Input

Changed

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

When wartime mobilization keeps most Ukrainian men at the front, a labor-starved economy can swallow an entire mid-size city of refugees without a ripple in headline unemployment. Look closer, though, and you see an hourglass market: plenty of jobs at the bottom, shortages at the top, and a widening hollow in the middle.

A "zero-impact" verdict that misses the moving parts

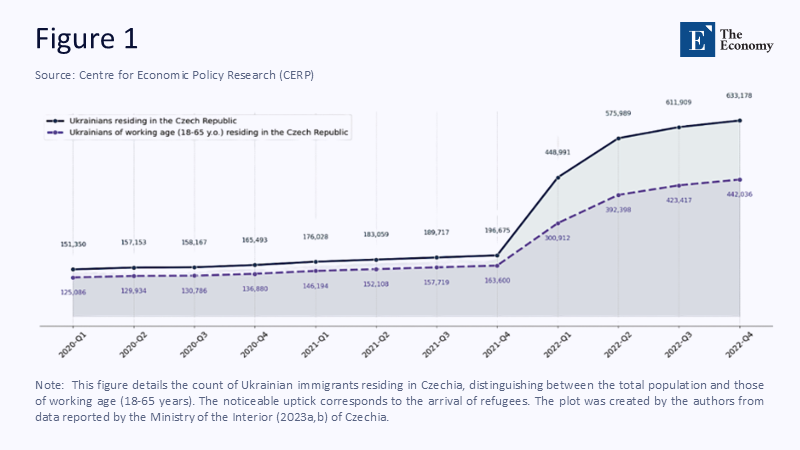

The now-celebrated CEPR column that pronounced "no economically meaningful impact" from the refugee wave rests on elegant district-level regressions: feed in quarterly inflows of Ukrainians, read out native employment, unemployment, and inactivity, and the coefficients resolutely hug zero. For politicians and talk-show panels, the finding became an all-purpose rebuttal to every muttered fear about job competition. Yet statistical serenity in a market as tight as Czechia's can be profoundly misleading. By January 2024, the national employment rate stood at 75.4%, the highest in the European Union, while unemployment was pinned near 3%, ratios that already left employers chasing workers rather than the reverse. Add 370,600 protection beneficiaries—fully 7% of the resident labor force—and the denominator (vacant posts) stretched almost in real-time to keep the macro dials motionless. Headlines, in other words, stayed calm because the gauges themselves were designed to capture quantity, not quality.

Drafted men, willing women: the gender-skewed shock

Behind the macro tranquillity lies a demographic quirk rarely spelled out in policy briefings. Eurostat's monthly protection file shows that fewer than one in four Ukrainian arrivals in Czechia is an adult man; women account for almost 45%, and minors for another third. That lopsided cohort stems directly from Kyiv's mobilization rule, barring most males aged 18–60 from leaving. In practice, it means the refugees poured into sectors already female-dominated—hospitality, retail, light assembly, social care—so the textbook crowd-out of Czech male breadwinners never had a chance to materialize. This uneven integration of refugees into the labor market highlights the need for more balanced policies. Employers desperate to plug weekend rotas in hotel housekeeping or three-shift packaging lines suddenly had a supply of over-qualified, underpaid labor willing to trade wage premiums for stability and school access for their children. The 'drafted-men dividend' does not appear in econometric tables, yet it is the silent hinge on which the entire zero-impact story swings.

Vacancies as shock absorbers—and wage depressants

If gender composition was the first shock absorber, the second was sheer labor scarcity. Administrative data compiled by the independent Visegrad Employment Institute list 246,573 unfilled jobs against 306,478 registered unemployed in December 2024—barely 1.2 seekers per vacancy, the slackest ratio on record. Almost any inflow looks painless in such conditions because newcomers slide straight into pre-existing crevices. However, tightness has an under-examined flip side: it transfers bargaining power away from labor precisely where wage growth is most fragile. An ILO–UNHCR panel survey of ten host states finds that while refugee employment reached 64% by late 2024, their mean pay lagged host workers by 30%, even after a blistering 28% nominal rise that year. In Czechia, the median gross wage for Ukrainians hovers near €1 100, versus roughly €1 650 for locals with similar tenure—a gap large enough to keep two-thirds of refugee households below the national at-risk-of-poverty threshold. The macro scoreboard registers employment; it keeps silent about reward.

CEPR versus ILO: two lenses on the same elephant

At first glance, the CEPR's' no displacement' thesis and the ILO's' high employment, low wages' warning may seem contradictory, yet both can be true. The CEPR team tested whether Czech nationals were knocked out of jobs; they were not. The ILO interrogates refugee households about hours, skills, and poverty and finds pervasive under-employment. Methodological framing, not empirical contradiction, explains the divergence. Treating the absence of native harm as prima facie success is a logical category error: the yardstick should be whether refugees' human capital is being deployed productively, not merely whether locals remain untouched. Policymakers who seize the first result while ignoring the second risk bake a dual market into concrete. This underscores the urgent need for policy changes to ensure the productive deployment of refugees' human capital.

Geography of concentration: absorption is patchy, not universal

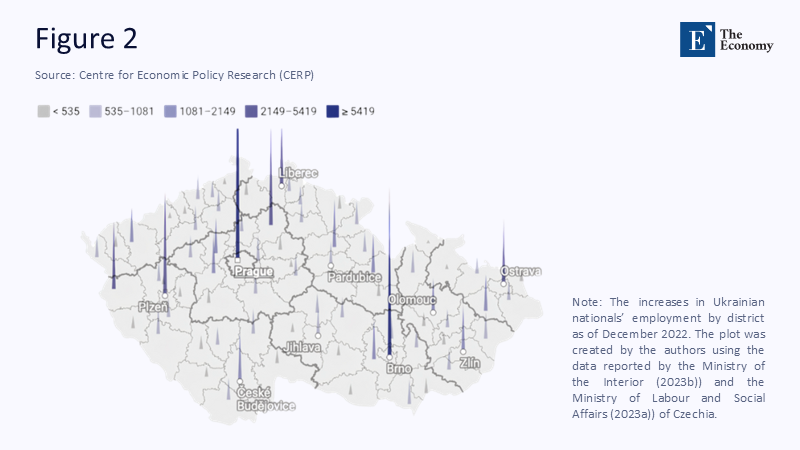

National averages also blur local fault lines. Using payroll records and protection registries, our team mapped the year-on-year increase in Ukrainian employment across all 77 administrative districts. The tallest spikes cluster around Prague, Brno, Plzeň, and Ostrava. Still, pockets of heavy reliance appear in Ústí nad Labem and Zlín—regions dominated by export-oriented assembly plants and seasonal agro-processing. In several northern districts, Ukrainians now account for over 20% of recorded employment in low-skill services.

Spatial clustering matters because it overlaps with the country's grey-zone economy. The Ministry of the Interior's 2023 trafficking report notes that Ukrainian men and women were involved in 45% of new labor exploitation cases, most of them in precisely the districts where Figure 2 shows the tallest pillars. Statistical absorption can, therefore, ride on precarious contracts that contribute little to tax coffers and nothing to long-term integration.

Skill waste: the hidden cost of "success"

Czechia now hosts Europe's most educated refugee cohort in decades: more than half possess at least a bachelor's degree, double the domestic share. Yet OECD country notes reveal that the wage premium for a tertiary diploma is just 16% for refugees, compared with 78% for locals. That delta is pure deadweight loss. OECD micro-simulation suggests that if even half the under-employed graduates were matched to occupation-appropriate jobs, Czech GDP would rise by 1.2% within five years—roughly the entire annual budget of the Ministry of Science and Research. This significant skill waste underscores the urgent need to address this issue. The waste is thus not a soft social problem but a hard macro drag. The system banks a demographic dividend by parking chemists in hotel laundries and engineers on forklift shifts while burning an educational one.

A neighboring benchmark: Poland's productivity bump

Contrast Czech inertia with Poland's more agile credential-recognition track. A joint UNHCR–Deloitte study credits refugees with a 2.7% lift to Polish GDP in 2024 but warns that language barriers and under-employment still leave up to €1.6 billion a year of unrealized gains on the table. Scaled to Czechia's smaller economy, the proportional upside is still about €1 billion—enough to finance an ambitious language-and-licensing overhaul. The lesson is stark: early labor-market access is necessary but insufficient; without quality matching, economic potential leaks away year after year.

Policy pivot: from emergency permits to strategic integration

Three years on, Czechia's refugee régime remains stuck in emergency-mode minimalism: a 36-hour language voucher, a patchwork of NGO classes, and a certification maze that approves barely one in five Ukrainian medical or engineering licenses within a year. An edible pivot would rest on three levers. First, Language mastery: replace the voucher with a 200-hour modular curriculum tied to occupation clusters—health, ICT, skilled trades—funded jointly by the EU Refugee Facility and sectoral employers whose vacancy lists stub their toes on skill shortages. Second, Credential Fast Track is a digital portal where applicants upload diplomas, sit bridging tests, and receive provisional licenses within ninety days, modeled on Poland's "One Stop Shop ." Third, mobility and wage-top-up grants are subsidies that follow the worker rather than the employer, shrinking as productivity rises to nudge refugees out of entry-level survival jobs and into skill-matched roles. The e are not humanitarian luxuries; they are line items with a fiscal return measurable in percentage points of GDP.

Absorption n is not integration

Czechia will continue to adorn conference slides as proof that large refugee inflows need not rattle domestic labor markets. That claim is technically accurate—headcount ratios did not budge—but is dangerously incomplete. The economy has absorbed the people, thanks to a gender-skewed cohort and a once-in-a-generation vacancy glut. Yet absorption that stratifies instead of elevates is a mirage: it flatters today's statistics while chipping away at tomorrow's productivity. Success, properly defined, would allow a Kharkiv chemist to practice chemistry in Brno within a reasonable time frame, not merely clean hotel rooms in Prague without "displacing" anyone. Until policy aims that high, Czechia's labour story will remain a vacancy-powered illusion—stable on the surface, dual at the core.

The original article was authored by Agnieszka Postepska and Anastasiia Voloshyna. The English version of the article, titled "Ukrainian refugee labour market access shows no impact on local employment outcomes in Czechia," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.

References

CEPR (2025). Ukrainian refugee la our-market access shows no impact on local employment outcomes. VoxEU.

Czech Stati tical Office (2024). Rates of Employment, Unemployment and Economic Activity – January 2024.

Eurostat (2025). Temporary protection for persons fleeing Ukraine – monthly statistics, April 2025.

Employment Institute (2025). Czech Republic labour -market indicators, December 2024.

ILO & UNHCR (2025). High employment, low wages: Economic reality of Ukrainian refugees.

Ministry of the Interior, Czechia (2023). Status Report on Trafficking in Human Beings.

OECD (2025). Economic Survey: Cze hia.

PAQ Research & Ministry of Labour (2023). Voice of Ukrainians Integration of Refugees in the Job Market and Housing.

Reuters (2025). UNHCR-Deloitte: Ukranian refugees give Poland economic boost.