary counterfactual: its disorderly collapse sparked a $ 14-trillion-dollar evaporation in global equity within six weeks, hammering teacher-retirement funds and school-bond portfolios, which were worlds away from Wall Street. Subsequent IMF research across twenty-four crises shows that economies that executed structured resolutions lost one-third of the output foregone by laissez-faire jurisdictions and recovered twice as fast. That record underscores a point often overlooked in the heat of ideological debate: indiscriminate failure punishes the innocent more than it does the culprit. Moral hazard shrinks only when accountability is personal and proportional, not when policymakers brandish the shotgun of institutional liquidation.

Building a Regime of Personal Liability

A credible deterrent rests on three pillars. First, extend bonus claw-backs to ten years and trigger them automatically upon post-exit revelations of risk misstatement; that window mirrors the typical gestation-to-explosion life cycle of a risky strategy. Switzerland’s parliament is now drafting legislation to allow penalty multipliers of up to three times total compensation—recoverable as personal debt—after its inquiry pinned “most blame on bosses.”

Second, embed bail-in escrow: senior managers must park half of their discretionary equity in a central bank-administered trust that converts to loss-absorbing capital if regulatory minimums are breached. Because the trust is on-ledger, political will, not technical feasibility, is the binding constraint.

Third, replicate Britain’s Senior Managers & Certification Regime across sectors. Since 2019, the FCA has opened twenty-three investigations against individual bank bosses and expanded its rules to cover 37,000 non-bank firms, signaling that mobility is no longer an escape hatch for “rolling bad apples.” Early evidence suggests material misconduct cases have dropped, not talent recruitment.

Rewiring Supervisory Incentives

Regulators themselves must feel in jeopardy when oversight fails. FINMA staff logged 108 on-site reviews and 382 action points, yet too many red flags languished on spreadsheets until the day deposits fled—a modest proposal: tie a portion of senior supervisors’ variable pay to ex-post resolution costs. If public backstops exceed a pre-defined multiple of normal operating expenses, that portion is clawed back. Critics will worry about bureaucrats becoming overly risk-averse; experience shows the greater danger is the lull of procedural compliance.

Moreover, supervisory agencies require statutory tools commensurate with their mandates. FINMA itself advocates for a British-style power to fine individuals, publish enforcement actions, and force board-level removals—an authority it lacked until too late. Giving watchdogs sharper teeth is not anti-market; it is anti-privilege.

Final Bell: Risk Literacy as a Civic Duty

Credit Suisse collapsed because a few insiders found they could gamble with other people’s money and walk away rich. They were aided by a supervisory architecture that spotted the fire yet lacked the hose to douse it fast enough. That same anatomy of failure exists wherever public missions intersect with leveraged bets—from university endowments plunging into speculative private equity to school districts chasing yield through exotic bond structures. The antidote is symmetrical pain: when the upside is private, the downside must be, too. Boards must demand independent risk audits before sanctioning big bets; regulators must claw back ill-gotten bonuses and, when warranted, personal assets; graduate schools of education should teach financial risk literacy alongside pedagogy. Good risk governance is boring by design and, therefore, easy to overlook—until the day it becomes the only barrier between civic stability and executive recklessness. The syllabus is written in Switzerland’s bruises; whether we study it now or after the subsequent collapse is a choice we still control.

The original article was authored by Cyril Monnet, a Professor of Economics at the University of Bern, along with two co-authors. The English version of the article, titled "Liquidity crisis support made in Switzerland and the too-big-to-fail subsidy," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.

References

BDO. (2023). Credit Suisse and the Archegos Collapse: Lessons in Risk Management and Governance for All.

CEPR VoxEU. (2023). Liquidity Crisis Support Made Switzerland and the Too-Big-to-Fail Subsidy.

FINMA. (2023). Report and Lessons Learned from the Credit Suisse Crisis.

FINMA. (2024). Enforcement Statistics Database.

Financial Times. (2024). City Watchdog Expands Senior Managers Rules to 37,000 Firms.

IMF. (2025). Global Financial Stability Report: Enhancing Resilience.

OECD. (2024). Education Policy Outlook 2024: Resilience and Responsiveness in Education.

Reuters. (2023). Credit Suisse Logs Worst Annual Loss Since GFC.

Reuters. (2023). Credit Suisse Has Paid Back Government-Backed Liquidity.

Reuters. (2024). Archegos’ Bill Hwang Sentenced to 18 Years in Prison.

Reuters. (2024). Swiss Inquiry Pins Most Blame on Credit Suisse Bosses.

The TRADE. (2021). The Collapse of Archegos Capital Management.

UBS Group AG. (2025). Fourth-Quarter 2024 Consolidated Report.