Europa's Carbon Ambition in a Fractured World: Why Brussels Cannot Regulate Alone

Input

Modified

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

Six percent. That is all the carbon dioxide the entire European Union added to the atmosphere last year, down from nearly 10% at the turn of the millennium. Yet, Brussels now pays the world's highest carbon price, hovering close to €90 a tonne, and has drafted a new border levy expected to raise about €12 billion annually by 2030. Meanwhile, the same ships that unload low-carbon European steel reload with higher-carbon Chinese solar panels forged in coal-fired foundries—and Europe buys them anyway. The imbalance is stark: €89 billion in carbon-intensive goods entered the single market in 2024, embedding roughly 350 million tonnes of "outsourced" emissions, almost equivalent to Germany's entire domestic total. Far from proving European irrelevance, the statistic highlights the limitations of governing a global atmosphere from a single regional capital. Climate leadership is authentic, but the leverage to reshape supply chains, nudge superpowers, or set worldwide norms is shrinking faster than the glaciers Europe seeks to protect.

From Pillars to Picket Lines: Reframing Europe's Carbon Gambit

The VoxEU's four-pillar strategy—carbon-pricing alliance, shared border mechanism, large-scale finance, and debt swaps—casts Europe as the convenor of a pragmatic, plurilateral coalition. This strategy, proposed by the authors, rightly abandons the UN's requirement for unanimity. Yet, they still presume that the European Union, cushioned by a multilateral legacy, can rally the hesitant and the hostile. My point of departure is simpler: what if the architect lacks the steel, literally and figuratively, to finish the roof? Europe remains the planet's premier regulatory laboratory, but the machinery inside that lab is shrinking. The United States is unbolting its climate apparatus, China is erecting a parallel one, and Japan is hedging. In that context, the four pillars read less like foundations than picket lines—markers of where Brussels must stop pretending and start renegotiating its role.

Why revisit the argument now? Because 2025 is a pivotal year in which technology costs, trade politics, and alliances all shift away from Brussels. The European carbon price no longer intimidates rivals; it spurs them to deepen subsidies at home and tariffs abroad. China's battery champions under-cut European packs by 25% even after the Emissions Trading System surcharge. Washington, having briefly unleashed the Inflation Reduction Act, now moves to repeal most of its credits, threatening $132 billion in projects. Japan's draft levy, scheduled no earlier than 2026, exempts two-thirds of industrial emissions. When key partners leave the stage or read a different script, Brussels must admit the play has changed. Reframing is not a rhetorical flourish; it is a survival strategy for European climate diplomacy.

Leverage by the Numbers: Carbon Prices, Trade Flows and Emissions Shares

Start with brute arithmetic. The EU-27 generated just 6.1% of global greenhouse gas emissions in 2023, yet accounted for roughly 16% of the world's GDP and 18% of merchandise imports.

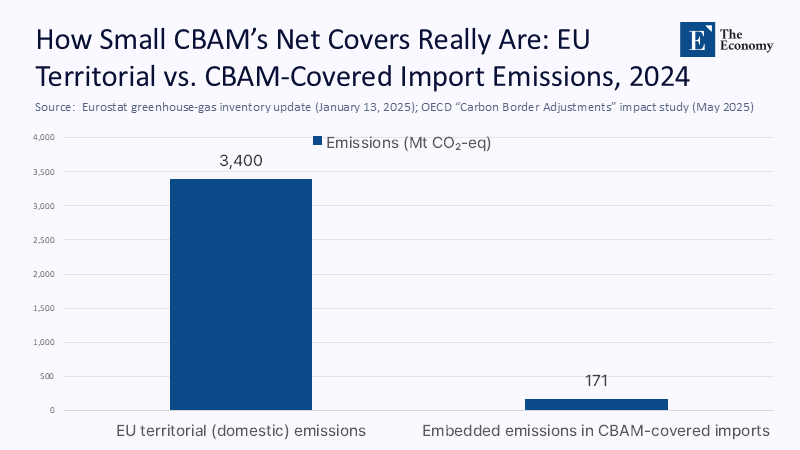

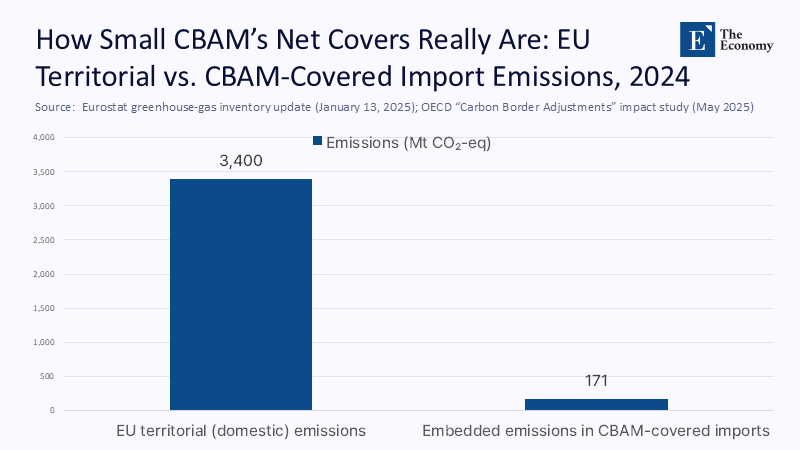

At first glance, that is leverage: Europe buys more than its weight and pollutes less. However, imports are fragmented across thousands of suppliers whose more substantial incentives usually lie in Beijing, Washington, or Mumbai. At full strength, the forthcoming CBAM surcharge would affect only around €89 billion in trade, equivalent to 0.04% of global manufactured exports. Even within Europe, the measure covers products that represent barely a quarter of consumption-based emissions, leaving three-quarters offshore, untaxed, and largely untracked. Scale matters, and Europe's is insufficient.

Put differently, Brussels seeks to steer a $105 trillion world economy with a compliance lever smaller than the annual revenue of a single Fortune 50 firm. This 'compliance lever' refers to the influence or control that Brussels has over global climate policy, which is significantly smaller than the economic power it wields. Compare that with China's projected $450 billion in solar investments this year or with the $3.3 trillion total global energy expenditure the IEA forecasts for 2025, which is nearly twice Europe's outlay. Within the bloc, momentum is slipping: 2024 clean-energy investment fell 6.8%, even as global spending rose 11%, with grids and industrial decarbonization leading the retreat. The IEA is blunt: China now invests twice as much in energy as the EU and almost as much as the EU, United States, and Europe combined. Numbers rarely lie, but this set suggests that Europe no longer moves markets on its own.

Supply Chains Entangled: Manufacturing Dominance and Strategic Vulnerability

If the financial gap appears daunting, the physical gap is even more daunting. By 2024, China is expected to supply 95% of the polysilicon ingots and wafers that become solar panels, a choke point so acute that one Xinjiang factory produces one-seventh of the global output. In batteries, the picture is similar: Chinese plants produced 1.17 TWh of cells last year—76% of global production—and the giants CATL and BYD alone could power every electric vehicle sold in Europe twice over. Europe's Critical Raw Materials Act promises diversification; however, on the announced timelines, the EU is expected to cover at best 10% of its cathode demand domestically by 2030. As AMG Lithium's chief executive warned this week, "We may as well be a province of China" if dependencies deepen further.

The four-pillar prescription assumes supply chains are elastic, ready to migrate once carbon costs realign incentives. Reality is rigid. The price gap between European and Chinese solar modules widened to six euro cents per watt in 2025, driven by subsidized energy and credit in China. Before CBAM takes effect, the value-added margin on a European battery pack is already negative unless factories operate at 9% utilization—impossible given current demand. Brussels ultimately pays firms to build plants that will still import most of their inputs from Asia. A regime that taxes carbon at the border but implicitly untaxed it upstream is not a virtuous loop; it is a Möbius strip, turning back on itself indefinitely.

The Carbon Club That Wasn't: Allies, Incentives, and Realpolitik

Advocates place faith in a future "climate club," a coalition of major economies agreeing on minimum prices and mutual trade defense. Yet club formation presupposes stable members. The United States, once a putative co-founder, is dismantling the Inflation Reduction Act; a Senate bill would erase more than $132 billion in credits and jeopardize 120,000 jobs. Simultaneously, the Environmental Protection Agency has requested that the White House reconsider its endangerment finding, which threatens federal authority over greenhouse gases. Japan's draft carbon price starts below ¥300 a tonne—less than one-fifth of the EU rate—and shields its heaviest exporters. Clubs built on such shifting sand will not hold a World Cup let alone a warming planet.

What alternatives exist? One is to recognize that carbon diplomacy now resembles post-Bretton Woods monetary talks: plurilateral, interest-driven, and anchored by swing states, not superpowers. Europe could court Mexico, Turkey, Indonesia, and South Africa—economies whose combined exports to the EU already exceed those of Japan—to pilot verifiable sectoral deals in steel, aluminum, and fertilizers. Another is to pivot from punitive border taxes to bonus–malus procurement: guaranteeing green-premium contracts for suppliers that meet European benchmarks, wherever they are located, funded from recycled ETS revenue. Such mechanisms need neither Washington's assent nor Beijing's goodwill; they demand European political courage and administrative stamina. They also reward technology diffusion, a variable missing from CBAM's ledger but present in every successful environmental treaty, from the Montreal Protocol (the ozone treaty) to the Marine Sulphur Treaty.

Classrooms, Boardrooms, Ministries: Translating Macro Stalemate into Micro Action

For educators, the lesson is clear: global climate governance begins inside domestic institutions. Engineering schools that teach life-cycle modeling yet ignore supply-chain geopolitics graduate half-ready professionals. Sustainability curricula must incorporate trade law, critical mineral economics, and comparative policy analysis to address these issues effectively. When a European solar project manager outsources module procurement to the finance desk, the gap is not technical but epistemic. Embedding full-cost carbon accounting exercises into capstone courses—and inviting procurement officers from African utility-scale ventures to guest-teach—creates graduates who understand why a border levy alone cannot rescue an industry.

Administrators and ministers can act even sooner. Public-sector buyers—such as school districts, hospital trusts, and municipal transit agencies—command billions of dollars in annual purchasing. Requiring scope-three disclosure as a tender condition would push carbon transparency deeper than CBAM can reach. In parallel, ministries should pilot carbon-content labeling for consumer imports, piggybacking on the EU's Digital Services Act. Such steps anchor climate action in citizen-facing bodies, reduce the democratic deficit critics exploit and amplify Europe's remaining soft power: regulatory capacity coupled with consumer trust.

Answering the Skeptics: Leakage, Innovation, and Moral Authority

Sceptics voice three familiar objections. First, CBAM will merely reroute trade through third countries. Yet early data from the mechanism's transition phase show EU fertilizer imports down 26% and aluminum down 4%, with no equivalent spike through Singapore or Morocco. Second, they warn of retaliatory tariffs, but the WTO has logged just four formal complaints since CBAM's adoption, none escalating beyond consultations, fewer than the 2012 solar-panel dispute. Third, they claim Europe's moral authority evaporates as its emissions fall. Authority, though, derives from policy credibility: a functioning ETS, transparent registries, and an independent judiciary still outperform the alternatives.

A deeper objection is that Europe cannot depend on Chinese supply chains while claiming autonomy. History suggests dependency can be a ladder rather than a leash when paired with industrial discipline. In the 1970s, Japan imported 99% of its oil yet built the world's most efficient car fleet; in the 1990s, South Korea relied on U.S. chip designs but turned Samsung into a titan. Europe will replicate that arc only by trading purity tests for trajectory management: co-financing gigafactories, expanding grids, and underwriting demand for green-premium steel. Whether those factories use Chinese equipment in year one is less important than whether they are competitive by year ten.

From Ambition to Realism: Recalibrating Europe’s Climate Leverage

Return to the opening statistic: six percent. Europe's share of emissions is expected to dip below 5% within the decade, but its responsibility will not. The bloc can still shape global norms—if it recognizes that regulatory finesse is not a substitute for raw power. A credible strategy begins at home: embedding supply-chain literacy in education, recycling ETS revenues into performance-based procurement, and courting mid-sized partners willing to trade access for ambition. None of this requires waiting for Washington's signature or Beijing's consent; all of it demands that Brussels abandon the fantasy of solitary global regulation and embrace the slower craft of coalition-building from the middle out. Do so, and the figure framing future debates may no longer be 6% emitted but 40% avoided because Europe chose realism over rhetoric.

The original article was authored by Jean Pisani-Ferry, a Senior Fellow at Bruegel, along with two co-authors. The English version of the article, titled "Global action without global governance: A four-pillar strategy for climate and nature," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.

References

Birol, F. (2025). Global Energy Investment set to rise to $3.3 trillion in 2025. International Energy Agency.

Crippa, M. et al. (2024). GHG Emissions of All World Countries – 2024 Report. European Commission Joint Research Centre.

European Commission. (2023). Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism – Taxation and Customs Union.

Financial Times. (2025). European investment in the energy transition is stalling.

Guardian, The. (2025). EU may as well be "province of China" due to reliance on imports, says industrialist.

International Energy Agency. (2022). Solar PV Global Supply Chains – Executive Summary.

International Energy Agency. (2024). The Battery Industry Has Entered a New Phase.

Narloch, U. (2025). EU imports of CBAM goods in global supply chains. CO2 IQ.

Patey, L. (2024). The European Union can go green and lower dependencies on China. Danish Institute for International Studies Policy Brief.

Pisani-Ferry, J., Weder di Mauro, B., & Zettelmeyer, J. (2025). Global Action without Global Governance: A Four-Pillar Strategy for Climate and Nature. VoxEU.

Reuters. (2024). Japan's draft climate strategy spurs calls for bolder cuts in carbon emissions.

U.S. Washington Post. (2025). Biden's climate law boosted red states. Their lawmakers are now gutting it.Walsh, J. (2025). EPA asks White House to bless rollback of key climate finding. PoliticoPro.