Input

Changed

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

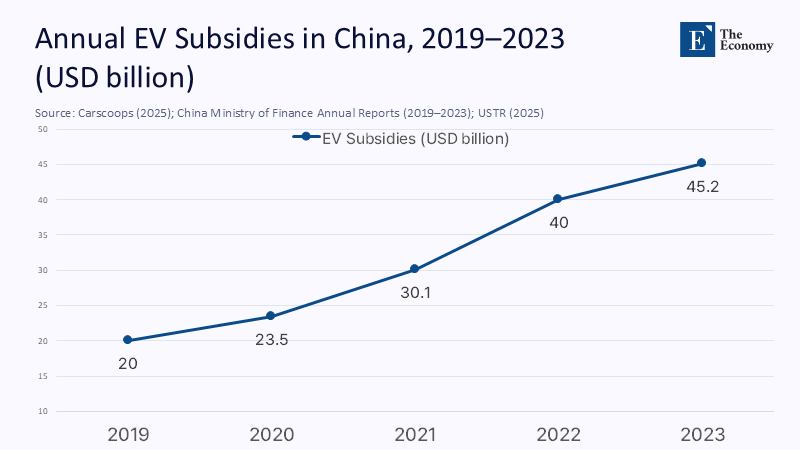

As of last year, a staggering 84% of the assets held by Chinese firms in the Fortune Global 500—companies that cater to global markets—were ultimately controlled, directly or indirectly, by the Chinese party‑state. Simultaneously, Beijing injected an estimated US$45 billion in fresh subsidies into its electric‑vehicle champions, a single‑year outlay that, after purchasing‑power adjustments, almost matches the entire five‑year subsidy envelope of the US CHIPS and Science Act. These numbers reveal a truth we can no longer ignore: China’s competitive edge is not the result of free markets, but of a complex public-private network where every “private” firm is potentially a node in national industrial strategy. If we persist in viewing tariffs as a country-level tool while overlooking the underlying network, we risk misguiding our students and misdirecting our policy.

Reframing the Debate: From National Flags to Ownership Networks

The CEPR/VoxEU column “Beyond Tariffs” is a significant piece that rightly urged Washington to move from blanket pressure on China toward targeted scrutiny of state‑owned enterprises (SOEs). This shift is crucial because Beijing’s industrial machine no longer rests on classic SOEs alone; it relies on concentric rings of minority stakes, golden shares, and procurement mandates woven through firms that advertise themselves as private. Big-data ownership maps produced since 2024 reveal that what appears to be a market is, in fact, a mesh.

That wider lens matters because it captures the levers—state venture funds, municipal land grants, tax deferrals, export credits—that turn political directives into firm‑level cost advantages. The March 2024 CSIS study that parsed 40 million registrations found 78% of China’s top 1,000 “private” owners directly tied to the state, while 3.6 million firms sit within three degrees of a state shareholder. By assets, 84% of Chinese Fortune 500 entities are state-controlled, a dominance invisible to tariff schedules but decisive on the ground.

Mapping the Subsidy Web: Methods and Evidence

Quantifying the lattice is messy, yet fragments converge once open‑source disclosures, bond prospectuses, provincial budgets, and customs data are triangulated. Between 2009 and 2023, Beijing invested at least US$230 billion in the EV ecosystem—US$45.2 billion in 2023 alone—through buyer rebates, VAT exemptions, upstream battery grants, and land leases. Huawei, portrayed abroad as an employee-owned innovator, received more than US$1 billion in direct government grants in 2023, quadrupling its 2019 haul, while local governments injected land and cash to keep its chip arm afloat. Parallel flows run through critical-mineral exploration, where provinces now devote ¥100 billion a year to subsidies and more straightforward land conversion.

Where complex numbers are not applicable, we rely on conservative proxies. A July 2025 audit showed ¥143 million paid to BYD for just 4,900 cars—almost twice Germany’s per‑vehicle EV rebate. Scaling that ratio to BYD’s 2024 domestic sales yields an implicit subsidy of roughly US$2.6 billion, even before counting local tax holidays and zero‑interest credit lines. In semiconductors, Big Fund III—capitalised at ¥344 billion (US$47.5 billion)—now ropes in six state banks and dozens of “private” investors, ensuring Beijing’s chip strategy survives fiscal tightness.

Implications for Educators and Administrators

Pedagogy must evolve with the evidence. Case studies that depict Huawei or ByteDance as garage start-ups now feel as dated as dial-up; omitting ownership chains and procurement quotas misleads students about the twenty-first-century industrial reality. MBA strategy courses should replace the binary “SOE versus private” typology with a spectrum of effective state control, which includes various degrees of state influence and control over ostensibly private enterprises. At the same time, economics syllabi should consist of modules on subsidy accounting, similar to those on environmental externalities. If we continue to export the old narrative, we will graduate decision-makers unprepared for networked state capitalism.

Administrators likewise require new due diligence templates. A nominally private supplier, majority-funded by a provincial SASAC, may drag export-control liabilities into joint laboratories or dual-use technology licenses. Europe’s October 2023 ex‑officio anti‑subsidy probe into Chinese battery‑electric vehicles, and its July 2025 pledge to intensify Foreign Subsidies Regulation investigations, show how the regulatory tide is turning: research consortia that ignore ownership disclosures could see projects frozen mid‑grant. The prudent university now asks not only “Who owns our partner on paper?” but “Who subsidises them in practice?”

Policy Prescriptions Beyond Tariffs: The Imperative of Transparency and Reciprocity

For policymakers, the first remedy is radical sunlight. Washington’s outbound‑investment screening and Europe’s FSR should converge on a single requirement: any firm seeking market access or public research funds must publish a machine‑readable ownership tree and a five‑year rolling subsidy ledger. Such disclosure would map China’s subsidy web in real-time and provide trade negotiators with a dataset richer than tariff schedules. The USTR’s 2025 agenda already flags hidden subsidies as the next frontier; legislators should turn that recognition into enforceable transparency statutes.

Reciprocity, not escalation, should follow. Under Big Fund III, state banks have pledged ¥114 billion to one chip vehicle; the West cannot out‑spend renminbi for renminbi, but it can deny subsidised incumbents the privilege of European public tenders or US stock listings until they open their markets to genuinely private foreign entrants. Brussels’ early FSR probes—from wind turbines to security scanners—offer a template: calibrated access conditional on verifiable subsidy disclosure, not blanket bans whose costs ricochet through global supply chains.

Anticipating the Pushback

Sceptics claim ownership maps overstate control because Chinese filings are unreliable. Yet the bias runs in the opposite direction. When researchers corrected misclassifications in the Annual Industry Survey, the share of state-connected firms increased from 30% to over 60%. Even lopping a fifth off every linkage leaves a state footprint so wide that the public‑private divide dissolves. Another critique points to Western subsidies—the CHIPS Act, the Inflation Reduction Act—as proof of hypocrisy. But scale and conditionality matter: CHIPS disperses US$52.7 billion over five years, a sum China eclipses annually in its EV sector alone, and it imposes guardrails barring recipients from expanding capacity in China.

The final objection fears academic chill. On the contrary, clear rules enable collaboration by delineating acceptable risk. Universities already comply with export‑control regimes; layering an ownership‑disclosure requirement is bureaucratic, not existential. Transparent criteria protect open inquiry, reassure sceptical legislators, and give genuine private Chinese innovators a chance to prove their independence.

From Statistics to Strategy

The opening statistic—84% state-controlled assets among Chinese Fortune 500 firms—was designed to shock. Let it now guide action. This column has shown that Beijing’s economy operates on a dense lattice of subsidies and equity ties that blur public-private lines, confer material advantages on favored firms, and circumvent tariff-centric tools. Educators must teach ownership networks, administrators must vet them, and policymakers must expose them. The task is not to decouple but to decode—and then demand reciprocity. If we embed that lesson across lecture halls, boardrooms, and trade desks, tomorrow’s leaders will wield sharper instruments than blunt tariffs. They will understand that in dealing with China, the question is no longer “public or private?” but “how deeply wired to the state—and on whose terms?”

The original article was authored by Felipe Benguria and Felipe Saffie. The English version of the article, titled "Beyond tariffs: Chinese state-owned enterprises in the trade war," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.

References

Allen, F., Bai, C.‑E., Hsieh, C.‑T., Song, Z., & Wang, X. (2023). Chinese Corporate Ownership Networks. National Bureau of Economic Research.

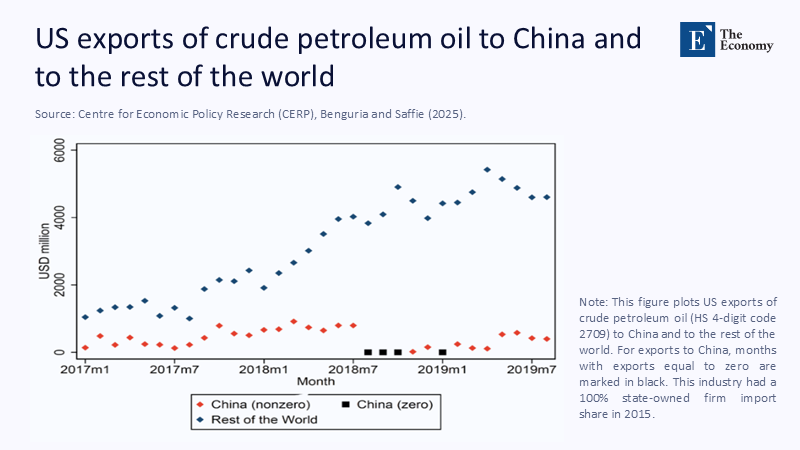

Benguria, F., & Saffie, F. (2025, July 11). Beyond tariffs: Chinese state‑owned enterprises in the trade war. VoxEU/CEPR.

Bloomberg. (2024, May 28). China cashes in banking chips for tech drive.

Carscoops. (2024, June 21). China has invested over $230 billion in the EV industry, a study finds.

Carscoops. (2025, July 14). China’s EV subsidy audit exposes fraudulent claims.

European Commission. (2023, Oct 4). Ex‑officio anti‑subsidy investigation on Chinese BEVs.

Financial Times. (2025, July 14). EU to step up foreign‑subsidy probes, antitrust chief says.

Huawei Technologies. (2025, Mar 31). Annual Report 2024.

IEEE ComSoc Tech Blog. (2024, July 30). Huawei’s rebound driven by government support.

Reuters. (2024, May 28). China cashes in banking chips for tech drive.

Reuters. (2025, Apr 10). China’s subsidies for strategic minerals.

USTR. (2025, Feb 28). 2025 Trade Policy Agenda and 2024 Annual Report.

US Congress. (2022). CHIPS and Science Act.

Comment