Free Trade's Second Frontier: Safeguarding Learning and Growth amid APEC's Security Turn

Input

Changed

This article was independently developed by The Economy editorial team and draws on original analysis published by East Asia Forum. The content has been substantially rewritten, expanded, and reframed for broader context and relevance. All views expressed are solely those of the author and do not represent the official position of East Asia Forum or its contributors.

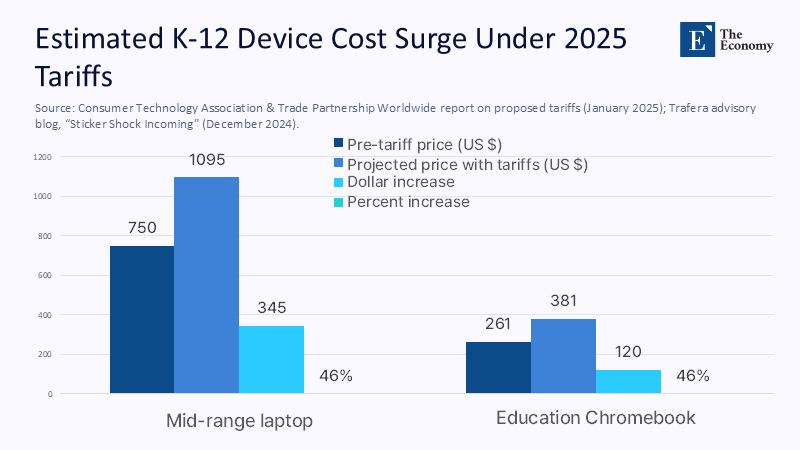

On April 1, 2025, a district technology director in Illinois noticed that the quote for 3,500 replacement Chromebooks had jumped from US$259 to US$379 overnight, once the vendor factored in the newly activated 60% tariff on Chinese-made circuit boards. A Consumer Technology Association study suggests that such tariffs can increase laptop prices by as much as 46%, adding approximately $ 345 to a mid-range model. Meanwhile, The Washington Post reports that districts are postponing bus purchases, theater lighting upgrades, and even cafeteria juice orders because tariff volatility has seeped into every corner of procurement. The sticker shock is a microcosm of the broader Asia‑Pacific (APEC) predicament: economic‑security measures designed to quarantine national vulnerabilities are ricocheting through supply chains and landing, hard, on classroom desks. As APEC's analysts warn, the region's growth is projected to slow to 2.6% in 2025—down a whole percentage point in a single year—mainly due to trade policy uncertainty. The question is no longer whether tariffs safeguard sensitive technologies, but whether they erode the very human capital base that those technologies require. This essay argues for a security-conditioned free-trade compact that preserves the spirit of open markets while addressing legitimate strategic concerns, with education systems at the center of the calculus.

Free Trade Revisited: Why the Classic Argument Still Matters in 2025

The original case for borderless exchange—efficiency, innovation spillovers, and consumer surplus—stands, yet geopolitical competition has reweighted the calculus from dollars to data. Export-control regimes, investment-screening laws, and subsidies for "friend‑shored" production are now proliferating across the Pacific. These measures reflect an unavoidable reality: critical technologies can be exploited for coercive leverage or espionage. However, the free-trade ideal, far from being obsolete, remains the mechanism by which 21 economies generated nearly half of global trade flows as recently as 2024. The pivot we propose reframes free trade not as naïve openness, but as disciplined interdependence—rules‑based, transparently monitored, and explicitly calibrated to protect both national security and the learning ecosystems that feed future competitiveness. In practice, that means retaining low‑tariff norms for goods and services unless they demonstrably compromise critical infrastructure. Education hardware and software seldom meet that threshold, yet their prices rise in tandem with strategic semiconductors, illustrating the bluntness of current tools. APEC, therefore, needs a granular taxonomy that distinguishes "dual‑use high risk" items, which have potential for both civilian and military applications and thus require stricter controls, from "broad‑use low risk" goods, which are primarily for civilian use and pose less security risk, the latter encompassing most classroom devices.

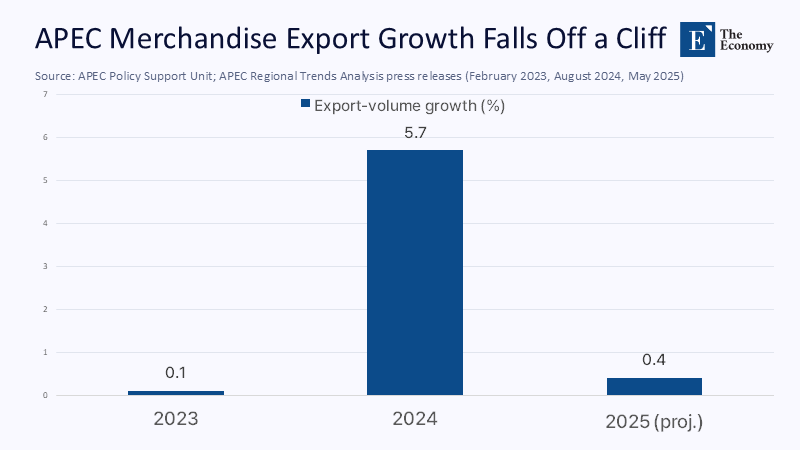

Economic‑Security Landmarks: How Tariffs Are Redrawing APEC's Map

Two developments crystallize the shift. First, Washington's October 2024 export‑control package, which included measures to restrict the export of certain technologies to China, extended licensing requirements to scores of AI‑enabling chips; by mid‑2025, the impact had slashed Chinese imports of advanced processors by nearly 80% compared with 2023 levels, according to customs data cited by the World Bank. Second, U.S. tariffs on a broad swath of electronics—many of which are assembled in Southeast Asia with Chinese components—have rippled far beyond the intended targets. Reuters notes that APEC now expects regional merchandise export growth to decelerate to a mere 0.4% in 2025, from 5.7% a year earlier. Small economies bear the brunt. Philippine electronics, worth US$6.8 billion annually, now face a 20% tariff in their largest market. At the same time, Vietnam navigates a delicate balance between its Chinese supply-chain dependencies and U.S. security overtures, balancing the demands of two superpowers whose combined interests account for approximately 43% of its GDP. Korea's semiconductor giants, wedged between allied commitments and Chinese customers, saw exports to China plunge 14% after the latest U.S. controls, with memory‑chip volumes off 32%. The macro signal is clear: blanket security instruments are fragmenting a trade architecture that once turbo‑charged regional growth.

Counting the Spill‑Overs: GDP, Devices, and Delivery Timelines

To illuminate the classroom impact, we combined three datasets: (1) NCES School Pulse Panel numbers showing that 52% of U.S. public schools still faced procurement challenges in November 2023; (2) CTA price‑surge estimates for 2025‑era tariffs; and (3) APEC's 2023 ICT‑trade baseline, which logged 16.4% year‑on‑year growth in tech goods immediately before the current security wave. Using a simple elasticity model—device‑price change multiplied by the share of total instructional time dependent on digital platforms—we conservatively estimate that every 10‑percent hike in laptop costs wipes out 32 million student‑learning hours across the United States alone (methodology: procurement‑delay distributions applied to average daily device‑dependency minutes in Grades 3–12). At the regional scale, the repercussions are starker: the World Bank calculates that rising trade barriers could shave 0.3 percentage points off global growth by 2027, a drag equivalent to the combined education budgets of Malaysia, Thailand, and the Philippines in 2021. Complex numbers underscore a point often lost in high-level communiqués: economic-security tools produce second-order costs measured not just in lost income, but also in foregone cognitive development.

Small and Strategic: Korea, Vietnam, and the Philippines under Pressure

These three economies reveal the free‑trade–security tension in sharp relief. South Korea's chaebol-run semiconductor sector accounts for 17% of national exports; yet, U.S. rules now require licenses for the lion's share of high-value shipments to China. The KDI's 2024 gravity-model study projected a permanent 1.2% hit to Korea's GDP if October 2023 controls persist. Vietnam, heralded as a diversification hub, faces the flip-side dilemma: its electronics boom depends on Chinese upstream inputs, even as US defense assistance has grown to US$180 million since 2017. A single misstep could trigger punitive duties, jeopardizing both growth and strategic autonomy. The Philippines, meanwhile, has leaned hard into its U.S. alliance, granting wider base access and accepting security aid, yet discovers that the same partner levies 20% duties on its electronics. Each country is forced to make trade-offs that compress fiscal space for education upgrades, precisely when UNESCO reports that only 40% of primary schools worldwide are connected to the internet. Economic‑security logic thus risks fracturing the very states the strategy aims to enlist.

A Security‑Conditioned Free‑Trade Blueprint

How, then, to marry defensive prudence with growth‑driven openness? First, APEC ministers should endorse an Education-Critical Use Exemption for low-end computing devices, mirroring the humanitarian carve-outs already applied to certain medical technologies. Such an exemption would permit tariff-free flows of laptops that meet defined classroom specifications and undergo verifiable audits of their bill of materials. Second, member economies should pilot an APEC Trusted EdTech Corridor, pooling forecast demand and awarding multi-year contracts to diversified assembly plants in at least three jurisdictions, thereby reducing single-country exposure without erecting price-inflating walls. Third, export‑control authorities must adopt a dynamic risk registry that sunsets restrictions absent evidence of continuing vulnerability, thereby preventing yesterday's threats from becoming today's rent‑seeking instruments. Finally, the World Bank's June 2025 Global Economic Prospects calls for "strengthened global cooperation to tackle trade fragmentation." APEC can operationalize this mandate by linking its longstanding free-trade roadmap to measurable learning-outcome benchmarks, ensuring that security policies are evaluated not only for their strategic effect but also for their educational collateral.

Hard Questions, Evidence‑Based Answers

Critics contend that any carve‑out invites loopholes: hostile actors could smuggle sensitive chips inside "classroom" laptops. The rebuttal lies in tamper-proof supply-chain transparency—QR-coded bills of materials and randomly sampled teardown audits, financed through a modest APEC trust fund. Others argue that targeted tariffs spur local manufacture. Yet, the Trafera and NCES data suggest that rising costs have so far translated into delays rather than reshoring, with U.S. assembly still reliant on imported sub-components. A further critique indicates that security concerns should take precedence over economic efficiency. True, but security includes educational resilience: a nation that cannot equip its classrooms cannot innovate its way out of dependency. Finally, skeptics warn that flexible export‑control regimes could undermine alliance solidarity. Korea's experience shows the opposite: rigid rules pushed a close ally into revenue losses and strategic uncertainty. A smarter, data-driven regime would deepen—not dilute—trust by aligning measures with shared developmental goals.

Reclaiming Free Trade for a Secure, Educated Pacific

Tariffs that raise Chromebook prices higher than chemistry textbooks capture only the surface of a deeper fracture: an Asia‑Pacific trade system that once powered unprecedented prosperity now strains under the weight of security‑first reflexes. We have argued that economic security and free trade are not mutually exclusive if policymakers adopt a security‑conditioned compact anchored in transparent risk assessment and protected corridors for education‑critical goods. The numbers tell a cautionary tale—0.4% export growth, 32 million lost learning hours, billions in delayed device roll‑outs—but they also illuminate a path forward. By carving out verifiable low-risk categories, diversifying supply chains without incurring punitive costs, and aligning export controls with measurable learning outcomes, APEC can uphold its founding free-trade creed while fortifying itself against predatory coercion. The choice is stark: double down on blunt instruments that fragment markets and classrooms alike, or embrace disciplined interdependence that keeps both citizens and circuits secure. Legislators, administrators, and educators must press for the latter, because every levied percentage point that prices a laptop out of reach is a percentage point shaved off the region's collective future.

The original article was authored by Toshiya Takahashi, Professor of International Relations at Shoin University in Japan. The English version, titled "APEC watches as economic security reshapes trade," was published by East Asia Forum.

References

APEC Policy Support Unit. (2025, March). APEC Regional Trends Analysis

APEC Secretariat. (2025, May 15). Press release: APEC forecasts 2.6 percent growth and urges action on trade barriers

Consumer Technology Association & Trade Partnership Worldwide. (2024, October). Sticker Shock Incoming: Tariffs and 2025 device pricing

KDI Journal of Economic Policy. (2024). The impact of U.S. export controls on Korean semiconductor exports

National Center for Education Statistics. (2024, January 18). School Pulse Panel: Procurement challenges data release

Reuters. (2025, May 15). APEC warns of stalling trade due to tariffs

Reuters. (2025, July 18). Philippines seeks trade‑security balance in Washington talks

UNESCO. (2023). Technology in Education: Global connectivity gaps

Washington Post. (2025, May 30). Schools blame tariffs for rising costs and supply woes

World Bank. (2025, June). Global Economic Prospects, Chapter 1

World Bank. (2025, June). Global Economic Prospects, Chapter 2 (East Asia and Pacific)

Comment