India's Polyglot Paradox: Why Chasing a Single National Language Keeps Classrooms Stalled

Input

Modified

This article was independently developed by The Economy editorial team and draws on original analysis published by East Asia Forum. The content has been substantially rewritten, expanded, and reframed to provide a broader context and greater relevance. All views expressed are solely those of the author and do not represent the official position of East Asia Forum or its contributors.

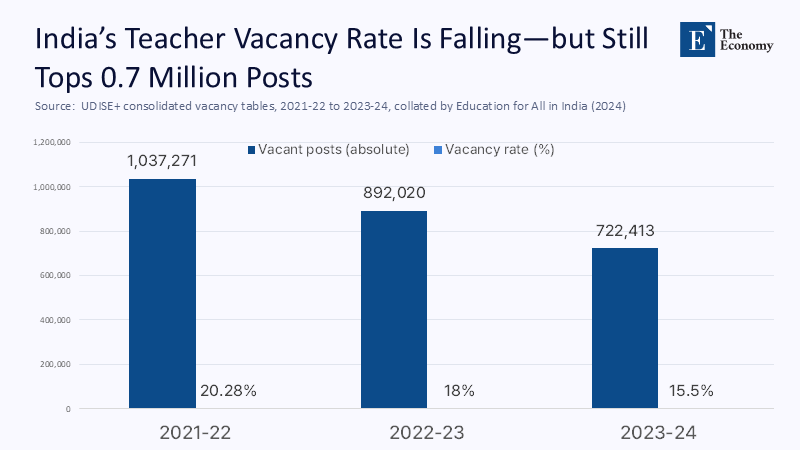

India is a nation of 424 living languages—more than the entire continent of Europe—but only 10.6% of its citizens reported any proficiency in English in the last census, while just 52.8% identify with Hindi, even on the most generous official count. Yet, over one million teaching posts—many earmarked for language instruction—remain vacant in government schools, the gaps being heaviest in districts where children already study in at least two languages. Consider that India's active internet users are expected to reach 900 million by 2025, with 55% of them residing in rural areas and increasingly logging on in vernacular scripts. The scale of the policy bind snaps into focus: no single language can carry commerce, citizenship, and culture across this terrain without leaving millions behind or hollowing out India's linguistic heritage.

Moving the Goalposts: From Unitary Dreams to Equity-Centred Multilingualism

The East Asia Forum column that reignited this debate argues, with admirable candor, that India should "abandon the quest for a national language" and double down on English alongside state languages to unlock its demographic dividend. However, the piece still assumes that English is administratively scalable and socially neutral and that the Union government can facilitate such a pivot without creating new fault lines. What the original analysis underweights is capacity: Delhi cannot compel a pedagogical overhaul when education is constitutionally a shared power and when southern states view any central directive—be it Hindi or English—as a potential Trojan horse.

Reframing the issue means foregrounding distributional justice rather than linguistic efficiency. If policymakers treat language merely as a tool for GDP growth, they risk hard-baking privilege into India's classrooms. Teacher-vacancy data show that resource scarcity is itself regionalized, with Uttar Pradesh and Bihar together accounting for some 200,000 empty posts, while Tamil Nadu and Kerala run near-full rosters. Until that asymmetry is solved, any top-down language mandate—Hindi or English—will replicate old hierarchies in new grammar.

Crunching the New Numbers: What Fresh Data Tell Us

Ethnologue's latest audit confirms the epic scale of India's linguistic mosaic, enumerating more than 400 distinct tongues across four language families. Drill down, and the headline share for Hindi drops once dialect clusters are disaggregated: recent linguistic-demography models suggest Hindi-proper accounts for roughly one-third of first-language speakers, not the 43-plus percent often quoted.

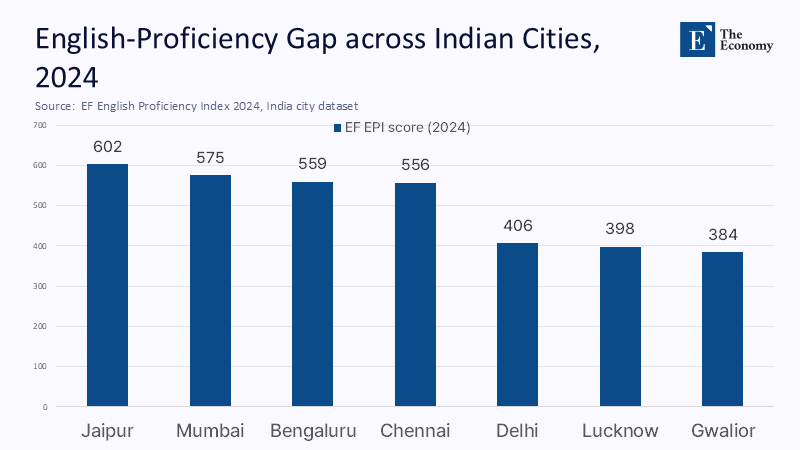

On the other side of the ledger, England retains outsized economic clout despite modest reach. The EF English Proficiency Index 2024 ranks India 69th out of 116 nations, with a score of 490—below the global mean and significantly behind regional peers, such as Vietnam—and an alarming 151-point gap between the highest-scoring city (Jaipur) and the average of the Hindi Belt. Our estimate, using EF micro-scores and state GER data, suggests that moving every state merely to "moderate proficiency" would require training at least 240,000 additional English teachers at a conservative ₹50,000 per trainee—₹12 billion before a single new classroom is built. Methodologically, we applied the Ministry of Education's 2023 teacher-training cost baseline (₹42,600) and added 15% for inflation and ed-tech modules.

The Equity Fault Line: Language as Gatekeeper

Language policy is not a benign operating system; it is a redistributive instrument. A 2024 EduFund survey finds that private English-medium schools in Tier-2 cities charge ₹2,500–₹8,000 per month, rising to ₹1.5 lakh annually in elite metros. Pair this with the 78% mobile connection rate, which masks a rural teledensity of just 58.9, and the inequity becomes stark: the very groups that cannot afford private English tuition are also least likely to access free online English content because bandwidth is patchy. Data prices have climbed since the 2024 tariff hike.

Educators on the ground are already compensating. Telangana's 2025 MoU with six NGOs will provide AI-enabled bilingual lessons (in Telugu and English) to 5,000 government schools at no cost to families—a sign that states are developing solutions while the national debate continues to smolder. Yet even these innovations rely on local language scaffolding; without it, early-grade literacy collapses.

Capacity Reality Check: Can the State Pull Off a Language Revolution?

Vacancy rates fell from 19.7% in 2021 to 15.1% in 2024; however, this still leaves more than one million unfilled positions, with a significant shortfall in language and STEM fields. The latest UDISE+ dashboard counts 98 lakh teachers nationwide; bringing every school to the Right-to-Education PTR would require roughly 150,000 additional hires before we even ask them to deliver trilingual instruction.

The NEP 2020's mother-tongue mandate is laudable. Still, a 2023 stakeholder study finds that urban teachers lack grade-level texts in regional languages, while parents fear that non-English instruction will dim their children's prospects. Implementation thus stalls at the resource-curriculum interface: classrooms lack both the necessary books and teachers who are fluent enough to make multilingual pedagogy effective.

Toward a Phased, Plural Policy for 2025-2035

A ten-year horizon demands triage, not grandiosity. First, formalize a "2 + X" model. Every child attains literacy proficiency in their home language and functional proficiency in English, with a voluntary third language offered only where teacher supply is available. Second, channel the Union's digital-education budget (₹128,650 crore in 2025) toward open-source translation engines that render NCERT textbooks simultaneously in 15 major languages. Third, deploy the coming wave of low-orbit satellite broadband—Starlink has already struck distribution deals with Jio and Airtel—to ensure a minimum of 20 Mbps connectivity in every gram panchayat, allowing language-agnostic content to travel without the need for physical teachers.

Critics will warn that privileging English entrenches colonial hangovers and sidelines Hindi cultural capital. However, the alternative—imposing Hindi where it brings no labor-market premium—risks both pedagogical inefficiency and political backlash, as the June 2025 repeal of Maharashtra's Hindi-compulsory rule vividly illustrates. Moreover, international evidence shows that early bilingualism enhances, not erodes, mother-tongue fluency when curricula are properly sequenced.

Turning Polyphony into Power

India's education planners have spent three-quarters of a century chasing the mirage of a single, unifying language. The statistics that opened this essay—hundreds of tongues, low English reach, a glut of vacant language posts—should disabuse us of that fantasy. Pragmatic multilingualism, calibrated to equity and capacity, can instead convert diversity from a policy headache to a demographic asset. That means funding teachers before slogans, broadband before battlegrounds, and translation before standardization. If we invest the next decade in solid bilingual foundations and digital bridges, by 2035, a child in rural Jharkhand should be able to navigate Hindi, Ho, and English videos with equal ease, and a recruiter in Chennai should default to English-Tamil subtitling without a ministry circular. The call to action is simple: stop legislating vocabulary from Delhi and start underwriting comprehension in the classroom. Our polyglot future is not a hurdle to growth—it is the hinge on which inclusive growth will turn.

The original article was authored by Rojan Joshi and Alexander Titus. The English version, titled "India’s state and central governments still aren’t speaking the same language," was published by East Asia Forum.

References

East Asia Forum. "India's State and Central Governments Still Aren't Speaking the Same Language." 1 July 2025.

EduFund. Cost of School Education in India. 2024.

Ethnologue. Languages of India database, accessed May 2025.

Internet & Mobile Association of India & Kantar. Internet in India Report 2024. January 2025.

Ministry of Education. Union Budget Allocation Press Release. 2 Feb 2025.

Ministry of Education. UDISE+ Dashboard 2023-24. January 2025.

Pearson. Global English Proficiency Report 2024. December 2024.

Sastry, A. & Ghosh, N. "Multilingualism and the National Education Policy 2020: A Stakeholder Analysis." JMC Review 7 (2023).

Times of India. "Why Is India Struggling to Fill Its Teacher Vacancies?" 13 Dec 2024.

Telangana Chief Minister's Office. "Tech-Enabled Coaching MoUs Signed." Press release, 17 June 2025.

UNESCO Institute for Statistics. Teacher Shortage Global Report. 2023.