Input

Changed

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

In an economy starved of growth, the unintended consequences of legal flexibility have become apparent. Once hailed as a leap that would make hiring easier, the Italian Jobs Act has deepened the economic penalty of being dismissed and intensified the cultural stigma that has followed displaced workers for years. This analysis underscores the need for reforms that address these issues and pave the way for positive change.

Deregulation without Demand: The Central Misfire

When lawmakers in Rome transposed American-style “employment-at-will” logic into the 2014-15 Jobs Act, they imagined a virtuous circle: cheaper dismissals would reduce firms’ fear of back-firing hirings, vacancies would proliferate, and Italy’s chronically high unemployment would begin to melt away. Yet legislative dreams collided with macroeconomic reality. Between 2011 and 2024, Italian GDP expanded at an anemic 0.2% a year, less than one-fifth of the euro-area average. ISTAT’s spring 2025 update has already trimmed next year’s forecast to 0.6%, while the IMF’s Article IV mission pegs growth at only 0.4%, insufficient to stabilize the public debt ratio. Without fresh demand, firms used the new latitude not to expand payrolls but to shed risk, exposing employees to the chill of a labor market in which vacancies were scarcer than ever since the 1990s.

The harsh arithmetic of Okun’s law illustrates the bind. Across the OECD, a one-percentage-point rise in real GDP typically cuts unemployment by roughly 0.3 points. Recent econometrics show Italy’s elasticity hovers nearer –0.1. Put differently, Rome would need triple the growth of its peers to achieve the same reduction in joblessness. In such conditions, weakening protection does not lubricate reallocation; it manufactures casualties.

A Culture of Permanenza Meets Easy Exit

Beyond meager demand, Italy carries a cultural inheritance that magnifies dismissal costs. Career ladders remain dominated by seniority; promotions still depend on tenure, and a curriculum vitæ with unexplained gaps is often viewed as a red flag, not a sign of adaptability. In that milieu, the Jobs Act rewired employer heuristics. Once dismissal became cheaper, being dismissed became a louder signal of “low match quality.” Employers, free to prune payrolls at controlled cost, began to treat a previous redundancy as a negative productivity cue—deepening what labor economists call state dependence. An INET Oxford–Bank of Italy panel of 450,000 displaced workers finds that post-reform, two-thirds of the variance in re-employment probability is now explained by prior unemployment status, double the share before 2015. Italy has moved from a labor market that once tolerated short bouts of frictional unemployment to one that brands them as lasting blemishes.

The Numbers Beneath the Headlines

Superficially, the Jobs Act seems vindicated. The national unemployment rate slid to 5.9 percent in April 2025, its lowest since 2007, and youth unemployment dipped under 20 percent for the first time in a generation. Yet these aggregates mask a darker core. During the same twelve-month window, the inactivity rate climbed to 33.2 percent, the second-worst in the eurozone, and total hours worked fell despite a modest rise in headcount. Companies are hiring more people but for fewer hours and shorter contracts, an archetype of precarious employment.

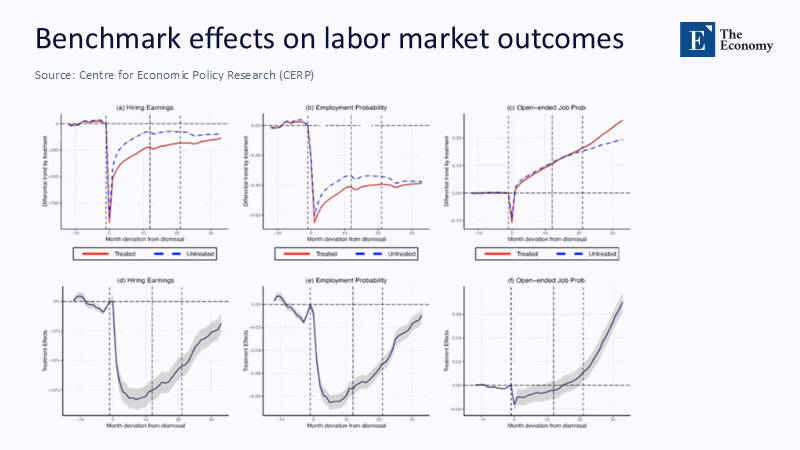

Administrative tax files add texture. For workers dismissed after 2015, median first-year earnings plunged 27%, and five years remain 11% below pre-layoff levels. A stacked-event study by CEPR attributes nearly four percentage points of that additional scarring to the Jobs Act, net of business-cycle effects.

The figure lays bare a structural fracture: twelve months after dismissal, treated individuals still earn about €250 per month less than their pre-reform twins, and their employment probability remains roughly three percentage points lower. Moreover, panel (f) shows that the likelihood of landing an open-ended contract only overtakes the pre-reform benchmark after two and a half years, underscoring how the promise of rapid matching morphed into drawn-out limbo.

Heterogeneity: How the Shock Plays Out by Separation Type

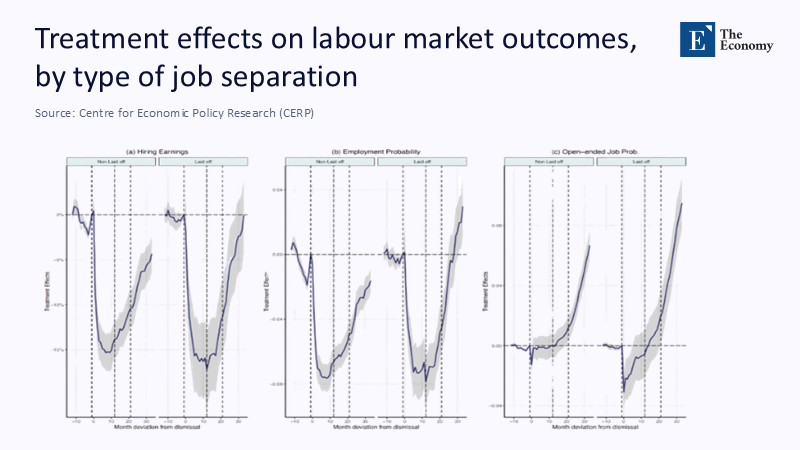

The impact of the Jobs Act is not uniform across all workers. Those who are let go through mass-layoff procedures, often older and higher-paid, face more severe penalties than those who leave via non-layoff separations such as mutual consent.

The graph illustrates a stark dualism: laid-off workers trace a deeper canyon and a more prolonged climb-out. Their earnings bottom at –18% around month 12 and only brush zero after month 32; non-layoff exits, by contrast, begin to heal after year one. Policymakers who imagined that lower firing costs would be neutral across separation types overlook how collective redundancies transmit a more toxic signal than negotiated exits—particularly in a labor culture already allergic to résumé gaps.

When Growth Is Too Slow to Absorb Churn

Why the sluggish rebound? Because the demand side is starved. Between 2015 and 2024, the economy added an average of 85,000 net jobs annually—one-quarter of the tally achieved in the 1990s. Micro-enterprises, representing over 90% of all firms, used the Jobs Act’s calibrated severance schedule to shed expensive senior staff while holding back on replacements until orders arrived. Orders, however, never picked up in scale. Without a vacancy flow, each redundancy becomes a zero-sum game: one worker’s exit is rarely another worker’s entry.

Italy’s aging curve compounds the shortfall. The OECD forecasts a 1.5-million decline in the working-age population by 2030. Shrinking cohorts mean firms face little competitive bidding for labor; they invest in automation rather than fight over recruits, hardening the tunnel effect seen in Figures 1 and 2.

The Hidden Health Bill

Dismissal costs extend beyond pay slips. National health survey micro-tables reveal a six-percentage-point jump in depressive symptoms among those dismissed in the previous year, double the EU average. Self-reported hypertension and insomnia also climb. Severance cheques cushion the initial shock, but the lingering uncertainty—illustrated by earnings gaps that persist for years—feeds chronic stress. Public health systems eventually absorb the bill through more visits, higher pharmaceutical subsidies, and reduced preventive care adherence. The Jobs Act thus shifted costs from corporate balance sheets to taxpayer-financed outlays, another unintended redistribution.

International Benchmarks: Why Copy-and-Paste Fails

Italy is hardly alone in labour-law experimentation. Spain’s 2012 liberalization, often cited by Jobs Act architects, coincided with a six-point VAT cut, €5 billion in active-labor-market programs, and a surge in ECB-supported credit. France’s 2017 Ordonnances arrived amid an investment boom sustained by negative real rates and a payroll-tax rebate scheme. Italy’s reform had no comparable macro tailwind. A Eurostat-based counterfactual suggests that if Rome had matched Spain’s 1.8% average growth between 2014 and 2019, it could have created roughly 420,000 extra jobs, enough to absorb every redundancy issued under the new regime and still leave a cushion. The lesson: institutional imports succeed only when paired with supportive macro environments.

Green Shoots—But Only If Conditioned

There is, nevertheless, a faint glimmer. Industrial output ticked up 1% in April 2025, led by renewable-energy equipment. The uptick coincides with the roll-out of the EU’s €190-billion Recovery and Resilience Facility. In principle, capital expenditure in green infrastructure could birth a wave of middle-skill employment akin to Germany’s solar boom in the mid-2000s. Yet Italy’s history warns that capital-intensive surges may boost value-added while trimming head count. To turn green capex into green jobs, Rome must attach hiring conditions: for every €5 million of subsidized investment, at least one apprenticeship-to-permanent pathway. , The mini-boom will feed equipment suppliers in Bavaria or Shenzhen without such linkages while Italian workers remain in limbo.

A Blueprint for Re-Sequenced Reform

Rolling back the Jobs Act would be a political dead end and an economic time-warp. Instead, Italy must re-sequence flexibility behind demand support and align dismissal penalties with cyclical slack. Four interlocking pillars emerge:

- Demand-linked depreciation. Offer accelerated depreciation only on the share of capital corresponding to net new hires, denying the fiscal windfall to downsizing firms.

- Counter-cyclical severance. Replace the current 24-month cap with a sliding scale: when provincial unemployment exceeds a 7% threshold, the ceiling rises automatically, nudging firms to re-deploy staff internally rather than externalize shocks.

- Portable skills passports. Scale up the Lombardy pilot of blockchain-verified training credits. Passports neutralize stigma and shorten the tunnels seen in Figures 1 and 2 by letting candidates showcase certified learning rather than tenure.

- Wage-growth tax credits tied to training. Redirect part of the EU green-transition budget to credits that reimburse firms for the first €3,000 of wage growth per worker, provided employees log 100 hours of certified up-skilling within 12 months.

These measures tackle the Jobs Act’s core blind spots: they restore demand, cushion workers when demand is weak, and erode the information asymmetry that converts a dismissal into a permanent scar.

Reform as Translation, Not Transplant

Italy’s experience crystallizes a broader maxim for policymakers: flexibility is an ecosystem property, not a statute. American fluidity works because vacancy creation is relentless—3% of jobs are turned over monthly. Italian turnover rarely cracks 1%, even during booms; when growth stalls, the conveyor belt grinds to a halt. Importing dismissal rules without exporting the vacancy engine misaligns incentives and multiplies risk.

The Jobs Act was conceived as a liberation, freeing managers to hire and fire in pursuit of productivity. In a context of demographic contraction and demand drought, it became an accelerant of inequality, raising the lifetime earnings penalty of job loss to record heights and embedding cultural stigmas more deeply than before. Italy’s predicament thus offers a cautionary tale but also a roadmap. Context-sensitive design—demand first, counter-cyclical safeguards second, cultural rewiring throughout—can revive the promise of mobility without resurrecting the rigidity of the past. The actual cost of delay is paid not in parliamentary scorecards but in the silent arithmetic of workers who, years after a redundancy letter, still earn less, sleep worse, and wait longer for the second chance the reform was meant to guarantee.

The original article was authored by Marco Francesconi and Daniela Sonedda. The English version of the article, titled "Employment protection legislation reforms and the rising cost of job loss," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.

References

Bertheau, P. et al. (2025). “Does Weaker Employment Protection Lower the Cost of Job Loss? Evidence from Italy.” CEPR Discussion Paper DP 20278.

CEPR (2025). “Employment Protection Legislation Reforms and the Rising Cost of Job Loss.”

IMF (2025). Italy: Staff Concluding Statement of the Article IV Mission.

INET Oxford (2024). “Traps and Tunnels in Italy’s Labour Market.”

ISTAT (2025). “Italy April Unemployment Falls to 5.9 %.” Reuters dispatch.

ISTAT (2025). “GDP Growth Forecast Revision.” Reuters dispatch.

OECD (2024). Economic Surveys: Italy.

OECD (2013). The 2012 Labour-Market Reform in Spain.

OECD (2017). Economic Survey: France.

ResearchGate (2024). “The Pyramid of Okun’s Coefficient for Italy.”

Reuters (2025). “Italy Industry Output Rises in April.”