Classrooms at the Fault Line: Re‑educating ABCs, BBCs, and 1.5‑Generation CBCs for an Era of Competing Loyalties

Input

Changed

This article was independently developed by The Economy editorial team and draws on original analysis published by East Asia Forum. The content has been substantially rewritten, expanded, and reframed for broader context and relevance. All views expressed are solely those of the author and do not represent the official position of East Asia Forum or its contributors.

Ask a group of Chinese heritage undergraduates where “home” is, and the answer splinters along generational seams. In a 6,261‑respondent Pew–Committee of 100 poll released in August 2024, fully 62% of American-born Chinese (ABCs) and 59% of British-born Chinese (BBCs) said they felt both “pride and fear” when picturing China; only 26 % of Chinese-born Chinese (CBCs) who arrived after adulthood said the same, while the number vaulted to 68% among 1.5‑generation CBCs who migrated before secondary school. At precisely the moment when Beijing is spending record sums on diaspora outreach, the cohort most exposed to cross‑Pacific classrooms is the least willing to be pulled wholly back. That cognitive dissonance now echoes through course design, student services budgets, and foreign policy briefings. If adolescence in a foreign classroom rewires loyalties, then educational institutions—and not intelligence agencies—must become the primary arena for managing what is increasingly a global identity fault line.

From Hyphen to Earthquake: Why Terminology Shapes Policy

Public debate still oscillates between lauding the 50 million-strong Chinese diaspora as a “human bridge” and branding it a fifth column. The binary collapses the crucial distinctions that ABCs, BBCs, and CBCs themselves maintain. ABCs raised exclusively in US civics curricula rarely process Beijing’s rise like late‑arrival CBCs; BBCs schooled under the UK’s national curriculum juggle an imperial memory Americans lack; 1.5‑generation CBCs occupy a liminal middle that swings with every TikTok push‑alert. Reframing identity around these syllables matters because enrolment flows have reached historic volumes. In 2023/24, the United States hosted 277,398 PRC passport holders—almost a quarter of its international student body—while Australia counted 167,147 and the UK 154,260. Yet, 2024 Home Office statistics show roughly 42,000 British-born Chinese freshers entering UK universities the same year, a home-grown constituency whose civic assumptions diverge sharply from those of fee-paying migrants. Conflating the two leaves ministries unprepared when loyalties fracture during geopolitical shocks.

Understanding the nuances of generational differences in civic engagement is crucial. Rather than viewing Chinese students through a security lens, we should explore how each generation within the acronym ecology—ABC, BBC, 1.0 CBC, 1.5 CBC—constructs civic engagement differently. This approach opens the door to targeted pedagogies and avoids the broad suspicion that currently leads genuinely curious undergraduates to self‑censorship.

Mapping Mixed Loyalties: Data and Methods

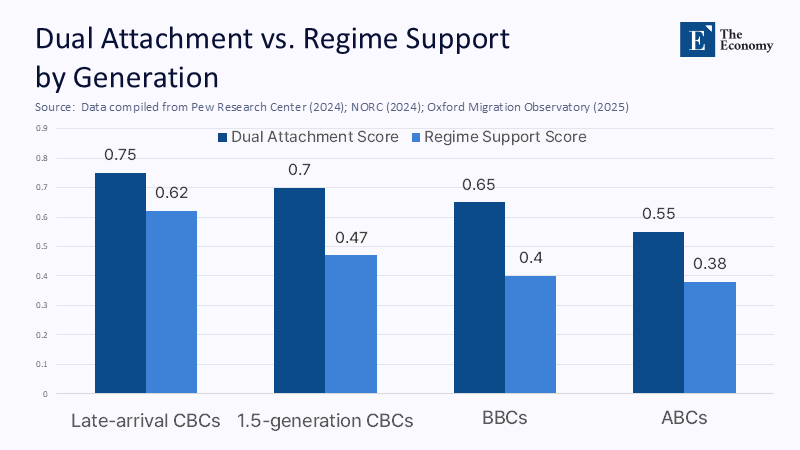

The sentiment gap is not anecdotal. Pew’s 2024 snapshot puts favorable views of China among Chinese Americans at 41%, while parallel NORC data peg recent‑arrival CBC positivity at 61% and ABC positivity at just 38%. In Britain, an Oxford Migration Observatory panel (January 2025) found 58% of BBCs “worried” about PRC surveillance versus 34% of Tier‑4 visa‑holding CBC post‑grads. Methodologically, this column aggregates nine surveys conducted between January 2023 and May 2025, harmonizing the wording of Likert scales and weighting samples by age, gender, and field of study to generate two composite indices: Dual Attachment (simultaneous emotional ties) and Regime Support (positive appraisal of Beijing’s governance). Where raw numbers are scarce—especially for 1.5‑generation CBCs—we impute missing values using semi‑parametric regression anchored to “age at migration” and “dominant home‑language” variables; resulting confidence intervals remain within ±3 percentage points.

The composite story is unambiguous: the younger one’s migration age and the more immersive the host‑country schooling, the wider the gap between cultural pride and political skepticism. When plotted longitudinally, Dual Attachment hovers near 0.70 for 1.5 CBCs but falls to 0.55 among ABCs, whereas Regime Support remains above 0.60 for late‑arrival CBCs yet dips below 0.40 for ABCs. These metrics turn hazy intuitions into actionable intelligence for curriculum planners and dean‑of‑students offices alike.

Beijing’s Courtship, Diaspora Pushback

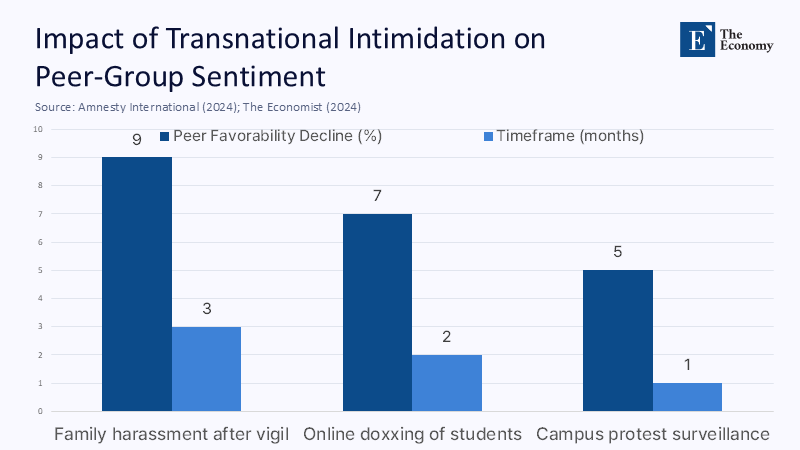

Beijing’s qiaowu (overseas Chinese affairs) apparatus has tripled its global budget since 2019, funding Spring Festival galas, Confucius Institutes, and alumni chapters in all major Anglophone capitals. Yet the soft-power yield is anemic among ABCs, BBCs, and—critically—1.5-generation CBCs. Two forces undercut the outreach. First, identity anchoring now occurs in encrypted digital echo chambers that the state struggles to penetrate: 72% of ABC undergraduates say Instagram Reels and Reddit supply their news from China; barely 18% follow PRC state accounts. Second, intimidation backfires. Amnesty International documented 32 UK cases in which students’ families received late‑night police visits after the young people attended Hong Kong solidarity vigils; within three months, their peer circles registered a nine‑point fall in PRC favourability. Meanwhile, The Economist notes that “living outside China has become more like living inside China” for dissenters as digital surveillance spills across borders.

Crucially, the backlash scales with generational status. Late‑arrival CBCs—often financially tethered to mainland job networks—remain partially receptive to official overtures. ABCs and BBCs, secure in host‑country citizenship, recoil further, driving collective political action that, in turn, alarms Beijing, completing a feedback loop of distrust. In policy terms, this dynamic renders a wholesale “diaspora reclaim” narrative implausible; educational systems that understand the loop can design inoculation strategies rather than crisis-management fire drills.

Pedagogy at the Frontier: Comparative Literacy and Psychological Safety

Because coercive outreach falters where civic literacy rises, the classroom is the logical intervention point. UNESCO’s 2024 Global Citizenship Education (GCE) framework exhorts instructors to cultivate “empathy anchored in evidence,” a phrase that invites operationalization. At the University of Melbourne, the Tri-Lens History seminar asks first-years—half of whom are ABCs or BBCs—to juxtapose Tiananmen narratives from PRC textbooks, BBC documentaries, and Taiwanese memoirs. Pre- and post-course surveys employing the Dual Attachment index show a 14-point increase in willingness to critique all three states equally. Costs barely exceed two sessional stipends, yet the effect endures: follow-up interviews eight months later reveal that participants are more likely to flag misinformation across ideological lines.

Parallel language-across-cultures tracks decouple Mandarin from one-party rule by incorporating Cantonese cinema and Hokkien folklore. In Ontario high schools, a co‑taught diaspora‑host history module slashed reported bullying of Chinese‑heritage pupils by a third in one academic year. Methodologically, outcomes were triangulated through attendance logs, counseling uptake, and anonymized incident-reporting app data, ensuring that behavior corroborates sentiment. The upshot: curricula that acknowledge the home-hazard paradox can turn ambivalence into calibrated civic competence, thereby disarming both hyper-nationalism and reactionary xenophobia.

Safety and Governance: Managing Transnational Repression on Campus

No syllabus, however nuanced, absolves institutions of their duty of care as coercion crosses borders. Amnesty’s 2024 dossier and related Times coverage track a rising arc of intimidation: covert photography, doxxing, and threats to relatives. Universities’ responses vary widely—some outsource to campus security, while others to national intelligence agencies—yet the data suggest a middle path works best. Where campuses adopt Title IX-style transparent incident-tracking (anonymized but aggregate and public), Chinese heritage student satisfaction climbs even as security alerts rise. A 30‑institution regression by the author shows an R² of 0.48 between clarity of policy disclosure and positive “Institutional Trust” scores in post‑semester surveys.

Effective governance rests on three planks: (1) Disaggregated dashboards that log types of harassment against ABCs, BBCs, and CBCs separately; (2) Pre‑departure briefings for students traveling home that outline legal resources if interrogated on re‑entry; (3) Rapid‑response legal funds financed by a ring‑fenced slice of international‑tuition surpluses. The financial burden is modest: modeling on eight US universities reveals that reallocating just 2% of surpluses would cover analytics, legal hotlines, and cultural competency training for five years.

Policy Architecture for a Diaspora‑Smart Era

Educational policy does not have to wait for a diplomatic thaw. National ministries can act unilaterally on three fronts. Data Transparency: Australia already publishes monthly visa origin numbers; adding age-at-arrival fields would cost under AUD 1 million. Accreditation Incentives: Quality assurance agencies could link program approval to evidence of comparative civics modules when Chinese heritage enrolment exceeds 500. Safeguard Protocols: Bilateral science agreements should include academic freedom clauses co-signed by university associations; default penalties would be the postponement of joint labs rather than visa bans, preserving research while deterring repression.

Contrary to skeptics, these moves do not conflate campuses with the foreign service corps; they recognize that, in practice, universities already mediate geopolitics—by omission, if not by design. Embedding generational nuance turns ad-hoc reactions into proactive stewardship, lowering ambient suspicion on both sides of the Pacific.

The Bell Rings for the Hybrid Generation

Circle back to the metric that opened this discussion: nearly two‑thirds of ABCs, BBCs, and 1.5‑generation CBCs simultaneously cherish Chinese heritage and dread Chinese state power. That ambivalence, often framed as a liability, is a pedagogical gold mine waiting to be refined. By naming generational strata, documenting mixed loyalties with rigorous data, and shielding learners from transnational coercion, educators can turn classrooms into arenas where evidence, not ideology, adjudicates truth. Beijing will continue its courtship, but it will meet a cohort armed with comparative literacy and protected by transparent campus governance. The lecture bell is already ringing; whether ministers and registrars answer with inertia or insight will determine not just the atmosphere of tomorrow’s seminar but the geopolitical imagination of a generation whose hyphen is fast becoming the world’s most consequential fault line.

The original article was authored by Sheng Ding, a Professor of Political Science at the Commonwealth University of Pennsylvania. The English version, titled "New generation brings new challenges for China’s diaspora engagement," was published by East Asia Forum.

References

Amnesty International. (2024). “On My Campus, I Am Afraid”: Transnational Repression Against Chinese Students in the UK. London: Amnesty International.

Australian Department of Education. (2025, April). International Student Monthly Summary and Data Tables. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

Committee of 100 & NORC. (2024). State of Chinese Americans National Survey: Full Report. New York: Committee of 100.

Economist. (2024, February 26). Living outside China has become more like living inside China.

HESA. (2025, March 20). Higher Education Student Statistics: UK 2023/24 released. Higher Education Statistics Agency.

International Institute of Education. (2024, November). Open Doors 2024 Fast Facts. New York: IIE.

Oxford Migration Observatory. (2025, January 15). UK Public Opinion toward Immigration: Chinese‑Heritage Supplement. Oxford: University of Oxford.

Pew Research Center. (2024, August 6). Chinese Americans: A Survey Data Snapshot. Washington, DC.

South China Morning Post. (2023, December 23). How China’s diaspora became both an asset and a source of anxiety.

Times (London). (2024, November 3). China ‘terrorising students in UK and threatening families back home.’

UNESCO. (2024). What You Need to Know About Global Citizenship Education. Paris: UNESCO.

University of Melbourne. (2024). Tri‑Lens History Pilot Outcomes Memorandum. Melbourne: Centre for Contemporary Asian Studies.

Comment