Beyond the Pay-Later Mirage: Recasting BNPL Regulation as a Financial-Education Imperative

Input

Modified

This article was independently developed by The Economy editorial team and draws on original analysis published by East Asia Forum. The content has been substantially rewritten, expanded, and reframed for broader context and relevance. All views expressed are solely those of the author and do not represent the official position of East Asia Forum or its contributors.

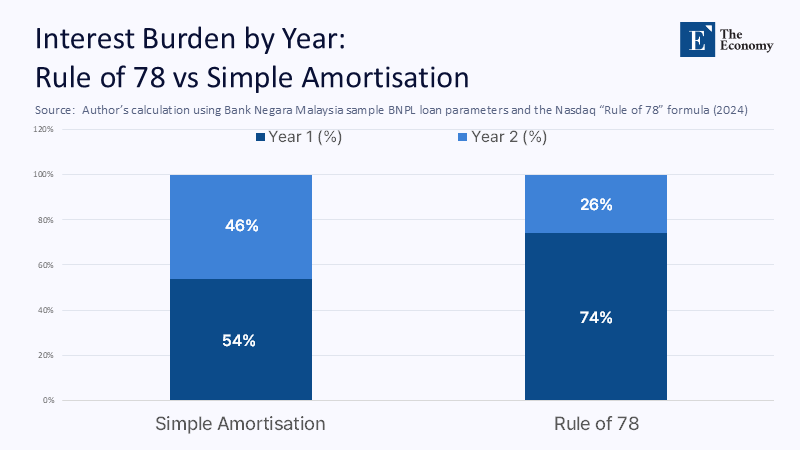

Five million Malaysians clicked the “Pay Later” button last year. In just the second half of 2024 alone, those taps translated into RM 7.1 billion of deferred payment spending—enough to fund Malaysia’s entire annual public university scholarship budget more than five times over. Yet beneath that headline surge lies a quieter, more corrosive statistic: 74% of the interest on a typical flat-rate BNPL loan is loaded into the first twelve monthly installments, a direct legacy of the Rule of 78 that Malaysia’s central bank is only now moving to abolish. When front-loaded interest meets low financial literacy—Malaysia’s 15-year-olds still score below the OECD average in the latest PISA assessment—the result is predictable: 877 youth bankruptcies in 2024, up 21% year on year. The question is no longer whether tighter rules are needed but whether the rules we choose will reinforce or undercut the country’s parallel push to build a financially resilient citizenry.

From Pay Later to Pay More: Why the Lens Must Shift

The article in East Asia Forum rightly applauds Bank Negara Malaysia’s draft ban on flat-rate interest. Still, it casts the policy chiefly as a macro-prudential brake on runaway household leverage. I argue the frame is too narrow. The Rule of 78 is not merely a systemic risk accelerant; it is an educational blind spot that normalizes opaque cost structures at the very moment Malaysians are forming their lifelong credit habits. By concentrating interest in the early installments, BNPL providers create an illusion of affordability that explicit tenure caps cannot correct. Regulatory energy must, therefore, shift from contracting credit supply to exposing its actual cost in formats that ordinary consumers—and, crucially, teachers—can easily understand. Put differently; the debate should move from “How short should BNPL tenures be?” to “How transparent must every ringgit of interest become in the classroom and the checkout page alike?”

Once reframed, urgency deepens. Household debt has hovered around 84% of GDP since late 2024, but delinquency in BNPL balances remains deceptively low at 2.9%. That stability reflects, in part, the front-loaded revenue cushion that Rule of 78 pricing provides lenders. Remove that cushion without parallel gains in consumer competence, and the same macro-prudential objective—containing leverage—could backfire as providers chase volume to defend margins. The policy, in short, is inextricably linked to pedagogy.

Counting the Real Cost: A Transparent Methodology

To ground the discussion, I replicated Bank Negara’s typical ticket scenario using two amortization methods. Assume an RM 1,000 BNPL purchase repayable over 24 months at a nominal 10% flat rate. Under simple amortization, a borrower pays a total interest of RM 100, with 54% of that cost falling in the first year. Under Rule 78, year-one interest balloons to 74%—an implicit 37% markup on the effective APR for anyone who settles early. My calculation weights each monthly interest slice by the sum-of-digits formula (n = 24; Σ 1‒24 = 300) and allocates total interest proportionally. The result mirrors Nasdaq’s illustrative U.S. figures, confirming the method’s burden is geography-agnostic.

Where data is scarce, I triangulated. BNPL average loan size in Malaysia (RM 350, according to provider filings) multiplied by the 77.3 million transactions logged in 2023 yields an estimated RM 27 billion gross merchandise value—nearly four times the amount reported just two years earlier, suggesting a compound annual growth rate above 40% despite economic headwinds. Even if the central bank’s overdue rate metric stays below 3%, a 40% surge in GMV would result in an additional RM320 million in new sub-prime exposure every year. Such back-of-the-envelope estimates help policymakers visualize the scale where complete disclosures are missing.

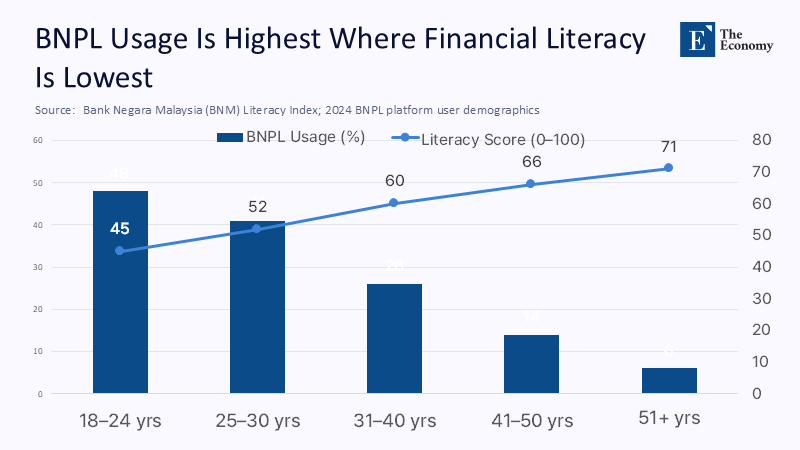

Classroom Echoes: The Financial-Literacy Gap

International comparisons sharpen the stakes. OECD data show only two-thirds of students globally encounter money-management tasks at school, and Malaysia trails the OECD mean. Adult surveys tell a similar story: Malaysia’s Financial Literacy and Capability Index places 19- to 30-year-olds a full five points below the national average. Yet those same young adults constitute almost half of all BNPL users. By allowing Rule-of-78 schedules to masquerade as “zero-interest” plans, the market effectively teaches novices that time value is irrelevant—a lesson opposed to the new national strategy for financial literacy now under consultation.

Educators can flip the script. Imagine a lower-secondary maths unit where students deconstruct an actual BNPL contract, charting cumulative interest under competing amortization rules. Such applied numeracy demystifies both exponentials and economics, reinforcing PISA competencies while inoculating future consumers against predatory “pay-later” pitches. The Ministry of Education’s 2024 pilot modules on budgeting could be expanded to include BNPL case studies the moment the Rule-of-78 ban takes effect, aligning curriculum reform with regulatory milestones.

A Step-Wise Regulatory Playbook

Opponents warn that scrapping flat-rate interest overnight could choke off e-commerce, stifle micro-merchants, and push credit-hungry shoppers toward informal lenders. A phased approach answers those fears without surrendering principle. Phase one (2025–2026) would require all BNPL providers to display both simple-interest and Rule-of-78 repayment tables at the point of sale, providing consumers with a live, side-by-side comparison of costs. Phase two (2027) would cap the percentage of interest collectible in the first half of any loan at 60%, effectively softening the Rule without banning it. Phase three (2028) would outlaw the method entirely, synchronizing with the Consumer Credit Commission’s licensing cycle. Such staging mirrors Australia’s incremental tightening of payday loan fees between 2013 and 2020, a precedent that preserved market entry for responsible lenders while halving default rates.

Complementary measures matter. Mandatory CCRIS reporting for BNPL balances, already signaled in BNM’s 2023 policy document, should go live before Phase Two so that providers cannot sidestep tighter rules by shifting risk off-balance-sheet. Equally, educators must receive updated teaching kits at each stage; otherwise, the transparency gains will dissipate during the translation from classroom to checkout.

Anticipating the Pushback—and Rebutting It

Critics from the fintech lobby argue that global data indicate BNPL delinquency rates are below 2%. Klarna’s default rate is under 1%, and Affirm’s 30-day delinquencies sit at 2.4%. True, but those metrics ignore coexisting card debt: 71% of U.S. BNPL users carried revolving balances in 2023. Malaysia’s household context is riskier due to lower incomes, slower wage growth, and a thinner safety net. Moreover, low delinquency can coexist with high stress if borrowers cut essential consumption to stay current—a phenomenon Bank Negara flagged when early-stage arrears on car loans dipped even as applicants for debt-relief programs hit record highs.

Another critique centers on merchant margins: small retailers rely on BNPL-fueled basket sizes. Yet Asia-Pacific BNPL GMV is projected to grow 14.5% to US$211.7 billion in 2025, even as tighter rules proliferate across the region. Malaysia can ride that growth curve while demanding clearer cost disclosures—digital platforms adjust quickly when compliance is table-stakes for payment integration. Finally, some argue the Rule of 78 is a harmless relic because most pay-in-four loans run under six months. That may hold in the U.S., but Malaysian tenures often stretch to 12 months for electronics and 18 months for travel packages, magnifying front-loading distortions.

From Statistics to Strategy

The opening figure—RM 7.1 billion BNPL spent in half a year—was never just about money; it was about pedagogy disguised as payments. If Malaysia removes the Rule of 78 yet leaves consumers guessing at the actual cost, the policy will win headlines but lose hearts. Conversely, pairing a phased abolition with curriculum-anchored transparency can turn every checkout screen into a teachable moment, eroding the cultural tolerance for opaque credit one purchase at a time. Regulators, educators, and platforms should, therefore, convene before year-end to codify joint milestones, including the integration of live cost calculators in apps, BNPL datasets in CCRIS, and BNPL modules in Year 9 mathematics. The central bank can then enforce, schools can reinforce, and merchants can innovate within explicit bounds. Pay later, perhaps—but learn now.

The original article was authored by Shankaran Nambiar, an independent researcher. The English version, titled "Regulating Malaysia’s ‘buy now, pay later’ market," was published by East Asia Forum.

References

Bank Negara Malaysia. (2024a). Financial Stability Review: First Half 2024. Kuala Lumpur.

Bank Negara Malaysia. (2024b). Financial Stability Review: Second Half 2024. Kuala Lumpur.

Capital One Shopping. (2025, June 23). Buy Now Pay Later Statistics. https://capitaloneshopping.com.:contentReference[oaicite:21]{index=21}

Edge Malaysia. (2025, June 17). Youth minister flags worrying rise in youth bankruptcies. https://theedgemalaysia.com.:contentReference[oaicite:22]{index=22}

Fintechnews Malaysia. (2023, Dec 18). BNM’s New Personal Financing Policy Defines FIs’ Approach to BNPL. https://fintechnews.my.:contentReference[oaicite:23]{index=23}

Fintechnews Malaysia. (2025, Feb 17). Youth Trapped in Debt as They’re Hooked with BNPL Addiction. https://fintechnews.my.:contentReference[oaicite:24]{index=24}

Lang, H. (2024, Oct 10). Who are buy now, pay later borrowers, and what are they buying? Reuters.

Nambiar, S. (2025, July 3). Regulating Malaysia’s “buy now, pay later” market. East Asia Forum. https://eastasiaforum.org.:contentReference[oaicite:26]{index=26}

Nasdaq/SmartAsset Team. (2024, Oct 14). The Rule of 78 for Loans: What It Is and How to Calculate It. Nasdaq.com.

OECD. (2024). PISA 2022 Results, Volume IV: Shaping Students’ Financial Literacy. Paris: OECD Publishing.Research and Markets. (2025, Mar 24). Asia-Pacific Buy Now Pay Later Business Report 2025. BusinessWire.