Tariffs, Tech Dreams, and the Mirage of a US–Japan Sovereign Wealth Fund

Input

Changed

This article was independently developed by The Economy editorial team and draws on original analysis published by East Asia Forum. The content has been substantially rewritten, expanded, and reframed for broader context and relevance. All views expressed are solely those of the author and do not represent the official position of East Asia Forum or its contributors.

More than US$700 billion in private investment pledges, a newly announced 25% tariff wall, and a joint fund whose promoters claim it will "future‑proof" the American alliance with Japan: that volatile mix now defines Washington's economic conversation. Since January, SoftBank founder Masayoshi Son has touted an eye‑popping US$500 billion "Stargate" data‑centre build‑out—upped to US$700 billion in May—while simultaneously pitching a US–Japan sovereign wealth fund (SWF) to backstop the venture. However, this proposal, which risks amplifying the very distortions that SWFs were designed to tame, is not without its potential risks. President Donald Trump has frozen tariffs on Japanese exports at a punitive 25%, signaling that concessions might come only if Tokyo underwrites the fund. Add Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent's admission that the scheme is on hold amid legal doubts, and the picture that emerges is not visionary statecraft but brass‑knuckle leverage: a private financier short on cash and a White House keen to recycle tariff revenue into an election‑season industrial trophy.

A Private Gambit Dressed as Public Statecraft

Son's pitch is seductive for politicians: marry Japanese capital with US strategic ambitions, neutralise tariff tensions, and generate headlines about "ally‑powered AI." Yet every structural feature of the idea reeks of self‑interest. SoftBank lacks the dry powder to shoulder Stargate's massive outlays; Vision Fund 2 is still nursing multi‑billion‑dollar paper losses and co‑investor fatigue. A government-branded pool would therefore socialize early-stage risk while preserving upside for the initiators. Trump's enthusiasm dovetails neatly with that calculus. By framing the SWF as an instrument of national competitiveness, he can deflect criticism that the tariff regime hurts both US consumers and Japanese partners, while simultaneously directing capital toward projects that align with his political narrative. The East Asia Forum's recent critique highlights a caution: American capital markets are already the deepest in the world; a state-directed vehicle only duplicates private capacity and invites mercantilist carve-outs. Bessent's decision to shelve the plan—for now—confirms that even a loyal cabinet can recognise a bridge too far.

How Sovereign Wealth Funds Work—And Why This Model Misfires

Classic SWFs arise from windfall surpluses in resource‑rich or trade‑surplus nations. Norway's oil fund, Abu Dhabi's ADIA, and Singapore's GIC convert finite revenues into intergenerational savings and stabilization cushions. Their mandates are narrowly financial, their governance increasingly insulated from day‑to‑day politics, and their jurisdictions—often small, open economies—cannot rely on deep private capital markets. By contrast, the United States runs a budget deficit of nearly 7% of GDP, faces net external liabilities, and commands Wall Street's boundless liquidity. As the OMFIF analysis notes, funding an American SWF would require asset sales, fresh borrowing, or hypothecated tariff revenue—none of which fits the Santiago Principles that guide best practice. Globally, SWFs already manage US$13–14 trillion, yet more than half of that pool belongs to fewer than fifteen countries; size does not guarantee discipline. In economies where political cycles are short and lobbying firepower is vast, sovereign vehicles metastasise into slush funds. Layering Japanese participation onto that framework adds new veto points without supplying the stabilising excess savings that justify a fund in the first place. Methodologically, the figures cited here draw on GlobalSWF's 2025 scorecard of 200 funds and the Invesco survey of state investors managing US$27 trillion; both sources convert local-currency disclosures to US dollars using the IMF's reference rates as of March 2025.

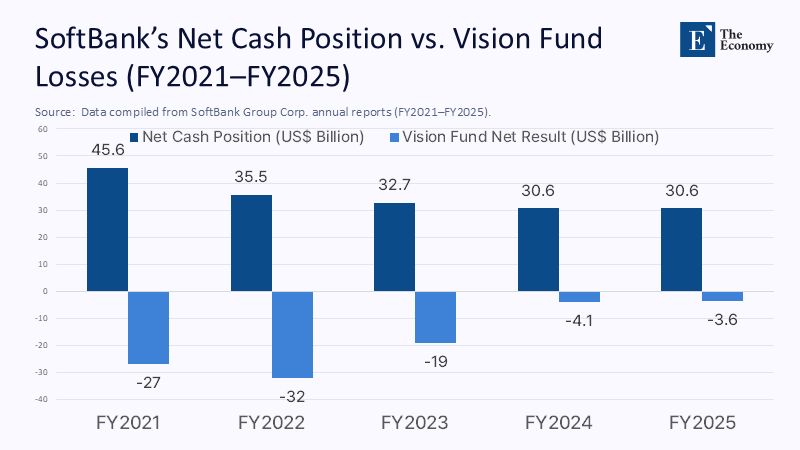

SoftBank's Balance‑Sheet Reality and the Quest for Cash

Strip away the diplomatic gloss, and a simpler story appears: SoftBank needs liquidity. The Vision funds have oscillated between record losses and one-off gains; net cash on hand fell from US$45.6 billion to US$30.6 billion within nine months, even after asset sales. Despite eking out its first annual profit in four years—¥1.15 trillion in FY 2025—SoftBank still logged a ¥526 billion loss in Vision Fund 2, while pledging up to US$40 billion more to OpenAI. The simultaneous promise to syndicate US$10 billion and inject another US$700 billion into US AI infrastructure underscores the mismatch between ambition and available capital. The SWF addresses that mismatch by converting diplomatic goodwill into financing: Japanese officials hope that tariff relief will follow once the cash is committed; the White House hopes construction will start before the election; and Son hopes that governments will validate valuations that private markets are increasingly questioning. In short, the fund would externalize investment risk precisely at the moment SoftBank confronts portfolio markdowns and a higher-rate environment.

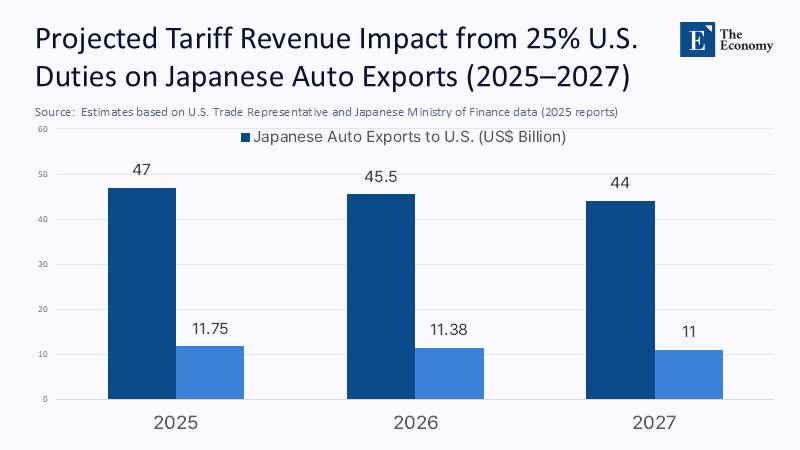

Tariff Leverage and Political Self‑Dealing

Tariffs are no longer merely trade tools; they are bargaining chips for capital placement. Trump's July pledge to "live by the letter" of 25% duties on Japanese imports unless "constructive investments" emerge places Tokyo in an impossible bind: accept a politicized fund or endure escalating levies that imperil an auto sector representing 28 % of Japan's US exports. The White House's tariff tracker projects a baseline reciprocal tariff of 15–20% for dozens of countries absent new deals, creating an auction where access to US markets is exchanged for participation in administration‑favoured ventures. Bessent's pause does not change the underlying dynamic; it merely postpones the day when Congress asks why tariff revenue is being earmarked for speculative equity stakes rather than deficit reduction. Historically, tariff hypothecation has produced muddled incentives and legal challenges. Here, it threatens to hand the executive branch a discretionary capital pool with limited congressional oversight—precisely the scenario critics of industrial policy warned about in the CHIPS Act debates, now amplified by a foreign-policy twist and the potential misuse of funds.

Governance Risks and East‑Asian Lessons in State Capitalism

Proponents argue that Japan's experience with the Government Pension Investment Fund (GPIF) and Korea's Investment Corporation proves that large democracies can run disciplined state investors. Yet both cases demonstrate how easily political objectives infiltrate portfolio choices: GPIF's 2024 shift toward strategic domestic ETFs followed cabinet pressure to boost the stock market, while Seoul's push for a "Korea Discount" law reoriented KIC toward national champion bailouts. Those moves pale beside the Trump administration's willingness to demand a golden share in Nippon Steel's acquisition of US Steel—evidence that Washington, too, can blur commercial and political lines. An allied, bi‑jurisdictional fund would multiply such temptations. OMFIF warns that without explicit legal firewalls and transparent objectives, any US SWF risks devolving into a lever for foreign‑policy signaling or domestic patronage. The United States prides itself on open capital allocation; importing a Japanese-style government fund, seeded by tariff pain and steered by a single corporate sponsor, would graft East Asian political capitalism onto the American fiscal body with none of the stabilizing surpluses that support it abroad.

A Better Way Forward Than a Bilateral Slush Fund

If the strategic goal is resilient high-tech supply chains and deeper alliance integration, better instruments already exist: targeted export-credit facilities, plurilateral investment-screening coordination, and mutual recognition of security standards for critical nodes, such as data centers and chip fabs. These tools address genuine public-good gaps—insurance against coercive blockades and a shared vetting capacity—without concentrating hundreds of billions of dollars under executive-branch discretion.

They also avoid entrenching tariff brinkmanship as the price of cooperation. Washington and Tokyo can still leverage private capital by clarifying permitting timelines, harmonising subsidy regimes, and expanding tax credits for joint R&D, all steps compatible with open‑market norms. Crucially, those reforms do not require masking a private fund‑raising challenge behind sovereign branding. Saying no to the SWF is not anti‑alliance; it is pro‑credibility. Legislators should demand a sunset of the 25% tariff once genuine regulatory cooperation milestones are met, and reserve sovereign balance-sheet risk for events, such as pandemic relief or energy shocks, that markets cannot finance on their own.

End the Charade, Fix the Fundamentals

The SoftBank–Trump sovereign wealth plan purports to fuse private dynamism with public purpose. Still, its arithmetic and incentives reveal a more prosaic reality: a cash-hungry conglomerate courting a tariff-wielding administration that relishes splashy announcements.

America does not lack capital, and Japan does not lack vehicles for strategic investment; what both risk lacking is the policy discipline to separate alliance stewardship from corporate rescue. Abandoning the SWF gambit would send a clearer signal of market fidelity than any communiqué. It would also free negotiators to address the real sources of friction—tariff escalation and supply‑chain opacity—without mortgaging billions to a fund designed in haste and destined for political interference. The next time policymakers invoke sovereign wealth, they should recall that actual wealth funds arise from surplus, not shortage, and restraint, not expediency. On those criteria, the US–Japan proposal fails its due diligence test.

The original article was authored by Adam Dixon, an American professor based in Edinburgh, Scotland. The English version, titled "A US–Japan sovereign wealth fund is a bad idea," was published by East Asia Forum.

References

Das, U., & Sobel, M. (2025, February 7). US sovereign wealth fund debate: A solution in search of a problem? OMFIF.

Dixon, A. (2025, July 15). A US–Japan sovereign wealth fund is a bad idea. East Asia Forum.

Global SWF. (2025, July). 2025 GSR Scoreboard.

Hunnicutt, T., & Shalal, A. (2025, July 16). Trump says US will stick to 25% tariff on Japan. Reuters.

Invesco. (2025, July 13). Sovereign Investor Survey 2025 [Reuters summary].

Kelley, A. (2025, May 1). Companies announce billions in investments to support emerging tech. NextGov.

Reuters. (2025, May 13). Japan's SoftBank Group books first annual profit in four years.

Reuters. (2025, February 12). SoftBank's Son to return to form with big bets and quarterly loss.

Roic AI News. (2025, May 23). Bessent: Sovereign wealth fund on pause until administration handles other priorities.

Trade Compliance Resource Hub. (2025, July 17). Trump 2.0 Tariff Tracker.

Comment