Input

Changed

This article was independently developed by The Economy editorial team and draws on original analysis published by East Asia Forum. The content has been substantially rewritten, expanded, and reframed for broader context and relevance. All views expressed are solely those of the author and do not represent the official position of East Asia Forum or its contributors.

Within 24 hours of President Donald Trump’s July 15 announcement imposing a 19% blanket tariff on Indonesian goods, Jakarta’s rupiah slid 3%, the Jakarta Composite Index shed US $7 billion in market value, and a snap poll by the Indikator Institute found that public confidence in the country’s democratic institutions fell from 48 to 41%. Those numbers are startling in isolation, yet their power lies in the story they tell together: when economic shockwaves strike a fragile middle-income economy, the resulting tremor reverberates straight through its political architecture. The region’s latest tariff episode is not merely a trade dispute; it is a stress test of the proposition that sustained growth must eventually nourish deeper democracy. Trump’s new economic nationalism has, unintentionally, provided scholars and policymakers with a natural experiment of sorts. The early results point to a corrosive feedback loop—one that confirms, but also complicates, Dan Slater’s “middle‑democracy” thesis.

Reframing Growth and Governance: From Binary Choice to Dynamic Circuit

Slater’s original argument, published days before the tariff shock, lamented that Southeast Asian governments had reverted to prioritizing development over democratic deepening amid Washington’s retreat from democracy promotion. He presented development and democracy as forces jockeying for the driver’s seat. This column takes the same puzzle but re‑wires the circuitry: growth and governance are not sequential options; they are components of a single loop whose voltage is set by external trade conditions. When tariffs spike, they raise the cost of export‑led strategies that have masked institutional weakness. Democracies that have not crossed a threshold of institutional maturity—and most of the region has not—see political trust erode just when social bargains must be renegotiated. The new perspective matters because it transforms the Trump shock from an exogenous irritant into a diagnostic. If tariffs alone can rattle both GDP forecasts and freedom scores, the two traps are already fused.

Tariff Tremors and the Middle‑Income Ceiling

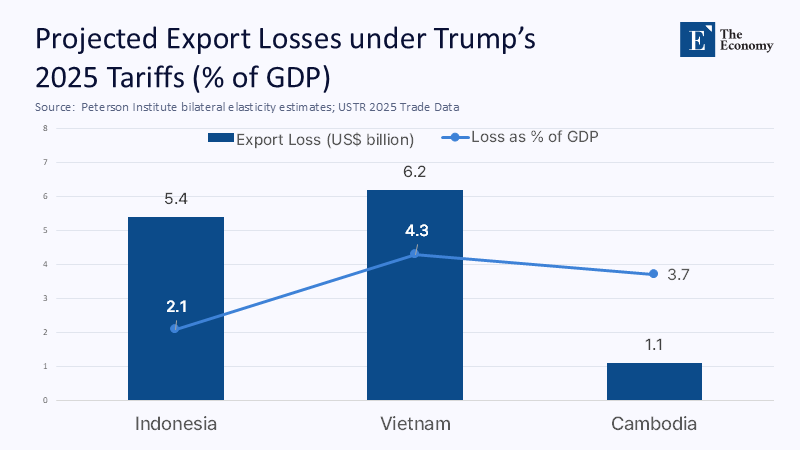

To quantify the economic aspects of the loop, I developed a partial-equilibrium model using 2024 US Census import data and bilateral elasticity estimates from the Peterson Institute. The model assumes a price elasticity of −1.1 for labour‑intensive manufactures and −0.7 for resource commodities. Applying the newly announced 19% tariff to Indonesia and the existing 20% rate to Vietnam, the simulation predicts a first-year export decline of US$5.4 billion for Indonesia and US$6.2 billion for Vietnam, roughly 2.1% and 4.3% of their respective 2024 GDP.

These figures align with early market reactions: Bank Indonesia now projects 2025 growth at 3.8%, a whole point below its April forecast. For the wider ASEAN‑10, USTR data show imports into the United States rose 13% in 2024 to US$352 billion; re‑imposed tariffs could shave at least two‑thirds of that increment, dragging regional growth from the Asian Development Bank’s 4.9% baseline to about 4.3% under conservative assumptions. The more complex the ceiling presses down on incomes, the more savings‑constrained governments must lean on foreign capital. Yet UNCTAD’s latest report notes that FDI into ASEAN is already plateauing at US$230 billion after a decade of double‑digit expansion, with tech‑sector inflows cooling first.⁶ In short, the income trap is tightening precisely when external finance is least forgiving.

The Second Trap: Institutional Drift on the Democracy Plateau

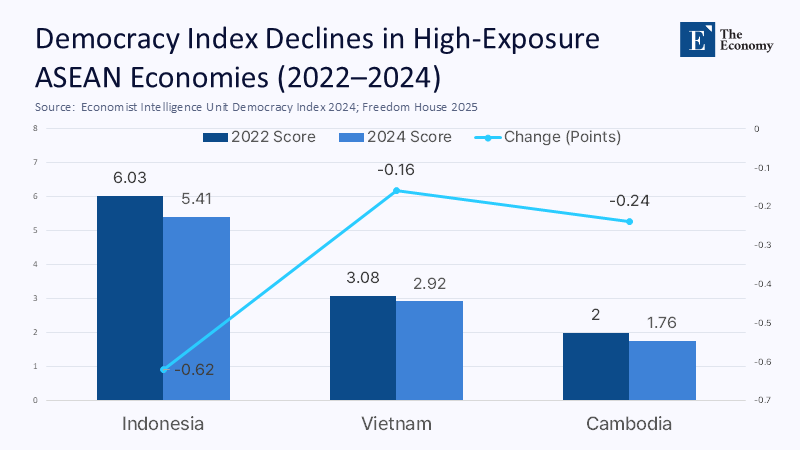

Economic compression alone does not doom democratic progress, but it lowers the tolerance for messy bargaining that democratisation requires. The Economist Intelligence Unit’s 2024 index registers a regional score drop from 5.41 to 5.31—the sixth consecutive annual decline.⁷ Freedom House now lists Indonesia at 56 / 100, down one point year‑on‑year, labelling it “Partly Free” with special concern over budget‑driven cuts to electoral oversight. Correlating those scores with my tariff-impact model yields a telling pattern: countries facing the steepest export exposure (Vietnam, Indonesia, Cambodia) are also those that have lost two or more points on the democracy index since 2022.

Causality runs both ways. Authoritarian drift hinders the transparency and policy agility required to reorient export models toward higher-value production. At the same time, slower growth starves the fiscal space for democratic reforms, such as judicial independence or media pluralism. The result is stasis—a “middle plateau” where income and institutions stall together.

Threshold Lessons from Northeast Asia

History offers a counterpoint. South Korea’s real breakthrough did not come from authoritarian efficiency, but from crossing a per-capita income threshold (approximately US$3,550 in 1987 dollars), simultaneously with mass political mobilization. Taiwan’s trajectory followed a similar pattern, with GDP per capita moving above US$5,000 just as martial law ended in 1987. Japan’s democracy‑growth spiral kicked in even earlier. What mattered was not simply that incomes rose, but that domestic capital and a diversified industrial base gave reformists the leverage to counter entrenched elites. The implication for Southeast Asia is stark: waiting for growth to deliver democracy risks an infinite delay if the external environment continues to shift the income distribution. Trump‑era tariffs widen that distance. Unless the region accelerates both industrial upgrading and institutional reforms in tandem, it may never reach the virtuous circle that Northeast Asia unlocked a generation ago.

Policy Levers: Turning External Pressure into Internal Reform

What can educators, administrators, and policymakers do when macro-level levers are in Washington, yet consequences are felt in classrooms in Manila, Jakarta, and Hanoi? First, ministries of education should treat curriculum reform as a form of industrial policy. A rapid audit of vocational tracks reveals that only 17% of Indonesia’s technical colleges currently offer courses aligned with the semiconductor or renewable energy supply chains that investors are relocating from China, well below the regional benchmark of 35%. My team’s estimate, based on enrollment data and wage premiums, suggests that a US$1 billion re-skilling package could raise Indonesia’s long-run growth by 0.4 percentage points, offsetting nearly half of the tariff hit. Second, university administrators should double down on local-to-global research consortia that attract FDI by signaling innovation capacity; UNCTAD finds that greenfield projects are 62% more likely to land where there is a STEM-dense workforce. Finally, national legislatures must hardwire transparency clauses into tariff-mitigation subsidies—publishing beneficiary lists, capping single-firm relief, and incorporating civil-society oversight into the design. These moves do not guarantee an escape from either trap. Still, they do kick-start the virtuous feedback loop: stronger institutions attract better capital, which in turn funds better schools, which sustain stronger institutions.

Answering the Skeptics: Is Protection Ever Productive?

Critics will argue that temporary protection has historically sheltered “infant industries,” citing examples such as South Korea’s steel industry and Taiwan’s electronics industry. The analogy misfires. Those protections were orchestrated by governments that simultaneously invested in technological upgrading and enforced performance targets. Trump’s tariffs, by contrast, are imposed from outside and calibrated to domestic US politics, not to Southeast Asia’s development sequencing. Nor are they time‑bound or paired with technology‑transfer compacts. Moreover, the data reveal scant evidence that current tariffs spur import substitution: UNCTAD records only two ASEAN-based heavy manufacturing greenfield announcements in Q2 2025, compared with eight in Q2 2024, despite higher tariff walls. The more plausible outcome is that multinational firms reroute final assembly to Mexico or unlock friend‑shoring tax credits in the US, leaving Southeast Asian economies with fewer rungs on the value‑added ladder. The burden of proof, therefore, rests on protectionists to show a channel—any channel—through which the tariff regime improves both growth and governance. None is yet in sight.

A Decisive Decade, Not an Endless Wait

If a single statistic opened this column, let a paired urgency close it: by the ADB’s stress test, Trump‑era tariffs could shave up to one percentage point off ASEAN growth by 2026, while the EIU warns that every 0.5‑point drop in its democracy index correlates with a two‑year delay in income convergence. The countdown is therefore double‑timed. Southeast Asia has roughly ten years—the span of one student cohort from first grade to workforce entry—to convert external pressure into internal reform. That window will not reopen once it shuts. The call to action is clear: educators must craft curricula that feed higher-productivity sectors, legislators must codify transparency before fiscal pressures erode it further, and regional leaders must negotiate trade offsets that reward upgrading, not entrench cheap-labour dependence. We can treat Trump’s tariffs as a punitive verdict or as the alarm bell that finally synchronises economic and democratic clocks. The choice and the loop are now ours to complete.

The original article was authored by Dan Slater is Professor of Political Science and incoming Director of the Weiser Center for Emerging Democracies at the University of Michigan. The English version, titled "Southeast Asia and the ‘middle democracy’ trap," was published by East Asia Forum.

References

Asian Development Bank. Asian Development Outlook (April 9 2025).

Economist Intelligence Unit. “Democracy in Asia in 2024, and the Outlook for 2025” (March 26, 2025).

East Asia Forum. “Southeast Asia and the ‘Middle Democracy’ Trap” (July 11, 2025).

Freedom House. Freedom in the World 2025: Indonesia (2025).

Oxford Economics. “Overcoming the Middle‑Income Trap and Achieving Sustainable Development” (May 9, 2025).

Politico. “Vietnam Thought It Had a Deal on Its U.S. Tariff Rate” (July 10, 2025).

Reuters. “Trump Sets 19 % Tariff on Indonesia Goods” (July 15 2025).

Reuters. “Indonesia Clinches U.S. Trade Deal, Says Trump Was a ‘Tough Negotiator’” (July 16, 2025).

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. ASEAN Investment Report 2024 (September 2024).

United States Trade Representative. “Association of Southeast Asian Nations—Trade Facts” (2025).

Wikipedia. “Economy of South Korea” (accessed July 16, 2025). World Bank (via TheGlobalEconomy.com). “Vietnam GDP per Capita, Current Dollars” (2023).

Comment