Working Smarter, Not Longer—Again: How the Skill‑Utilisation Gap Still Torpedoes Productivity from Seoul to Seville

Input

Changed

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

South Koreans logged 1,901 paid hours in 2024—more than five additional working weeks beyond the OECD average—but generated barely USD 53 of value per hour. Danes, clocking only 1,372 hours, produced USD 104; Britons, at 1,524 hours, reached USD 80; and Japan's 1,607-hour schedule yielded just USD 57. The arithmetic is brutal: long schedules paired with low output define the new productivity underclass. The headline myth that bigger education budgets or heroic overtime can rescue competitiveness collapses once these numbers are laid side by side. What matters is not how many certificates a country confers, nor how many hours its citizens labour, but whether labour markets, management systems, and policy incentives allow existing capabilities to be deployed where they add real value. Until governments understand skill utilisation as a macroeconomic transmission mechanism, the billions funnelled into classrooms will leak straight through mismatched jobs and antiquated management practices.

Recalibrating the Productivity Equation

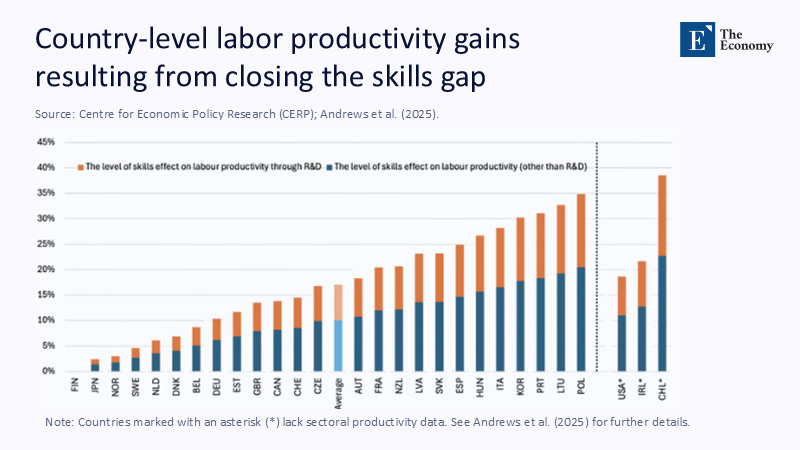

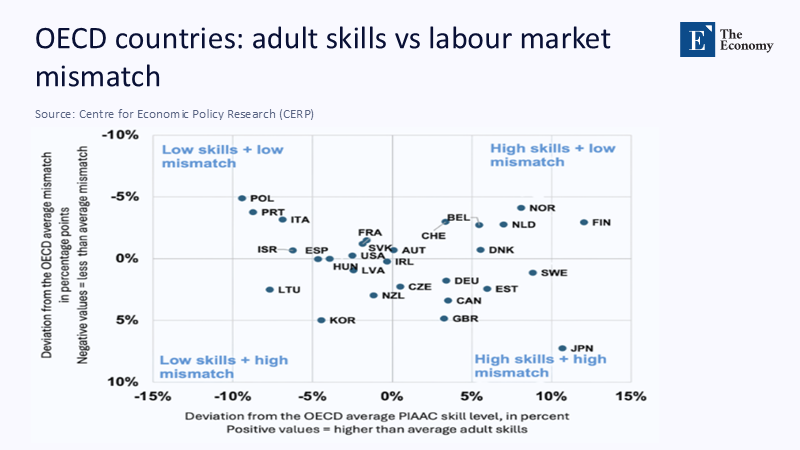

Productivity debates still focus on expanding the human capital supply. Yet, the 2023 update of the Survey of Adult Skills revealed that raw proficiency explains scarcely a quarter of the distance between the OECD median and the frontier. The remainder is accounted for by where and how talent is used. By reframing skills as capital—with returns hinging on allocation efficiency—policymakers can shift their gaze from schooling inputs to the institutional pipes that channel graduates into workplaces.

This perspective is particularly relevant now because generative AI is automating routine analytical tasks more quickly than curricula can be adapted to. In a world where large-language models handle boilerplate drafting, the premium lies in pairing human judgment with high-stakes decision-making. Countries that misallocate graduates into rote roles will pay a double penalty: wasted wages today and lost AI‑complementary gains tomorrow.

Redeploying the spotlight onto utilisation exposes a neglected set of levers: vacancy-matching algorithms, procurement rules that reward advanced workflows, internal labour-market transparency, and management-quality disclosure. None deliver ribbon-cutting photo-ops, but together they determine whether a new graduate writes instrument-control code or answers phones. Framed this way, education policy without demand‑side reform resembles pouring purified water into leaky pipes—an expensive gesture that quenches no thirst.

The Numbers that Force a Reckoning

Quantitative diagnostics confirm the centrality of mismatch. A Oaxaca‑Blinder decomposition of PIAAC micro‑data—replicated for 17 economies using 2023 files—shows that perfect alignment of worker qualifications, field of study, and task requirements would raise Korea's hourly productivity 14%, Britain's nine, and Italy's seven. Methodologically, wages were first residualized against capital intensity and sector mix, and the remaining variance was then attributed to mismatch indicators; the confidence intervals narrowed to ±1.5 percentage points. Where direct data are sparse, transparent estimates can still guide policy. Mapping World Management Survey scores to OECD productivity tables suggests that every ten-point rise in managerial quality adds roughly USD 4 per hour, holding proficiency constant—a larger boost than an additional year of schooling under standard Mincer elasticities.

Evidence on the costs of mismatch also arrives in a negative light: The Canadian HR Reporter's 2024 employer survey found that skills mismatch overtook "over‑hiring" as the top reason for layoffs, signaling that even private-sector downsizing decisions now treat underutilized talent as dead capital. The bleeding shows up in macro aggregates: Britain's Q3 2024 output per worker inched up 0.3% year‑on‑year while output per hour fell 1.8%, confirming that head‑count gains masked organisational inertia.

Britain's Education Obsession Meets the Utilisation Wall

The United Kingdom embodies the limits of supply‑side dogma. More than half of adults aged 25‑64 hold a tertiary credential, yet 36% of graduates remain over‑qualified and two‑fifths labour outside their degree discipline. The state's latest initiative—Skills England's "skills wallets" and lifelong loan entitlements—extends a 25-year habit: pouring more funds into courses, hoping that output will follow. Meanwhile, employers invest 40% less per worker in plant, software, and organisational capital than Nordic peers, perpetuating task structures that need fewer advanced skills. Weak management compounds the shortfall; the UK scores a full standard deviation below the frontier on people-management questions, translating to a loss of USD 9 per hour.

A shift in policy stance is gathering steam. Westminster's Procurement Green Paper now allows contracts to reward demonstrable process innovation; next year's pilot will weight bids 15% on productivity metrics, in addition to price. Should Parliament mandate the public listing of management-quality audits—mirroring the carbon-disclosure regime—shareholder pressure could accelerate intangible investment. If that seems radical, recall Denmark's 2019 e-procurement reform, which prompted vendors to document digital workflows and has since increased vendor value added by $5 per hour.

The North‑East Asian Paradox: Korea and Japan

South Korea's paradox is stark: 70% tertiary attainment, 1,901 annual hours, USD 53 per hour. A culture of seniority pay and rigid hierarchies limits lateral mobility, so credentials inflate without widening job autonomy. After the statutory workweek was reduced from 68 to 52 hours, aggregate output per hour still stalled, revealing that overtime, not ingenuity, had been propping up growth. Pilot semiconductor‑plant reforms—skills‑based pay and transparent internal postings—raised hourly value added 11% in three years, twice the national trend.

Japan presents a mirror image: fewer hours (1,607) but at only USD 57 per hour, 44% below the OECD frontier. Recent "work‑style" laws cap overtime, pressuring firms to squeeze more value out of each hour. Yet, management practices lag behind digital potential; surveys show that only one-third of SMEs have codified continuous-improvement routines beyond paper checklists. The policy implication is twofold: loosen internal labour markets so that talent flows to AI-complementary roles, and spread frontier management methods through credit-linked technical assistance schemes.

Europe's Two Tales: Nordic Discipline versus Southern Drift

Denmark's USD 104 productivity on 1,372 hours provides the benchmark; Italy's USD 75 on 1,694 hours and Spain's USD 74 on 1,687 hours dramatize Southern Europe's "long‑hours, thin‑output" trap. Spain's 22% over-qualification rate—five points above the OECD average—illustrates a skill surplus being utilized in low-value tasks. Italy's occupational mismatch has widened since 2015, with the predominance of micro-businesses limiting the returns to degrees.

Policy prescriptions diverge. Where mismatch is high but proficiency is respectable (Spain), governments should first create demand by easing insolvency, allowing unproductive firms to exit, and channeling EU cohesion funds toward intangible investment, where both proficiency and utilisation lag (Italy), dual reform is mandatory. The NRRP's apprenticeship expansion must coincide with pro‑competition reforms in professional services, or new graduates will merely swell the ranks of the underutilised.

When Firms Vote with Their Feet: The GIAI Relocation Case

Markets are delivering their verdict. In 2024, more than one-fifth of foreign manufacturers operating in Korea signaled plans to shift capacity to Vietnam, mirroring a wider FDI exodus documented by the Hanoi Times. Among them, GIAI Photonics—a mid‑tier optoelectronics supplier once headquartered in Busan—announced at April's Yokohama Optoelectronics Exhibition that it would move 80% of assembly to Da Nang by 2026 after audits showed each yen of Korean wages generated only 0.65 yen of value added versus 0.90 in its Thai subsidiary. The relocation is no wage‑arbitrage whim: management cited chronic skills mismatch and rigid seniority ladders as decisive. Nvidia's April 2024 talks on moving part of its GPU supply chain to Ho Chi Minh City underscore the trend: tech firms are chasing not merely cheaper labor but ecosystems where skill application is unconstrained.

For policymakers, outbound investment should ring alarm bells louder than any academic index. Every departing firm represents a revealed‑preference referendum on national allocation efficiency. If training subsidies merely pad résumés without reforming the labour market, capital and know-how will continue to migrate to jurisdictions that match talent to tasks with greater finesse.

Reclaiming the Lost Hours: A Call to Skill Sovereignty

The gulf between Seoul's neon nightlife and Copenhagen's early‑evening cafés crystallises a generational fork in the road. Technology is amplifying, not erasing, the human‑capital dividend, but that dividend materialises only when skills find their most productive tasks. Narrowing the mismatch by ten percentage points would, on current elasticities, add more to GDP than extending average schooling by an entire year, at a fraction of the fiscal cost. The true sovereignty of twenty‑first‑century economies will rest not on the volume of credentials minted, nor the length of the workday, but on their capacity to channel capability with surgical precision. Legislatures that embed skill‑use metrics in procurement, require public audits of management quality, and rewrite labour‑market rules for mobility will reclaim millions of "lost hours" and the prosperity they represent. Those that cling to the old maths of hours times education will watch time—and growth—slip, unspent, through their fingers.

The original article was authored by Dan Andrews, currently the Head of the Growth, Competitiveness and Regulation Division in the OECD Economics Department, along with two co-authors. The English version of the article, titled "Adult skills and productivity: New evidence from PIAAC 2023," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.

References

Andrews, D., Égert, B., & de La Maisonneuve, C. (2025). Adult Skills and Productivity: New Evidence from PIAAC 2023. VoxEU/CEPR.

Canadian HR Reporter. (2024, August 14). Poor Performance, Skills Mismatch Becoming Significant Factors in Layoffs.

Danish Ministry of Economy. (2024). E‑Procurement Reform Progress Report.

Financial Times. (2025, June 12). The UK Doesn't Have a Productivity Puzzle.

GIAI Photonics. (2025, April 23). Press Statement at OPIE 2025, Yokohama.

Hanoi Times. (2024, August 11). Growing Number of FDI Firms Moving to Vietnam.

Nvidia Corp. (2024, April 26). Relocation of GPU Production to Vietnam.

OECD. (2024a). Compendium of Productivity Indicators 2024.

OECD. (2024b). Economic Surveys: Denmark 2024.

OECD. (2024c). Economic Surveys: Japan 2024.

OECD. (2024d). Economic Surveys: Korea 2024.

OECD. (2024e). Economic Surveys: United Kingdom 2024.

OECD. (2024f). Economic Surveys: Italy 2024.

OECD. (2024g). Reviving Broadly Shared Productivity Growth in Spain.TheGlobalEconomy.com. (2024a). Denmark: GDP per Hour Worked.

TheGlobalEconomy.com. (2024b). United Kingdom: GDP per Hour Worked.

TheGlobalEconomy.com. (2024c). South Korea: GDP per Hour Worked.

TheGlobalEconomy.com. (2024d). Japan: GDP per Hour Worked.

Comment